4:00 P.M.

by Richard N. Moersch M.D.

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public

Library

The decision of a men's discussion

society meeting in London in 1788 to promote the investigation and exploration of West

Africa was principally one of intellectual curiosity on the part of the members. over the

next forty years however, it led to the opening of this enormous and hidden area of the

world as well as setting the foundation for the commercial and military domination of this

part of Africa by the British and French empires. This was accomplished at little cost to

the involved governments but at a terrible price paid by the ill-equipped vainglorious

young men sent out by these armchair dilettantes.

BIOGRAPHY OF THE AUTHOR, Richard N. Moersch M.D.

It may seem strange that so little was known about the great westward bulge of Africa,

relatively close to Europe, at a time when the Western Hemisphere was mapped and colonized

- and the United States had just realized its independence . English soldiers and traders

were active in India and the Far East, and yet the source and even the direction of flow

of the Niger, one of the great rivers of the world was unknown. No European of recent

memory had stepped foot in fabled and wealthy Timbuktu. There was no sense of West Africa

as a historical entity, although it was one of two major centers of population on the

continent. The two paramount reasons for this were its geographic isolation and the

penetration of Islam into Africa. The enormity of the Saharan Desert to the north and east

and the pestilent and deadly jungle to the south and east effectively barred penetration

from the outside. The Niger basin was basically a Moslem world with pockets of Animism,

and the rulers were determined to keep outsiders away.

There had been great kingdoms in the area, the three most important being that of Ghana

in the eighth through the tenth centuries, the Mali Empire in the twelfth and thirteenth

and that of the Songhai for the next two hundred years. All three were wealthy, powerful

and sophisticated. An Arab merchant, visiting Ghana described its sovereign as the richest

ruler in the world, while another, two hundred years later was astounded by the prevalent

peace, order and racial tolerance. Learning also accompanied the Islamic penetration and

important universities existed in Timbuktu and Gao well before the founding of Oxford and

Cambridge. A combination of circumstances led to the deterioration of these stable

empires: southward expansion of the Sahara, military encroachment from Morocco and the

Portuguese coastal explorations, giving them access to the gold fields south of the Niger.

By the time of the founding of the Africa Association little was known of this large blank

area on European maps. Two incredible Arab scholar-travelers of the fourteenth and

sixteenth centuries, Ibn Batuta and Leo Africanus provided most of what was known and even

they could not agree on whether the Niger flowed toward the east or westward. If more was

to be learned, to satisfy the curiosity of that inquisitive age, someone was going to have

to overcome considerable obstacles to reach these regions.

As for the Niger itself, it was a most unusual river, a joining of two distinct rivers

which had originally flowed in opposite directions. The western or upper Niger, called the

Joliba, arose near the Atlantic and went northeasterly 500 miles beyond Timbuktu, draining

into the salt lake of Juf. The Quorra originated in the mid Sahara and ran south to empty

into the Gulf of Guinea. The gradual drying of the Sahara over centuries produced a

shifting of the rivers and the capture of the Joliba by the Quorra. The great bend of the

Niger marks the site of the capture. As can be imagined, this served to contribute to the

confusion regarding the river and its lands..

The renamed Saturday Club did not dawdle; within a month the first young explorer was

on his way. The early explorers were sent out unprepared and ill-equipped, with vague

instructions regarding their goal. The principal end was to establish the course and lands

of the Niger, with attainment to Timbuktu in the background. The initial volunteer was

John Ledyard, a 37 year old American adventurer. Born in Connecticut, he attended

Dartmouth College to be groomed as a missionary to the Indians, by Eleazor Wheelock,

founder of the college. He grew restless however, and after a few months chopped down one

of the local pines , carved it into a rude dugout and paddled away to live with other

Indian tribes in the Northwest, adopting their customs. The boathouse for the Dartmouth

rowing crew bears his name. Four years later he showed up in England and talked himself

into joining the last expedition of Captain Cook. On this voyage he saw Africa, India, the

Antarctic and sailed through the Bering Strait; he was with Cook when the great navigator

was killed on the island of Hawaii. Five years later he appeared in Paris where he was

befriended by Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson and with their support headed across Russia

and Siberia by horse-drawn sledge, investigating similarities between tribes there and the

Indians of North America. A victim of changing political winds, he was arrested as a

French spy, 100 miles from the Pacific coast, dragged back to the Polish border and

banished from the country. He made his way back to London, visited Sir Joseph Banks and

became the first volunteer. Six weeks after returning from Siberia he was on his way to

Egypt, from where he proposed to strike thousands of miles west across the Sahara,

searching for the Niger and its origins.The tragic anticlimax to this heroic beginning is

that he contracted intestinal disease while on the Nile, and after taking a purgative

died, vomiting blood.

