|

MEETING # 1631

4:00 P.M.

March 2, 2000

An American Aristocracy

The Livingstons

by Robert Eaton Morse

Summary

The Indians called it "The River That Flows Two Ways", because it is tidal

for the first hundred and fifty miles – all the way from New York up to Albany. Henry

Hudson, who sailed it in 1609 looking for a northwest passage to the Orient, christened it

the Mauritius, after the Dutch under whom he served. Ruler and sailor were both

disappointed: there was no northwest passage. Even so, by the end of the seventeenth

century, the river that bore Hudson’s name had become America’s busiest

commercial and military thoroughfare – and Robert Livingston, the young Scotsman who

had managed to possess himself of much of it’s central valley, was well on his way to

establishing the second of the great colonial American aristocracies. Virginia’s

first families had landed first, by just a few years.

Biography of the

Author

The author, Robert Eaton

Morse was born in Franklin, New Jersey in 1920. He attended Williams College and graduated

from the University of Virginia. During World War ll he served in the Army Air Corps from

1942 – 1946. His Masters degree was earned at New York University with subsequent

Doctoral work at Ohio State, Wayne State, and the University of California. He was in

private industry in various financial management capacities, later rejoined the U.S. Air

Force and served in a civilian capacity at a number of locations throughout the United

States. He is retired and involved in a number of community activities. The author, Robert Eaton

Morse was born in Franklin, New Jersey in 1920. He attended Williams College and graduated

from the University of Virginia. During World War ll he served in the Army Air Corps from

1942 – 1946. His Masters degree was earned at New York University with subsequent

Doctoral work at Ohio State, Wayne State, and the University of California. He was in

private industry in various financial management capacities, later rejoined the U.S. Air

Force and served in a civilian capacity at a number of locations throughout the United

States. He is retired and involved in a number of community activities.

An American Aristocracy – The Livingstons

1674 – 1700 Robert

In April 1673, at the age of eighteen, Robert Livingston sailed from Scotland for the

New World. He landed first in Charles town, Massachusetts in December 1673 and presented

himself to the prominent Winthrop family, his father, a Scottish clergyman's, connection

in the Bay Colony. He became acquainted with John Hull, a respected silversmith and fur

trader who was seeking new sources of beaver pelts for export to Europe. Because of

Livingston’s fluency in the Dutch language, acquired in his early years of residence

in Rotterdam Holland, he was considered by Hull to be an excellent candidate to serve as

Albany’s agent.

The fur trade in Western New England had so depleted the supply of beaver that

expansion further to the West was critical. Even though the English had seized New York

from the Dutch in 1664, they were unable to govern without the cooperation of the

entrenched Dutch merchants of the town of Albany, a small trading post situated 150 miles

upriver from Manhattan on the edge of the western wilderness.

The forests on the western frontier, across the Hudson River in the province of New

York, were also rich in beaver; but the supply of pelts there was under the control of the

mighty Five Nations of the Iroquois, who traded exclusively with the Dutch Merchants. In

trade, society, and day to day governance, the life of Albany was dominated by a small,

closed, jealous Dutch establishment, whose suspicions of everything English extended to

the inhabitants of the New England colonies – all of which had so far discouraged

John Hull from attempting to infiltrate the ranks of Albany trade.

It was therefor most expedient to Hull and the other Boston traders to have in their

employ a person who could deal one on one with the Dutch. Livingston was their man. During

his first few months in Albany, Livingston had taken pains to ingratiate himself with the

town’s most prominent personage, Nicholas Van Rensselaer, director of Rensselaerwyck,

the greatest of the Dutch patroonships.

The patroonships (which were called manors after the English takeover in 1664) were

mammoth land grants given on very easy terms by both the Dutch and English provincial

governments in order to promote quick settlement of New York’s vast territory. The

patroon or lord received his enormous parcel of land in exchange for a pledge to import

and establish a certain number of settlers within a fixed period of time. He also paid an

annual quitrent to the Crown, and in turn collected rents from the settlers who cleared

the land and planted crops. Tenant farmers signed on for life, might pay a larger quitrent

than their lord’s annual fee for his entire fiefdom, yet no tenant was permitted to

buy his farm. Title remained perpetually with the lord.

Renselaerwyck, which had been granted to Nicholas’ father by the Dutch West India

Co. in the 1630s, comprised upward of 700,000 acres on both sides of the Hudson, with the

town of Albany at its center. Nicholas, shortly after arriving in Albany in October 1674,

had been appointed as the director and 3 months later married the reigning belle of Albany

society, 18 year old Alida Schuyler, in what was very likely an arranged marriage between

the two early arrival families of prominence, Schuylers and Van Rensselaers.

