|

From Hardscrabble to Euclid

Paper written for the Fortnightly Club, Redlands, California

November 6 , 1969

Frank M. Toothaker

Summary

Grinding environments tend to crush youth’s hope for recognition and success. The poverty and scant opportunity of Edwin Markham’s first fifteen years cramped his development, but an inspired teacher in three short months fired his inborn hunger for knowledge, especially of the poets and philosophers of the world. In spite of all handicaps Markham won a college education, and immediately made it a tool for his educator’s career.

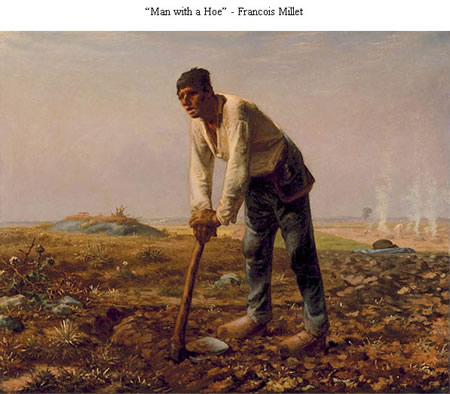

He grew increasingly sensitive to nature and to man. Especially was he moved by the inexplicable puzzle of why some ride high and others are ground down. After seeing Millet’s painting, “The Man with a Hoe”, he burst into poetic challenge to any system that degrades any worker. He foresaw the upheaval of world peasantry, perhaps exampled by Russian and Chinese masses. He may help late 20th century citizens to understand some of the tensions that erupt in current revolts against vested interests, power control and the authority of an elite.

Because he sensed that Lincoln was a kindred spirit, that of a leader up from the soil, he wrote of him as one aware of the worth of man as man. His poem, “Lincoln, Man of the People” is inscribed on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Hodgenville, Kentucky.

Out of the wide ranges of his poetry, perhaps none is better known than his quatrain, “Outwitted”, a faith that the society in which mankind accepts oneness is the society creative and enduring.

From Hardscrabble to Euclid

A PAPER presented to the Fortnightly Club of Redlands,

by Frank M. Toothaker

November 6, 1969

Honore Willsie Morrow in her novel, “We Must Travel” revives the glory and tragedy of Marcus Whitman. In 1836 he accomplished what no man before had done – make it by wagon to Oregon. Seven years later he led a wagon train on “The Great Migration” from Independence, Missouri, to Fort Laramie, to Fort Hall and to Oregon City, Oregon. Cholera, small-pox, Indian hostility, raging rivers and landslides had struck with pitiless suffering and death. Decaying gravestones and carvings in soft rock tell their tale of the price they paid for a determined courage.

From Michigan and Illinois another wagon train gathered for the journey, its captain, one Samuel Markham, a direct descendent of the William Penn family. With his wife, the former Elizabeth Winchell, Markham prodded his oxen until they arrived at Oregon City. Elizabeth became the first published writer in the territory. Samuel began raising apples, and together they added to their family, first a girl and a boy. In 1852 their last child was born and they named him Charles Edwin. Somehow the Charles got lost. Within a few years Samuel died and Elizabeth with the children migrated to California. She found a ranch among the hills of Solano County, then called Laguna Valley. Wheat raising took grinding labor, and the results offered meager reward. Edwin worked as a shepherd and bronco-buster. The winter season offered three months’ school, and he managed to attend. Thus by the time he turned fifteen he had accumulated one full year of elementary education. During one of these three-month terms he came under the magic spell of one of those rarities, a dynamic, magnetic teacher. Edwin felt something awaken in him. Of this teacher he later wrote: “He made me a lifelong reader and writer of poetry”. This man listened intently to the lad’s storied descriptions, and in turn he lighted the youth’s imagination and fired in him an irresistible thirst for learning – to know, to feel and to try to tell the majesties of mountains or of men. Books, Edwin had to have books. With this teacher he had touched them. Compellingly he felt he must know the thinkers of the world, especially the thinkers who could catch the music of language and pour it forth in poetry. He asked his mother to help him get the works of Bryant, Thomas Moore, Byron and Tennyson, plus a dictionary. Somewhat sarcastically she exploded: “And where, boy, are you going to get the money?” “From you, mother”, he confidently replied. “Oh, no, I have no money for books. There’s hardly enough for bread.”