While Ledyard was Alexandria-bound, a second recruit was found. Simon Lucas was the son

of a wine merchant and an acquaintance of Beaufoy. As a youth, while traveling to Cadiz to

learn the wine trade, he had been captured by Barbary pirates and sold as a slave in

Morocco. While a royal slave he had learned much of the court and the language, and

sixteen years later returned to London as "Oriental Interpreter" to the Court of

St. James. As an alternative to the east-west approach of Ledyard, a north-south

investigation was proposed and he sailed for Tripoli., arriving in mid-October, 1788.He

met the Bashaw of Tripoli to seek his help and was told that the time was impropitious

because of tribal warfare in the Fezzan. Turning elsewhere, he enlisted the aid of two

sheriffs of Fezzan, who offered to guide him there. He set out in Arabic disguise, but

when the first governor he met again warned him of danger ahead he stopped. His two guides

finally became impatient and left without him. While Ledyard was precipitous, Lucas was

overly cautious; he left Africa and next was heard from in Marseilles in June 1789,

penniless and apologetic. He did tell the Association that he was bringing back much

information and packets of seeds, but did not feel himself cut out for exploration. Civil

service was more to his liking and two years later he was named to the post of consul in

Tripoli.

The failure of the attempts to reach the Niger from the east and from the north did not

deter the Association, and in July 1790 a third candidate was interviewed. Daniel Houghton

was a sturdy and cheerful Irishman, a retired army major. During his career he had been

posted on Goree Island, just off the coast of Senegal, where he had learned the native

Mandingo language and had become friends with native princes. Bankrupt and desperate for

employment, he asked only for 800 pounds for expenses. When he sailed he left behind his

wife and three children; the Association sent her the sum of 10 pounds. Banks explained

that "As an Association, they were not justified in appropriating money subscribed

for the purposes of discovery to the maintenance of individuals, who happened to be

connected to those whom they employ".

Houghton was to move up the Gambia River, approaching the Nile from the west. Almost

immediately he ran into trouble, having to swim across the river to escape traders who

were trying to kill him. Many of his supplies were burned in a mysterious fire and much of

what was left was stolen as he moved inland. His only communication - a letter to Beaufoy

that slowly made its way back to London - suggested that he remained in good spirits and

added that he had met a merchant who would guide him to Timbuktu. Beaufoy thought that he

had good chances of success, adding that "such is the darkness of his complexion that

he scarcely differs in appearance from the Moors, whose dress in traveling he intended to

assume". A scribbled note to a local trader some months later was the last word from

him, but it did say he had reached the village of Simbing, halfway to his goal. Nothing

further was known until five years later when another British explorer was shown the site

of his robbery and murder at that village. Houghton did report that the flow of the Niger

was to the east, his principal achievement. His wife wound up in debtor's prison.

The next candidate - and the one who would

achieve the most renown - was again a protégé of Sir Joseph Banks. A nurseryman of

London, James Dickson, had written several botanical monographs and was a friend of Banks.

Dickson's Scottish wife had a younger brother who had just graduated from medical school

in Edinburgh and was casting about for a position. Dickson introduced him to Banks, who

arranged a position for him as ship's surgeon on an East India Company ship bound for

Sumatra. The young Munro Park would return a year later with information

on eight new species of fish and a great thirst for travel. In addition, young Munro was

consumed with ambition. While on the way to Sumatra he wrote to Dr. Thomas Anderson, the

Selkirk surgeon who had helped him get into medical school: "I have now got upon the

first step of the stair of ambition....Macbeth's start when he beheld the dagger was a

mere jest compared to mine".

The next candidate - and the one who would

achieve the most renown - was again a protégé of Sir Joseph Banks. A nurseryman of

London, James Dickson, had written several botanical monographs and was a friend of Banks.

Dickson's Scottish wife had a younger brother who had just graduated from medical school

in Edinburgh and was casting about for a position. Dickson introduced him to Banks, who

arranged a position for him as ship's surgeon on an East India Company ship bound for

Sumatra. The young Munro Park would return a year later with information

on eight new species of fish and a great thirst for travel. In addition, young Munro was

consumed with ambition. While on the way to Sumatra he wrote to Dr. Thomas Anderson, the

Selkirk surgeon who had helped him get into medical school: "I have now got upon the

first step of the stair of ambition....Macbeth's start when he beheld the dagger was a

mere jest compared to mine".

A year after his return from the East Indies, Park offered his services to the African

Association. The interviewing committee found him to be " a young man of no mean

talents who has been regularly educated in the medical line.... and sufficiently

instructed in the use of Hadley's quadrant to make the necessary observations; geographer

enough to trace his path through the wilderness, and not unacquainted with natural

history". His offer was accepted and it was decided to recruit 50 more men to act as

his escort.

Impatient to depart however, Park sailed alone, telling his brother that there was no

doubt that he would "acquire a greater name than any ever did". He bore a letter

of credit for two hundred pounds and an introduction to a fellow Scot, Dr. John Laidley,

who ran a slave trading post on the Gambia River and had seen Houghton off on his fatal

journey. As did most Europeans arriving in West Africa , he contracted a febrile illness -

grudgingly called "the seasoning" and remained four months at Dr. Laidley's

entrepot recovering from this. He then set out with an English-speaking Mandingo guide, a

slave called Demba, a horse and two asses, food, an umbrella, a sextant, a compass, a

thermometer, two fowling pieces and two pistols.