The newly married couple moved into the patroon's house and in the house next door

lived Robert Livingston, a lively, able young man, eager for employment, ingratiating and

experienced in business.

Nicholas having neither the patience nor the inclination to administer his huge

holdings set about looking for an able secretary. And so Livingston became secretary to

Rensselaerwyck. Shortly after becoming the secretary he was appointed secretary to the

town of Albany and a few months later, secretary to the newly formed, extremely sensitive

Board of Indian Commissioners. Robert now had fingers in all the choicest pies:

Rensselaerwyck, the town of Albany, the colonial government and the Iroquois Council.

Singly, any one of the offices was a source of influence and prestige, together they could

exert enormous political leverage; on paper at least, he was sitting pretty.

The trouble was that all three of his employers had a bad habit of not paying their

salaries on time, if at all. So despite his income from the fur trade he was soon in debt,

but kept all of his creditors at bay until an event that transformed Robert in

everyone’s eyes; he married the recently widowed Alida Schuyler Van Rensselaer.

Alida had shared a childless marriage with Nicholas, some 20 years her senior, for

almost four years. In November of 1678 her husband was suddenly taken gravely ill and

shortly thereafter expired. Robert carried Alida off to the altar within the following

eight months.

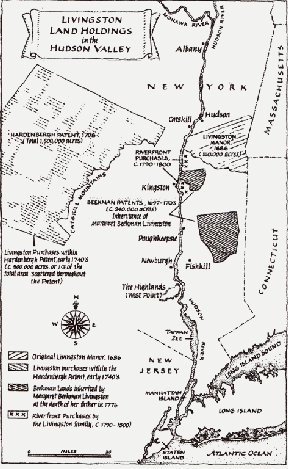

Soon thereafter Livingston embarked on a petition of acquisition of 2000 acres on the

East Side of the Hudson River south of Albany, directly across from the high peaks of the

Catskill Mountains. The final patent was issued four years later on November 4, 1684. One

year later, in 1685, he filed a petition to purchase an additional 300 acres to the east

of his riverfront property," in the territory called by the Indians Tachkanick"

– 300 acres that mysteriously doubled into " about 600" by the time the

patent was officially recorded a few months later. July 22, 1686 is the official date on

which Robert Livingston, a thirty–one year old immigrant merchant, son of a humble

Scottish clergyman, was by royal patent transmogrified into " Robert Livingston, Lord

of Livingston Manor". A patent which describes his two parcels of land as "

adjacent". The 2000 acres along the river and the 600 acres far inland had, as it

were, gobbled up the 157,000 acres in between making him owner of 160,000 acres of the

East bank of the Hudson River and master of a potential manorial manage straight out of

the Middle Ages. A dash of the gubernatorial pen added 250 square miles to Robert’s

possessions all in exchange for 28 shillings annual quitrent to the Crown of England.

The wording of Robert’s royal patent was identical to the standard, centuries old

English baronial grant, complete with vassals and quitrents, days riding, courts leet and

baron, and the right to appoint clergy. Had he arrived in New York a few years earlier,

when it was still New Netherlands and owned by the Dutch, his title would have been

Patroon instead of Manor Lord. Patroon or Lord, the title sounded much grander than it

was. Livingston Manor in 1686 was nothing more than a vast wilderness, untenanted,

unimproved and unprofitable. It took Robert some forty years to remedy that, and in the

meantime he matter-of-factly styled himself " Robert Livingston, Merchant".

Meanwhile the manor sat, waiting. The primary stumbling block was the tenant system

itself – a system whereby no tenant farmer, however industrious and ambitious,

however faithful in payment of rent, " fat hens" and days riding to his

landlord, could ever receive title to his farm. Naturally, the most enterprising and able

immigrant – men whose desire for independence and proprietorship ran just as deep as

Robert Livingston’s – chose instead to settle in the neighboring colonies of

Massachusetts and Connecticut, where sizable freeholds were plentiful.

New York manor lords had to settle for newcomers with no capital and no prospects.

Desperate to people their fiefdoms, the manor proprietors often ransomed whole families

out of indentured servitude and then offered them attractive lease terms: an initial

rent-free period of a year or more, free provisions for the first year, and seed gifts of

livestock and fruit trees. To the down and out, the tenant system offered a chance of

getting started, for which many were willing to sacrifice their independence.