Full of the maturity of fifteen, with one year’s schooling, yet determined to get a college education, he saw that he would have to be his own money-getter. A neighbor who owned twenty acres of the rockiest, stumpiest land suggested, “I’ll give you twenty dollars if you plow that field for me”. Edwin took the job. It might mean books. For three weeks he dodged stumps and suffered being thrown up on the plow handles by collisions with buried rocks. He took the twenty dollar gold piece, his wages to his mother. She could believe he really wanted the books, and they were secured. To this meager library were added a few old volumes found in an abandoned cupboard. A Mr. Powers, editor of the Solano “Republican” gave him the outdated exchanges. He devoured them all.

Now again he appealed to his mother to send him to Vacaville where there was a college – well, almost anything was a college in the 1867 west. He was greeted by that adamant “No.” He now despaired of any softening of that refusal. He contemplated suicide, but discarded the idea. Run away? Yes, he could to that. He owned a horse and saddle. Secretly he packed a skillet, a half sack of flour, some bread – and, you guessed it, a couple of books, tying the bundle to his saddle. He took off, as he said, in the direction which he knew least. He had not gone far until a youth friend, John Huckins joined him to ride the one horse. Living on fish, berries and birds they made their way to Clear Lake. Here John picked up a horse, about which ask no questions. Their escape route took them toward the Round Valley Indian settlement. (Once again Round Valley and its Indians hit the news) They slogged up to the Eel River in a blinding rainstorm, and the river interposed a raging flood. They tied themselves to their horses, and but for that they would have drowned. Their animals managed to struggle across and for the night the boys found shelter under a giant sequoia log. At the Indian reservation they were greeted with hospitality flavored with suspicion. Could these boys be horse thieves? The Indians were 50% right! They overlooked their suspicions, but two voracious appetites prompted their willingness to urge the travelers on. They turned south toward Sacramento Valley. Coveys of grouse helped fill their pot. They were met and for a time held by a suspicious posse. John Huckins took to his heels. Edwin found a job with a farmer, but suspected of being a highwayman, he decided to work his way toward Colusa where he found no better employment than to keep cattle from invading a rancher’s wheat fields. Perhaps a tinge of homesickness, or of disillusionment with running away, prompted him to write to his sister Louisa. His frantic mother wrote under the date of July 25th, 1867 to say: “Everything, even the cows want to see you. If ever I was cross to you I am punished enough”. Edwin didn’t believe it, so he stayed on, working through harvest. When the grain had been gathered the job ended, and most of the men could not remain. One of them, an unusually large, muscular fellow offered Edwin an unusual proposition. He said, “Young fellow, I’ve been watching you. You’ll do. I stop stages. I need a fellow to help me, to hold a shotgun on the driver, and you are the bird for the business.” Now here lay a delicate bit of diplomacy. He was no match for the highwayman, whom some think may have been the celebrated Black Bart. Surprisingly, this teenager sensed the delicacy required, handled it carefully, and succeeded in freeing himself from further consideration as a hold-up man’s accomplice.

His mother now knew where to find him, and with his brother, John, she hitched up to the spring wagon and drove to get him. He tethered his horse behind the wagon, got in, and without comment rode home with them. What a fifteenth year in a boy’s life! He had declared his independence, he had maintained his integrity, he came home without any commitment to give up his quest for an education. Hardscrabble had not beaten him down. Indeed, hardscrabble sent him on the search for soaproot, a substitute for home made lye-grease soap. Grease, in hardscrabble, is food; soapweed a passable substitute. It lathered. He found some growing under the edge of a large rock. To his amazement his digging tool struck metal which proved to be a rusty can. When he broke it open it poured out five, ten and twenty dollar gold pieces, $900 worth. That became his scholarship fund at San Jose State Normal school, and there he graduated in 1872, aged twenty years.

No matter what sort of a certificate he received in San Jose, on its authority he immediately sought for a school to teach, and in the Mother Lode country he found one. It had no roof, no walls, and no furniture. Around an oak tree he erected a picket fence, and this he called “my citadel of learning.” He hand tooled the parts of ten tables and put them together, one for himself and one each for nine pupils. Too youthful yet to cast a ballot, but a man now dedicated to teaching frontier youth. In a few years he won a degree from the college then centered in Santa Rosa, and within a few more years he had distinguished himself enough to be entrusted with the principalship of the Oakland Teachers’ Training School. He had come a long way from literary poverty. He once listed his family’s library: “We had only the Bible, the story of the Pyramids and their relation to Scripture, and a copy of the Almanac. We were poor people”. Hardscrabble had infiltrated his blood from birth to young adulthood.