Within a short time he was accosted by a native who told him that he was now in the

Kingdom of Walli and would have to pay duty. This scenario was replayed many times as he

moved inland, every petty monarch demanding some sort of bribe. One was pleased with the

gift of the umbrella, repeatedly furling and unfurling it before his court, while another

demanded his prized blue coat, dazzled by its silver buttons. That might call into

question not only the tyrant's greed but also Park's judgment in choosing apparel for

rainforest exploration. In the Kingdom of Bondou he was seized by horsemen and threatened

with death or dismemberment. The king's concubines were fascinated by the color of his

skin and the sharpness of his nose. When he responded in kind by praising the glossiness

of their skin, the ladies replied that "honey-mouth" was not highly regarded. He

was released however, thanks to their entreaties and trekked onward, but was seized once

more at Ludamar, a squalid little village near the desert. Here he was held for two months

and suffered the desertion of his interpreter. He was made to repeatedly dress and

undress, as the villagers had never seen buttons in use. The ladies came to his rescue

again, and after escaping involvement in a tribal war, he pushed on alone - only to be

robbed again within a few days and left to die of thirst. A freak rainstorm saved him and

on July 26, 1796 finally reached the banks if the Niger, in the company of some wandering

nomads who had taken him in. . He described his feelings on reaching "the

long-sought-for majestic Niger, glittering in the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at

Westminster, and flowing slowly to the eastward. I hastened to the brink, and having drunk

of the water, I lifted up my fervent thanks in prayer to the Great Ruler of all things,

for having thus far crowned my endeavours with success".

The King of Segou, however was anxious to get rid of him and gave him 5000 cowrie

shells and a guide as an inducement. The latter, hearing of his struggles to reach the

river, asked him "are there no rivers in your own country, and is not one river much

like another?". They left Segou, heading north toward Timbuktu. He had no money to

hire a canoe and struggled by foot into the marshy and trackless area of the internal

delta of the Niger. On August 25 he was robbed again, stripped of everything but a shirt

and some ragged trousers. He straggled on another three weeks, depending upon the kindness

of strangers for sustenance. At this point he surrendered and joined a passing slave train

heading west for the coast, promising the trader a reward if he arrived. Eighteen months

after leaving he returned to Dr. Laidley's post, having been long given up for dead. Here

he signed on as ship's surgeon on an American slave ship; the ship was bound for Carolina

with 130 slaves, but was diverted to Antigua by bad weather - eleven slaves died on the

crossing. From there he caught a Chesterfield packet and arrived in Falmouth on December

22, 1797. Lionized by the English, he wrote his account of his travels - an instant

best-seller. He was not well however, and returned to Scotland where he married the

daughter of his original sponsor and settled down to the life of a country doctor

While Park was still missing and unheard of, the Africa Association had been busy,

recruiting yet another young explorer. Frederick Hornemann was a German and the son of a

Lutheran pastor. He was a student at the University of Gottingen, where one of his

professors was J.F. Blumenbach, an ethnologist who was working on a classification of

races based upon the shape of the human skull. Blumenbach was a friend of Banks (a large

and eclectic group it seems) and referred his student to London, citing his good mind and

robust constitution. Hornemann was offered 200 pounds a year and, in addition, his mother

was promised an annuity in the event of the young man's death - a first for the armchair

explorers.

Hornemann's route was to be the previously unsuccessful one from Cairo across the

Sahara, and he left London for the Mediterranean and Alexandria just as Napoleon was

moving the Grand Armée on Egypt, in the Summer of 1797. Arriving ahead of the French, he

met a fellow German, Joseph Frendenburgh, who was living life as a converted Moslem.

Hornemann hired him as an assistant and began learning Arabic in preparation for his trip.

Delayed by an outbreak of the plague, his source of funds was cut off when the French

defeated the Mamelukes at the Battle of the Pyramids. Determined and resourceful however,

he made friends with some of the many scientists Napoleon had brought to Egypt with his

army, and , through them, made the acquaintance of Bonaparte himself. The little general

was taken with the young man and provided him with visa and moneys to start his trek; he

even offered to forward any communications to the Africa Association in London, despite

the state of war existing.

In September, 1798, Hornemann and Frendenburgh headed west in a caravan heading for the

Fezzan. For all his preparation the young explorer was a poor mock-Moslem and was soon

discovered when he was seen making sketches of some ancient ruins they passed. When

finally confronted they pled on the basis of Moslem laws of hospitality and read from the

Koran so convincingly that they were accepted as infidels striving to learn. The caravan

reached Murzuk - in the Fezzan - and Hornemann remained there seven months. Frendenburgh

died there and with no caravans heading south, Hornemann turned north to Tripoli, where he

was taken in by Simon Lucas, who we met earlier in our story. From there he wrote to

Banks, telling him " pray sir, do not look upon me as a European but as a real

African and a Moslem."