From the proprietors’ point of view, settlement was agonizingly slow; during its

first three decades of existence Livingston Manor attracted only about thirty tenant

families. At that rate it takes a long time to turn 160,000 acres to profit, and meanwhile

the lord and lady of the manor lived in town and worked, just like everybody else. To a

large degree, Robert and Alida lived on credit and their wits, borrowing here, lending

there, and never letting their creditors compare notes.

Robert was extremely proficient at these elaborate financial balancing acts. He always

seemed to live well – and he was always short of cash. Like all provident parents,

they planned each son’s future with one eye toward his individual advancement and the

other on his usefulness to the family. The family’s role as an economic unit was

extremely important, every member was trained to make his contribution to the whole.

1700 – 49 First Generation: Philip and Robert

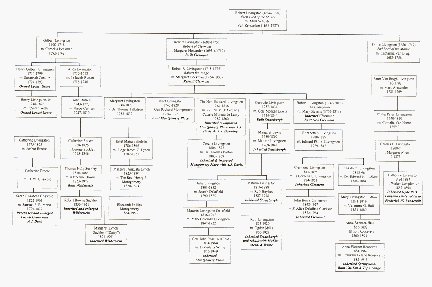

Robert and Alida had a total of ten children, six of whom survived to maturity, four

sons:

John, Philip, Robert, and Gilbert, and two daughters, Margaret and Joanna. John, the

oldest, was destined to become the second proprietor of Livingston Manor. However, since

the manor’s productive potential would be realized only in the distant future, John

was sent out in his teens to live with the Iroquois and learn the fur trade. Philip

embarked on a business apprenticeship with his Uncle Schuyler in Albany and Robert at age

12 had sailed for Edinburgh in 1698 to live with his Aunt Barbara and attend Latin School

in preparation for a career in law. As a younger son who would inherit neither the family

estates nor the family business, Robert required more elegant schooling then either of his

older brothers, John and Philip. Gilbert, at ten, was hardly old enough to bustle in the

world; still his character already seemed more to resemble that of his oldest brother,

John. Handsome and indolent, Gilbert had so far failed to distinguish himself at his

studies or to exhibit any enthusiasm for the profession his parents had chosen for him at

birth, the ministry.

In 1715, Robert (Lord of the Manor) was given the opportunity to obtain a royal

confirmatory patent from the British Crown for the Manor of Livingston. Believing that the

new patent would finally confirm his family’s title in perpetuity, free of any future

whims of royal governors and the London Board of Trade, he spared no effort on behalf of

it. The confirmatory patent was issued on October 1, 1715 and conferred on him the two

rewards for which he had come to America over forty years before, so hard even since:

property and security.

It also conferred a new priviledge: the manor’s right to send its own

representative to the Colonial Assembly. Robert had his own pocket borough and in 1716 he

took his place in the Assembly Chamber as representative from Livingston Manor.

To nobody’s great surprise, the Livingston tenantry continued through this

generation and the next – until the manor itself ceased to exist – to elect

their proprietor or one of his close relatives as assemblyman from the manor.

On May 27, 1718, Robert (Lord of the Manor) was elected Speaker of the provincial

Assembly. The position gave him greater political leverage than ever, which he used to

seize some succulent political plums for his offspring. Philip became his father’s

successor as Secretary for Indian Affairs, young Robert was appointed Clerk of the

Chancellery, Gilbert became escheator – general, and Robert’s nephew Robert was

named Mayor of Albany. When Peter Schuyler succeeded in maneuvering the latter out of

office in order to replace him with a Schuyler cousin, Robert Livingston demonstrated his

clout with London by getting the decision reversed.

In 1720 son John died, at age 40, causing a major dynastic reshuffling, the next

proprietor of Livingston Manor would now be Philip, the eldest, who at age thirty-eight

was a well established, highly respected, prosperous Albany Merchant and trader. He had

been married to Catrina Van Brugh, whose father was a former mayor of Albany, and they had

at that time five of an eventual nine children. The eldest named Robert (after his

grandfather). Philip and Catrina, firmly and comfortably entrenched in Albany’s upper

social stratum, privately found the prospect of life in an isolated manor

"homestead" far from appealing. But duty outweighed personal inclinations, and

Philip accepted his new responsibilities.

Robert’s new will left Gilbert some land near Saratoga and elsewhere in New York,

but a deep–seated fear of Gilbert’s improvidence led his father to cut him

completely out of the manor. Young Robert on the other hand was bequeathed a 13,000-acre

plot carved out of the manor’s southern end – a fact which cannot have failed to

gall both Gilbert and the dutiful Philip.