To all of life, of mountains and rivers, of trees and wild life, and even more, of men and the ways of men, Markham had recognized an increasing sensitivity. Inevitably he would meet the moment when he would pour out some of his soul’s concern and appreciation about them. In 1880 when he could boast of being 28 years of age he broke into print with a poem, “The Gulf of Night”. Another twenty years would pass before his pen became prolific.

Three determinative experiences had melded into his character. He had felt the leap of inspiration through a dynamic teacher; he had discarded temptation to parasitism as a highwayman; he had accepted the power of gold to further his quest for learning but had denied its power over him. Now he was thrilling to throw open the windows and doors of wisdom for the youth of American public schools. The boundless artistry of God in nature had ingrained itself in his appreciative spirit. Now he was to be inoculated with a growing, living concern for all of the human family. Through a small print he became aware of a simple, impecunious French painter, Francois Millet. He would have felt a kinship with Millet under any circumstances, for the latter lived close to the soil of common humanity. Back of Millet’s “The Gleaners” lay a thrift born of poverty unto hunger. Faith and devotion to God, and gratitude for the day spoke with soft but eloquent voice from “The Angelus”. The small Millet print he had found cried out with a different voice. It faced Markham with a fellow man in whose soul hope had shriveled, and for whom the future held only the promise of an aching back even down to the grave. Markham said: “It at once struck my heart and my imagination. For years I kept the print “The Man with a Hoe” upon my wall and the pain of it in my heart”. He wrote four lines about it, and filed them away. His headship of the Teachers’ Training School engrossed him while thirteen years came and went.

The nineteenth century slowly drew toward its close. Some event took Markham to the home of the San Francisco banker, William H. Crocker, and there hung the original Millet, “Man with a Hoe”. Its pathos and its latent threat hypnotized him. It riveted him to the spot. No casual glance sufficed. Listen to his account of what happened. “For an hour I sat enthralled in front of it, and when I left I was like one under a strange enchantment. It was as though this awe-inspiring shape, full of terror and mournful grandeur, had risen before me from Dante’s dark abyss; yet at the same moment I was filled with exaltation as though the heavens had opened and given us a message for mankind.” May I project it for us to see, and as I do, grant me the privilege and your patience while I read the lines characterized by Who’s Who as “The battle cry of the next thousand years”.

“Bowed with the weight of centuries, he leans

Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground,

The emptiness of ages in his face,

And on his back the burden of the world.

Who made him dead to rapture and despair,

A thing that grieves not and that never hopes,

Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox?

Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw?

Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow?

Whose breath blew out the light within this brain?

Is this the Thing the Lord God made and gave

To have dominion over the sea and land;

To trace the stars and search the heavens for power;

To feel the passion of Eternity?

Is this the Dream He dreamed who shaped the suns

And pillared the blue firmament with the light?

Down all the stretch of Hell to its last gulf,

There is no shape more terrible than this –

More tongued with censure of the world’s blind greed –

More filled with signs and portents for the soul –

More fraught with menace to the universe.

What gulfs between him and the seraphim!

Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him

Are Plato and the swing of Pleiades?

What the long reaches of the peaks of song,

The rift of dawn, the reddening of the rose?

Through this dread shape the suffering ages look;

Time’s tragedy is in that aching stoop;

Through this dread shape humanity betrayed,

Plundered, profaned, and disinherited,

Cries protest to the Judges of the World,

A protest that is also prophesy.

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

Is this the handiwork you give to God,

This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quenched?

How will you ever straighten up this shape;

Touch it again with immortality;

Give back the upward looking and the light;

Rebuild in it the music and the dream;

Make right the immemorial infamies,

Perfidious wrongs, immedicable woes?

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

How will the Future reckon with the Man?

How answer his brute questions in that hour

When whirlwinds of rebellion shake the world?

How will it be with kingdoms and with kings –

With those who shaped him to the thing he is –

When this dumb Terror shall reply to God

After the silence of the centuries?”