He was back in Murzuk in the spring of 1800 and from there joined a caravan heading

south, hopefully to the Niger and Timbuktu. He was never heard from again. The African

Association published his journals, as relayed from Tripoli, and presented a copy to

Napoleon - while still at war. Almost twenty years later, other explorers tracking the

area spoke with people who had accompanied him. He did reach the Niger and died there of

dysentery. He had fully transformed himself into a Moslem and shown such compassion and

caring for others that he was regarded as a Marabout - a holy man. There is a real

nobility to this young man's life, cut off before the age of thirty. a beloved stranger.

About the time that Hornemann was dying, Munro Park was suffering from severe

restlessness and wanderlust in Peebles. He wrote to Banks of his lack of satisfaction in

the life of a country doctor and a wish for a more adventurous career. Banks replied that

he would certainly recommend him, but that the British government was now taking an

interest in such explorations, slowing down the process. Quite typically for governmental

initiative, administrative wranglings led to a four year delay as parties rose and fell

and the war with France proceeded apace. In the autumn of 1802, Park was summoned to

London and offered command of a military party, to explore that part of the Niger beyond

where he had gone before and determine where it finally emptied - whether into Saharan

sand or the ocean. Ambition was a stronger pull than a growing practice, a wife and three

children. He told his friend , Sir Walter Scott, that "he would rather brave Africa

and all its horrors than wear out his life in long and toilsome rides over the hills of

Scotland".

More delays ensued and he finally left England in January 1803, sailing from Portsmouth

to Goree, the slave-trading island just off-shore from present-day Dakar. The small

British post there was staffed in large part with condemned criminals living under

appalling conditions: of a garrison of 332 men, 78 had died in the year preceding Park's

arrival. It is no small wonder then that Park had little difficulty recruiting the

authorized 33 men to accompany him inland from the coast. Ragtag they were as they headed

into the rainforest just as the rainy season was about to start. Struggling through the

endless swamps, the woebegone little party did not reach the Niger until late August, two

months behind schedule, by which time three-quarters of the party were dead and all the

pack animals either dead or stolen.

He purchased canoes for the ten remaining men and headed downriver, heroic and

foolishly optimistic. A month later he was in Segue with King Mansong, who had bribed him

with cowrie shells to turn back to the west nine years before. He announced that he was

now going down the river till it met salt water, so that the English traders might, in

time to come, trade directly with the people of the Niger, cutting out the Moorish

middlemen and their caravans across the Sahara through Timbuktu. The chief effect of this

was to alert the Moors, who would understandably do all they could to block him. The king,

anxious as ever to be rid of him, let him pass and even traded him two half-rotten canoes

for some English muskets. Further trading down-river , infuriated the Arabs, and Park, now

aware of the danger, consolidated his shrinking force into one boat, lining its sides with

bullock hides for protection. His pathetic force was now down to four soldiers and three

natives to paddle the boat., itself a makeshift craft assembled from parts of the two

leaky canoes.A local guide, Ahmadi Fatouma, claimed to know the river and was hired to

lead the way. On November 20, 1805 the remnant party took off down the river; like

Hornemann from Murzuk, they were never heard from again.

A year later, reports reached the British consul in Morocco that Park had been seen in

Timbuktu, and four years after that a Bombay newspaper stated that he had perished, this

based upon gossip heard by a pilgrim to Mecca. The outcry at home lead to the hiring of

the Mandingo guide Isaaco, who had been with the party between Goree and the Niger, and

who had forwarded all of Park's journals back to London . Isaaco headed out in 1810 and on

arriving at the Niger two months later found the one man who could answer the questions;

Ahmadi Fatouma. The latter said that Park had realized that he was in unfriendly and

potentially hostile territory and had elected to make a run for it, staying in the middle

of the river on the armed boat for however long it might take them. This, of course,

flaunted the custom of the river calling for repeated stops asking permission to go on and

paying tolls at every juncture. By ignoring tradition and by firing at anyone trying to

stop him he ensured the enmity of all who lived by the river. Despite the tenuous

situation they found themselves in, Park remained confident and in his last letter to his

wife, carried out by the Mandingo guide Isaaco, he wrote: "You may be led to consider

my situation as a great deal worse than it really is ..... the healthy season has

commenced, so there is no danger of sickness .... I think it is not unlikely but I shall

be in England before you receive this .... the sails are now hoisting for our departure to

the coast".

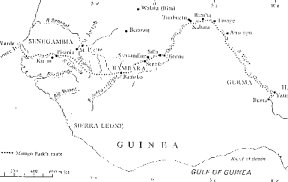

Muno Park's route

Muno Park's route

The pathetic little boat, dubbed the "Schooner Joliba" came under almost

constant attack. Park and his party responded in kind and gained a reputation as

"Tanakast" or wild beasts, a tale retold for decades by the natives of the area.