Upon Roberts’ (Lord of the Manor) death on October 1, 1728 his son Robert

succeeded him as the Livingston Manor representative at the autumn session of the Assembly

in New York City. It also ushered in an interlude of peace for the province of New York

and the family of Livingston. For the next fifteen years no French and Indian wars

threatened the town of Albany, and New York City’s streets were quiet.

Philip, Robert and Gilbert Livingston were not only utterly lacking in mutual

congeniality, they had also been raised – as most children were, at the time –

without regard for what we would call natural family affection. The emotional ties that

bind were far less important to parents in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries

than the economic and dynastic bonds that held a family together. Group values transcended

the individual value of any family member, and personal feelings were quite irrelevant.

The Livingston children, therefore, grew up utterly devoted to the Livingston Family

– its position, its economic health, and its prerogatives – but not necessarily

to one another personally. The three brothers, incompatible, uncongenial, and disputatious

as they were, invariably presented a solid front to the outside world.

It was therefore, perfectly natural that young Robert, on giving up the manor seat in

the colonial Assembly in 1729, the year after their father’s death, turned it over to

Gilbert (elections for manor representatives tended to be a mere formality, since all of

the voters were Livingston dependents.) Philip, already a member of the Governor’s

Council, was not available, so Gilbert it had to be. He kept the seat warm for nine years

until Philip’s oldest son, crown prince Robert, was ready to assume it.

Despite marriage and paternity, forty – year old Robert was, at the time of his

father’s death, still floundering. He had a few legal clients and a minor role in the

family trade, but there was no center, financial or otherwise in his life. His older

brother looked with scorn on Robert’s indetermination: Robert in turn continued to

despise Philip’s marketplace mentality, and the two remained on very cool terms.

What galvanized Robert was the assumption of his Hudson River

estate. Suddenly the future leapt into focus, and he knew that he wanted to become, as

quickly and painlessly as possible, a country gentleman. The vision transformed this

lackadaisical and indolent creature into a man of vitality and purpose. Ascertaining that

his law practice was paying out too slowly, he abandoned it to become a full – time

merchant. It soon became apparent that he had inherited his father’s eye for a shrewd

investment and his acute sense of timing: a new round of French wars broke out, Robert

launched himself into privateering and within a few short years had become positively

prosperous. What galvanized Robert was the assumption of his Hudson River

estate. Suddenly the future leapt into focus, and he knew that he wanted to become, as

quickly and painlessly as possible, a country gentleman. The vision transformed this

lackadaisical and indolent creature into a man of vitality and purpose. Ascertaining that

his law practice was paying out too slowly, he abandoned it to become a full – time

merchant. It soon became apparent that he had inherited his father’s eye for a shrewd

investment and his acute sense of timing: a new round of French wars broke out, Robert

launched himself into privateering and within a few short years had become positively

prosperous.

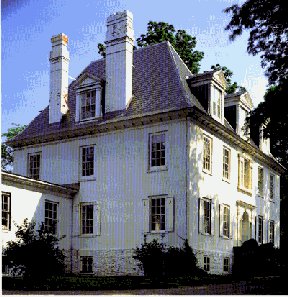

Meanwhile, long before he could afford it, he began constructing a fine house on his

upriver estate. The brick mansion, built in the elegant Georgian Style, was sited atop a

fifty – foot bluff commanding a vast sweep of the Hudson – three quarters of a

mile wide at this point – with the mighty peaks of the Catskills forming a dramatic

backdrop. The house became Clarmont the name by which it is known today as a National

Historic Landmark. Robert became know as " Robert of Clermont," an appellation

devised to distinguish this Robert from the five other members of the family who in 1730

shared his name.

For his oldest son, Robert, Philip replicated his own preparation for manor

proprietorship. He firmly believed and adhered to the rule of primogeniture in that his

five younger sons would not share in the manor inheritance, but must be educated to fend

for themselves. Son Robert attended school at New Rochelle just long enough to master the

basics (including business French) and then, in his early twenties, became his

father’s agent in New York. Meanwhile Robert " of Clermont " was bringing

up his only child " to keep an Estate not get one." Robert R. Livingston

commenced the study of law and, unlike his father, showed signs of great promise.