The author’s copy came into the hands of the San Francisco “Examiner”, to be released for publication only after a perfectionist’s attempt at just the right punctuation. At last, in 1899 the newspaper featured the poem in a special printing, its border illuminated with a hand decoration of tiger lilies. As though a lightning strike had ripped the world its people were cloven into two camps. One camp received the word as though an Amos or a St. Paul had prophesied, breaking the silence of the centuries. The other camp heard this trumpet challenge as a threat to their comfortable, complacent, insulated world. Collis P. Huntington, railroad magnate, offered a prize to anyone who could give the coup de grace to Markham’s philosophy. Whether they were stirred to action by antagonism to the Hoeman doctrine, or by the hope of winning the prize, writers numbering over five thousand replied from all over the world. John Vance Cheney, a contemporary of Markham, won the competition. The gist of his literary rebuttal is caught in these lines:

“Need was, need is, and need will ever be,

For him, and such as he;

Cast for the gap, with gnarled arm and limb

The mother moulded him.”

Markham wrote to Cheney: “Your reply is good poetry, but bad philosophy. You declare … the Almighty created the Hoeman to drudge and slave for us.”

Many other criticisms flooded in. Some garden lovers were unhappy with the poem, remembering some joy in digging and delving in the soil. Markham wrote: “Not every man with a hoe. Thoreau hoed his bean field, his hoe tinkling against the stones made music.” Some farmers felt they suffered an uncalled-for slight. The poet answered: “I did not say the poem was written after seeing the American farmer riding rosily on his reaper.” Markham spoke for himself, a farmer: “The smack of the soil and the whir of the forge are in my blood … I know the fight against the death clutch reaching to take the home when crops have failed or prices fallen”. He stood his ground, the poem must not be judged apart from Millet’s interpretation of “The Man with a Hoe.” With Job, Markham pondered “why are some men to be ground and broken?”

Perhaps the most widespread attacks on “The Man with a Hoe” came from Labor (capital L). Markham withheld comment until some thousands of critics had spoken or written. Then he expressed himself, “having read for twelve months what these critics say I meant to say in the poem, it seems to me that I may be allowed to express my own opinion on this and kindred matters”. He recited his own familiarity with hard work, endless tedium and cruel loss. “I know the dull sense of hopelessness that beats upon the heart in that monotonous drudgery that leads nowhere, that has no light ahead”. He really knew! Then he sought to emphasize in prose what he had tried to say in sublime poetry.

“Millet puts before us no chance toiler. No, this stunned and stolid peasant is the type of industrial oppression in all lands … He might be a man with a needle in a New York sweatshop, a man with a pick in a West Virginia coal mine … The hoeman is the symbol of betrayed humanity. In the hoeman we see the slow, sure, awful degradation of man through endless, hopeless, joyless labor. Did I say “Labor”? No, drudgery … Do I need to say that the hoe poem is not a protest against labor? No, it is my soul’s word against the degradation of labor, the oppression of man by man … I was forced to utter the awe and grief of my spirit for the ruined majesty of this son of God.” One would not really need an index to surmise that Markham summed it all up in four lines entitled:

“The Third Wonder”

“Two things”, said Kant, “fill me with breathless awe:

The starry heaven and the moral law”.

I know a thing more awful and obscure –

The long, long patience of the plundered poor.”

One can hardly be surprised that this theme, so startlingly, dramatically, even shockingly spelled out quickly found itself broadcast in forty languages, and that it was reprinted in current literature twelve thousand times. Four thousand parodies appeared, so I am told, but I found none in our library. David Starr Jordan lectured on it two hundred times. Louis Untermeyer called Markham “a blurred composite of four Hebrew prophets, and all of the New England poets.” Financially, for all this effort, sensitive spirit and continuing concern Markham received $40.00. He has a secure place among the greatest of American pioneers who have contended for social justice.

Markham, the nine year old boy, lived far from where cannon poured their deadly fire into Fort Sumter, initiating a bloody contest between people whose economic interest and social status rested on black slavery and people who, partly for belief in human freedom, partly because their economy involved commerce and machine industry, and partly because they determined to thwart the dissolution of the American Union. At the core of the fratricidal hurricane of emotion moved a weary, determined, sane man, Abraham Lincoln. How much the juvenile Markham knew of Lincoln is hidden from us, but when Old Abe’s first twentieth century birthday celebration drew near Markham set down his pride and appreciation in the poem: “Lincoln, Man of the People”. It was acclaimed and made a feature of this celebration. It rang so true to the spirit of the Liberator that it was elected to be inscribed on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial at Hodgenville, Kentucky. When Washington, D.C. raised its beautiful tribute to Lincoln, this poem and its author were called upon to share the dedication. “Lincoln”, Markham said, “joined the men who are willing to suffer for a great cause, the men who are willing to take unprofitable risks for unpopular truths.” In the railsplitter he recognized a fellow citizen who stood tall amid Hardscrabble.