They did break free of the Moorish-controlled region - the great bend of the Niger as it

reverses its direction - and headed south into what is present-day northern Nigeria.

Successfully negotiating the high rapids and avoiding the aggressive massed hippos, they

reached the Kingdom of the Yauris, just six hundred miles from the sea. Here he believed

himself to be in friendly country and went ashore, presenting gifts to the king. This

worthy was displeased with the quality of the presents as well as the word that Park and

the English would be returning, placed Fatouma in irons and ordered his troops to attack

the little boat at Bussa Rapids, where the river narrowed markedly. The following day the

Yauri struck at the Joliba as she attempted the rapids, hurling spears, pikes, arrows and

stones. The paddlers were soon killed, while Park and the soldiers attempted to escape by

jumping into the roiling water, where they soon drowned.

In death, Park was celebrated as one of England's great heroes and compared to such

luminaries as Captain Cook and Sir Walter Raleigh. Tennyson's words about Ulysses could

apply to him:

Yet all experience is an arch where thro'

Gleams that untravel'd world, whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

For all that, however, Park added very little to the knowledge of the geography of West

Africa, nor did he discover any new trade routes, so desired by the British. All of his

journals and belongings disappeared and were never recovered.

The still energetic African Association took a deep breath, sending out yet another

explorer, Henry Nicholls. Having failed in attempts from the north (Libya), the east

(Cairo) and the west (Gambia), it was proposed that a try should be made from the south.

The site chosen from which to strike inland was from British trading posts on the Gulf of

Guinea. It was not known at this time that the Niger River actually emptied into the Gulf

of Guinea, and as a consequence the starting point was in truth the destination. In the

event, Nicholls sailed from Liverpool on November 1, 1804, bound for Calabar - Park was

still alive and planning his final, fatal descent of the Niger. By February he had sent a

message to the Africa Association describing his health and spirits as both good and no

obstacles apparent. Two months later he was dead of "the African Fever".

By this time, there was a gradual transition in the direction provided to West African

exploration. The driving force of the Africa Association, Sir Joseph Banks was seriously

ill and confined to a wheelchair, although still involved with many governmental and

private committees. At the same time the British Foreign Office and Admiralty chose to

take an increasingly active role. The torch was being passed although the Africa

Association continued to play a role until it was absorbed into the Royal Geographic

Society in 1831. The planning, direction and results of the ongoing exploration remained

largely unchanged.

In 1815, the Colonial Office sent off Major John Peddie of the 12th Foot to further map

the course of the Niger, recruiting volunteers from the Royal Africa Corps. He arrived in

Senegal in November and promptly died of "fever". He was replaced by Captain

Thomas Campbell but the attempt to move inland was hampered by bee attacks and they made

little progress before turning back. Then Campbell died and in turn was replaced by

William Gray and John Dochard, the military surgeon with the group. With a hundred men and

two hundred pack animals they headed inland again. The journey was the usual awful

experience, most of the men dying, Gray captured (and later released) and Dochard and

seven men barely reaching the Niger before being turned back.

The following year Captain James Kingston Tuckey was sent up the Congo to learn whether

the Congo and the Niger entered the ocean together - the later-discovered truth was that

their mouths were nearly nine hundred miles apart. His selection was rather interesting in

that his prior experience consisted of having written four books on Maritime geography and

having surveyed Sidney harbor. His team of fifty-four included a Norwegian botanist and a

gardener from Kew. Their two boats could not enter the mouth of the Congo because of the

currents; changing to small boats, they made it to Yallala Falls and then overland for two

hundred miles until the weakened carriers refused to go further, at which point they

turned back. When they reached the coast and their boats, thirty-five of the men,

including Tuckey, were dead. Little of significance was learned.

The year after that a letter from a young naval officer, W.H. Smyth, to Admiral Penrose

was passed on to John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty. Barrow, who served in

that post for forty years is best remembered as the man responsible for sending many naval

ships to the high Arctic in search of the Northwest Passage. The letter suggested that the

northern route across the Sahara was still a better approach to the heart of West Africa

than the recent fetid and pestilent ones of recent years. Barrow agreed and was seconded

in this by Hanmer Warrington, a Falstaffian character who was British consul in Tripoli

for thirty-two years. Once again, an unusual team was chosen for the endeavour; The leader

was an introverted and careless young surgeon by the name of Joseph Ritchie. He was

accompanied by a twenty-three year old naval officer, George Lyon and John Belford, a

shipwright who was to build a boat if they ever reached the Niger. The Colonial Office

gave them two thousand pounds for supplies and most of this went for such articles as a

load of corks to preserve insects on, two chests of arsenic and six hundred pounds of

lead.

On March 18, 1818, they were received by the Bashaw of Tripoli and told they could head

south with the Bey of Fezzan as part of a slave-raiding caravan. Ritchie's instructions

from Lord Bathhurst were to "proceed under proper protection to Timbuktoo .... and

collect all possible information as to the further course of the Niger ....". Already

there was a subtle shift from the river itself to the important trading post at its

northern bend. Increasingly, the raison d'etre for sending young men to an inhospitable

and dangerous locale was the possibility of commercial exploitation rather than the

accumulation of knowledge, as originally proposed by the prototype "Fortnightly

Club". Interestingly, Ritchie, who was a good friend of John Keats, did take a copy

of the poet's Endymion with him to cast into the middle of the Sahara as a romantic

gesture.

Their first destination was the Fezzan capital of Murzuk, which Hornemann had visited

twenty years before. It was reputed for its unhealthy climate and soon after arriving

there Lyon had dysentery, Bedford was stone-deaf and Ritchie had a biliary fever with

delirium. Without funds, they were reduced to beggary and discovered that the local

inhabitants were forbidden to trade with them. Within six months Ritchie was dead, Bedford

was able to utilize his carpentry skills in making a coffin for his leader, and the two

survivors beat a retreat back to Tripoli. The only information brought back by Lyons in

return for their suffering was wrong; he reported that the Niger flowed into Lake Chad and

from there on to the Nile.

Acting on this misinformation, Barrow recruited an even more dysfunctional team in 1820

and sent them southward with the government's blessing. Walter Oudney was yet another

Scottish surgeon, small, self-effacing and already tubercular. He, in turn, recruited his

neighbor, Lieutenant Hugh Clapperton, a naval hero and a fine figure of a man. The third

member of the team was Lieutenant Dixon Denham, an army hero and instructor at Sandhurst.

He was also priggish and small-minded while Clapperton was over-proud and stubborn and

Oudney overmatched by both. Ill will was apparent before they were well into the desert,

with the English Denham in constant conflict with the two Scots. Soon Denham and

Clapperton were not speaking and both were sending long and scurrilous messages back to

London regarding the other. These reports were carried slowly back across the Sahara by

messengers always sent in pairs as it was assumed one would perish on the way. The most

damaging of these was the report by Denham that he suspected Clapperton of homosexuality,

a career-ending innuendo in those days.

Despite this virulent enmity, they remained in the interior for nearly four years

during which time they did reach Lake Chad - the first Europeans to do so. For over two

years they ranged widely around the great inland lake and to the south and west of there

in an attempt to define the course of the Niger and where it emptied, an ultimately futile

quest. During the course of these peregrinations Oudney died, Clapperton was rebuffed by

the Sultan of Sokoto and Denham captured by Hausa warriors, escaping only after being

stripped naked and losing all his equipment and notes. The two antagonistic, surviving

explorers continued to live apart, communicating only by letter. They did agree, however,

that it was time to return across the Sahara to Tripoli, and in September, 1824 they

headed north. After an agonizing five month trek they reached Tripoli, where both

presented their version of the facts of the expedition. Denham was a public idol for a

short time after which he was honored with the post of governor of Sierra Leone, where he

died of "fever" at the age of forty-three. Clapperton recovered from his malaria

and was anxious to resume the search for the course of the Niger, but in the meantime

another rival for African glory appeared on the scene.

Yet another Scotsman, Major Alexander Gordon Laing, presented himself as a candidate

for Nigerian heroism. Precocious and clever, he was aide-de-camp to General Charles

Macarthy in West Africa. Consumed with ambition, he pulled strings and was given

permission to attempt to reach the Niger from Sierra Leone. In 1822, while Denham and

Clapperton were fulminating against each other by the shores of Lake Chad, he made his

attempt. This try was unsuccessful, but he was so caught up in the excitement of the chase

that he overleaped his senior commander to seek permission for another exploration. The

bypassed General Turner fired off a spiteful letter to Lord Bathhurst in response: "I

would not fulfill my duty either to your Lordship or to the Service, were I not to

characterize as unwise, unofficerlike and unmanly, the conduct of Captain Gordon Laing in

this country ...... I humbly beg yor Lordship, in the name of the Regiment, that he may be

removed from it - and that we may not be subject to the mortification of his calling us

Brother Officers."

Despite this, Laing's persistence was rewarded, he was given leave-of-absence and

directed to head for Tripoli with the goal of reaching Timbuktu and discovering the

drainage of the Niger. When he arrived, the comic-opera consul Warrington was engaged in a

diplomatic war with the newly appointed French consul Joseph-Louis Rousseau, made worse by

the fact that Rousseau's son was courting Warrington's daughter, a Libyan Romeo and

Juliet. Laing's appearance was a godsend, Warrington pushed his compliant daughter in the

Scot's direction and two months later they were married. The day after the unconsummated

marriage, Laing left for his trans-Saharan trip to immortality.