In Lincoln’s magnanimous attitude toward those whose thought and action had ruined the economy of the South, and whose belligerence doomed so many to die, Markham saw one of the marks of a great man. “Jefferson Davis ought to be hanged” was shouted by the mob, and even by Lincoln’s associates. “We’ll hang Jeff Davis from the sour apple tree” sang the post-war ditty. Not so, thought Lincoln, who responded: “Judge not that ye be not judged”. He met with his Cabinet, saying among many things: “There is too much desire on the part of our very good friends to be masters, to interfere with and dictate to these States, to treat the people not as fellow citizens; there is too little respect for their rights”.

At this point Markham noted that Lincoln came out of Hardscrabble and began to adopt Euclid. Markham gathered up this conviction and crystallized it into four lines. Into this crystal he put the Beatitudes, boiled down to their essence. He added the secret of St. Paul’s essay on Love, as found in his letter to the far-from-perfect people of Corinth. He inoculated it with some of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural and from the Gettysburg Address. Just four lines, but their brevity reminds one of the First and Great Commandment and its corollary, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself”. Those who are characterized by Kipling as “heathen hearts that put their trust in reeking tube and iron shard” have beaten upon the spirit of this quatrain, but in every age it is reborn. This philosophy challenges the Berlin Wall. It will infiltrate the Bamboo Curtain, not tomorrow, but slowly as the mounting of the tide. It overrides embargoes and reveals the indecency of such prejudices as have hounded Jews, and blacks, and immigrants and many another minority. It pierces the awful but pitiful clan prides that break forth in “Deutchland ueber Alles”, or “Brittania Rules the Waves” or even “America First”. These pratings sound like tribal drummings. They fall far short of spelling out the sterling quality of enduring patriotism, of love of country.

In Markham’s quatrain there speaks the still small voice that alone has power to keep open a road to a decent future for this world. To ears dulled by sonic booms these quiet words may scarce be heard, and if heard above the din of modern busyness, may be tossed off as empty idealism. But, in a shrinking human habitation, now recognized by us all, this world view holds promise for our children and their children.

Of Markham, his neighbor, Joaquin Miller speaks understandingly: “His it is to speak whether men will hear, or whether they will forbear.” And Herbert Hoover added: “We need something to raise our eyes above the immediate horizon”. So Markham seized upon a geometric design from Euclid and entitled it:

“Outwitted”

“He drew a circle that shut me out,

Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took him in!”

Partial Bibliography

Markham: “Man with a Hoe” and other poems -- 811. M 341 m

Untermeyer: “Modern American Poetry”, pp 108-111 811.08 Un 8 m 5

Goldstein, Jess Sidney: “Escapade of a Poet”, Pacific Historical Review, 13, No. 3,

Sept. 1944, University of California Press

Sullivan, Mark: “America Finding Herself”, p. 236 ff. “Our Times”

Downey, David G. : “Modern Poets and Christian Teaching”

Stidger, Wm. L: “Edwin Markham”

Fitch, G.H. : “Great Spiritual Writers of America” p 136 ff. Bookman 9:441

Current Biography, 1940 – “Markham”

Library Journal, June 15, 1942, p 576

Sullivan, Mark: “The History of our Time”, in Songs and Stories of California

“The Strange Story of the Hoe Poem” p. 270

Independent Magazine, January, February and April, 1900. October 1916

Bookman: May 1908, June 1915

Overland magazine, new series, October 1915

Delineator: August 1909

Literary Digest, 60:32 January 18, 1919

Cosmopolitan – 41:480, p 567 ff. 42:20-8

Saturday Review of Literature, 8:685, Apr 23, 1932

Christian Century, 50:723, May 31, 1933

The author’s résumé of formal education:

Frank M. Toothaker

University of Southern California, Bachelor of Arts, Sociology major under

Dr. Emory Stephen Bogardus.

Drew Theological Seminary, Bachelor of Divinity, 1918

Columbia University, courses in Educational Sociology and Philosophy 1917

Pacific School of Religion, Doctor of Divinity, 1948

|