Rather than the route used by Clapperton and Denham, his, in the company of Sheikh

Babani, headed more westerly, two thousand miles across the heart of the great desert

occupied chiefly by lawless Tuaregs living off plundered caravans. It took Laing more than

a year to reach Timbuktu and a more difficult land voyage would be hard to imagine. His

spirits were high though and he hoped to reach the fabled city before Clapperton could

"snatch the cup from my lips".He later said that " if the termination of

the Niger is Clapperton's object, "he might as well have stayed home, for it is

destined for me". Six months after leaving his virgin bride, he reached In Salah, in

present-day Algeria, and there found merchants who had been waiting as long as ten months

to go south, for fear of the marauding Tuaregs. For Laing, racing against Clapperton in

his mind, this delay was intolerable, and he announced that he would proceed across the

rocky Tanezrouft alone. The merchants were shamed by the driven young man, agreed to go

and on January 9, 1826 the caravan left, with three hundred camels and one hundred fifty

armed men. In addition to the fame he so desperately coveted, a 10,000 franc prize was

announced , earlier in the year, by the Geographical Society of Paris for the first person

to reach Timbuktu and return to Europe alive. Laing knew of this and was also aware that

Clapperton was on the march again, attempting to reach Timbuktu from the south. The race

was on!

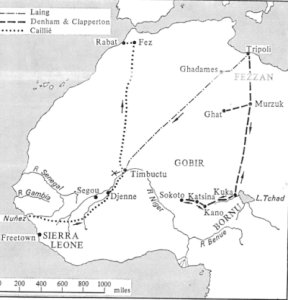

The Tripoli Route

On January 26 Laing sent an optimistic letter to London, saying that the caravan had

met with friendly Tuaregs and that "... my prospects are bright and expectations

sanguine." Unfortunately, at just this time they were joined by twenty heavily-armed

Ahaggar Tuaregs, who were accepted into the caravan. Three days later, at Wadi Ahnet where

they had stopped overnight, the new arrivals attacked Laing and his party in their tents

at night. Two were killed and Laing was dragged from his tent and hacked at with swords,

being left for dead. Amazingly, he survived and joined by three companions who had escaped

into the desert in the confusion, continued on another four hundred miles across the

desert till reaching the camp of a friendly Arab chieftain. He remained here for three

months, while recuperating. During this time he sent a report to Warrington which did not

reach Tripoli for two years; in it he detailed his wounds. There were twenty-four in all

including a musket ball wound that had fractured his hip and grazed his spine, a broken

jaw and partial amputation of his left ear, five cuts on his right hand to the level of

the bone, broken forearm bones, long lacerations of both legs and his left arm and a

broken wrist. In addition, he began to act in a somewhat irrational manner, adding in a

note that " I shall do more than has ever been done before and shall show myself to

be what I have ever considered myself, a man of enterprise and genius ".

While recovering a mysterious epidemic swept through the camp, killing all his

remaining companions and the friendly chief with half of his village. Despite this, Laing

was more determined than ever to push on and with a party of the disease survivors headed

south in July and finally reached Timbuktu on August thirteenth, a little over a year

after leaving his virgin bride. The timing was poor, as a Fulani zealot Seku Hamadu was in

the process of wresting control of the city from the Tuaregs in a holy war. The remaining

merchants however greeted him warmly and he remained for five weeks, talking with scholars

and examining records. The two story mud house where he lived is still standing to this

day. More bad news arose however, as Hamadu's overlord, Sultan Bello of Sokoto sent word

that Europeans were not to be allowed in the Sudan.

Laing was told that he must leave at once and he sent one final message to Warrington

on September 26, stating that he was heading southwest toward Segou but saying almost

nothing about Timbuktu, preferring to bring his observations with him in his journal. No

word was heard from him again. His small party made it no further than Sahab, thirty miles

to the north where Sheikh Labeida, his guide, turned on him and killed him. Nothing was

known of his death or the manner of it, beyond rumor, for eighty-five years. In 1910 a

French team headed by Bonnel de Meziere was sent to the area acting on information

provided by an elderly nephew of the Sheikh; skeletal remains were dug up and reported by

examining doctors as consistent with those of a European adult.

There was one final surpassing consequence of Laing's epic trip. His journal was never

recovered but in 1828 the Paris newspaper l'Etoile reported that Laing was dead, based

upon a letter unsigned but sent from Sukhara, Tripoli, the name of the country home of

Consul Rousseau, Warrington's foe and the father of the young man who had courted Emma

before Laing's arrival. The source of his information was never disclosed but Warrington

was convinced that Rousseau had obtained the journal and that furthermore the French had

connived in the assassination. Warrington blamed the Bashaw as well, along with his

French-educated minister, Hassan D'Ghies, and lowered the British flag and boycotted the

Bashaw. The Royal Navy's Major James Frazer was sent to investigate and was confronted by

the news that D'Ghies had confessed and then fled Tripoli with the help of the American

consulate. The Bashaw read the so-called confession to the assembled diplomatic corps,

Warrington re-hoisted the flag and Rousseau escaped to France. In Paris it became a matter

of national honor and a French naval squadron was dispatched in 1830, under the command of

Admiral Rosamel, to force a retraction of the charges. This he accomplished , following

which the English formally withdrew their support of the Bashaw. Without the support of

the competing powers and their navies, the Bashaw was fatally weakened and overthrown in

1835, Tripoli returning to Turkish rule. One final consequence was that the suspicious

Turks would permit no further exploration of Africa from this area.

As Laing was struggling south across the Sahara to Timbuktu and his death, Clapperton

and his assistant and manservant John Lander were ascending the Niger north from the Gulf

of Guinea. Many of the party were already dying of malaria but like all the intrepid and

doomed explorers before him, Clapperton pushed on, finally reaching Bussa, where Park was

ambushed. Their course beyond was slowed by the constant demands of petty village

chieftains and occasional romantic dalliances. In Wawa Clapperton was pursued by a rich

widow who he described in his journal as a "walking water-butt". Lander was even

more explicit, calling her a "moving world of flesh, puffing and blowing like a

blacksmith's bellows".

By mid-August, as Laing was entering Timbuktu, Clapperton was in Kano but by now sick

again and unable to travel. After five weeks of recovery, it was decided that he would

push on alone, leaving Lander to guard their by-now meager possessions. The trek was the

usual nightmare of misdirection, fatigue and illness culminating in the hostile reception

he received from Sultan Bello, the same despot who had ordered Laing out of Timbuktu a

month earlier. He was not permitted to go further, although for a while the situation

seemed better: his health improved, the Sultan seemed friendlier and Lander rejoined him.

Warfare intervened however, and as the Sultan fled Kano he took the two Englishmen with

him. Clapperton once again sickened, deteriorated and weakened and finally died in

Lander's arms on April 13, 1827.

Lander, the erstwhile servant and now quite alone, managed to make his way back to

their starting point in six months of illness, delay and trickery, reaching the gulf in

November, 1827 and London three months later. A modest hero, he retired to Cornwall and

quiet, but as so many before him, was lured back to Africa three years later and with his

brother finally made the ascent of the Niger from its mouth, completing the mapping of its

course, started nearly forty years earlier.

Timbuktu remained a mystery to Europe however, but the man who would achieve success

was already preparing himself. Rene Caillie was the orphaned son of a baker apprenticed to

the local cobbler. At the age of sixteen however, impassioned by his reading of Robinson

Crusoe, he walked away with fifty francs in his pocket and a new pair of shoes. His

wanderings took him to West Africa and then the West Indies, where he read Mungo Park's

Travels and realized what he would do with his life. He returned to France, learned Arabic

and then pestered the directors of a French team that was sent in relief of a British

group missing east of Dakar. He was allowed to join them and returned two years later,

with malaria but alive and with renewed determination. He next spent a year living as a

Muslim ascetic in the Sahara, returning to France to earn a little more money and then

heading back to Africa. For another year he hardened himself, learned native languages,

accumulated a small nest-egg and then believed himself ready. He would travel alone and

inconspicuously, unknown to the world. He became Abd Allahi and joined a caravan heading

east from Sierra Leone. It was March, 1827; Laing had been beheaded six months before and

Clapperton would die in a month.

Three months later he had reached the Niger, by this time barefoot and devastated by

malaria and dysentery. Scurvy was to follow, but he was fortunately nursed back to health

by an old crone who befriended him. After six weeks of a red-wood extract he improved and

slowly made his way to Djenne, a picturesque trading city south of Timbuktu, where he

first heard rumors of Laing's death. At Djenne he sold what he had left and boarded a boat

heading five hundred miles down river to Timbuktu's port of Kabara. Twice stopped by river

pirates, the boatmen hid Caillie beneath mats, paid tribute and sailed on. On April 25,

1828, they reached Kabara and Caillee walked the few remaining miles to Timbuktu.; he had

been traveling, alone and light, for exactly one year.

What he found did not meet his expectations; he described it as a "mass of

ill-looking houses built of mud". Nonetheless, he did remain there ten days, taking

notes and being shown the site where Laing was executed. His dwelling place, like Laing's

is still present today, marked by a small plaque. He seized the first opportunity to leave

though and headed north with a slave and gold caravan into the Sahara. It was the hottest

time of the year and two thousand miles with little water and fewer friends, but three

months later arrived in Tangier where the French consul slipped him on a boat bound for

Toulon.

His return lead to little interest, and it was only when the British questioned the

truth of his reports that national pride led the French to award him a gold medal and a

pension of three thousand francs a year. This pension was discontinued in 1833, amid

continuing doubts and he died in 1838 at the age of thirty-nine, penniless and depressed.

Years later, other explorers were shown the house where he had lived in Timbuktu and the

unmourned hero was vindicated.

The succeeding years of the nineteenth century saw much warfare and jockeying by the

British and French for control of West Africa, the English because of its trade importance

and the French as a military exercise. The explorers lived on, if faintly, in the history

books. Yet the story is a fascinating mixture of incredible bravery, egocentric drive,

unbelievable foolhardiness and imperial folly. All initiated by an eighteenth century

Fortnightly Club.