During Philip Livingston’s lifetime, political influence remained a vital

ingredient of financial security in the province of New York so, like his father, Philip

found himself practicing the politics of necessity. As a member of the Governor’s

Council, he exerted a great deal of political power, of which he was as much a slave as

the master. Philip, like his father, found occasional respite from politics by shifting

his focus upriver to the Manor of Livingston, where the economic picture grew brighter

every day. Each year more land was cleared for cultivation more marketable goods were

produced, more quitrents collected and more business done by manor stores and mills. A

large influx of new tenants had been attracted by the size of the leaseholds Philip was

offering – about 170 acres on average, far larger than the corresponding New England

freehold.

All the tenants benefited from the manorial policies of their feudal lord, Philip

Livingston, who expanded the manor’s services and diversified its trading goods.

Philip even concerned himself with the community’s spiritual welfare, building a

church in each new terrant village causing them all to be painted bright red. Paternalism

is not the same as benevolence, and of the latter, Philip Livingston had not a shred.

In 1740, Philip broke ground for his most ambitious project to date, an iron forge near

the eastern boundary of the manor. As the first forge in New York, positioned to

capitalize on the newly opened ore beds in nearby Connecticut, it stood to make an

enormous profit, and Philip’s preoccupation with it verged on obsession. The furnace

took three years to construct.

In the meantime, during the period between 1740 and 1743 the immense Hardenbergh Patent

across the river from the manor had come on the market. Robert of Clermont purchased close

to half a million acres of its prime woodland and choice scenery. His plans for the tract

were a typical combination of the practical and the romantic; they consisted of a grand

Panglasian sweep of hills and valleys, dotted with pretty little model farms on which

happy and prosperous tenants would live in harmony with each other and with their

benevolent lord, himself. In addition to farming their fertile acres, this eager band

would carry out the mining and timbering projects designed to bestow everlasting security

on themselves and vast riches on their master. With this project as lure, and another

round of privateers as security, Robert in 1743 finally turned his back on New York City

and took up full–time residence at Clermont – his dream come true.

Philips’ dream, on the other hand, was faltering badly. His beloved iron forge,

while engrossing more and more of his time, energy and resources, had failed so far to

show a profit. His absorption in it was so great, however, that he too was lured from the

city to establish his base of operations (and his family) on the manor.

Predictably, the brother’s relationship did not benefit from living in close

proximity. Their first squabble arose over water rights to the Roeliff Jansen Kill, the

stream that formed the boundary between their estates. Robert wished to build a gristmill

on the kill, but Philip said that the belonged to him. Consanqrinity, as everyone knows,

tends to turn skirmishes into all out war, and this little spat grew into a legal battle

that persisted over three generations.

By now the proprietor of Livingston Manor had more than one reason to feel testy toward

his younger brother. Robert, having failed to conform to everybody’s dire

predictions, had amassed a comfortable fortune and was supporting himself on Clermont, in

a style to which he had always wished to become accustomed. Adding insult to injury, the

amplitude to his new acreage across the river made Livingston Manor seem positively puny.

Robert’s Hardenbergh land engrossed the whole of Philip’s view: every time he

looked out of his west windows toward the mighty Catskills, everything he saw belonged to

Robert. Finally, Robert, or rather his twenty–four year old only son, Robert R., had

brought off the greatest coup of all: marriage to not just an, but " the " heiress.

She was eighteen-year old Margaret Beekman, daughter of Colonel Henry Beekman, the very

same whose suit to Philip and Robert’s sister, Joanna, had been rejected by their

parents twenty–five years before, and his wife Janet, the daughter of Robert "

the Nephew" Livingston, which meant that the bride and bridegroom were second

cousins, once removed.

Margaret Beekman, as her father’s only surviving child stood to inherit his

portion of the immense Beekman Patent, which lay to the south of Clermont in Dutchess

County. This meant that her children, in turn, Robert of Clermont’s grandchildren,

would eventually go shares in a total of 753,000 acres: Clermont’s 13,000, plus to

500,000 Hardenbergh tract, plus their Beekman mother’s 240,000. It was a mathematical

calculation designed to gall the mind and poison the dreams of Philip, second proprietor

of Livingston Manor.

A French and Indian attack in 1745 on the fort at Saratoga ushered in a new era of

colonial warfare. A raid on Schenectady brought the war very close to the Livingstons at

the manor and Clermont, and the fall of Oswego plunged it right into their pocketbooks.

Philip convinced that Albany would fall and the valley be exposed to the enemy, made plans

to move his family down to New York City, but the Canadians left Albany untouched – perhaps to reciprocate a new policy of neutrality on the part of the Iroquois.

The appointment of James DeLancy, who favored accommodation with the French, as

lieutenant governor of New York, aggravated Philip Livingston’s attack of nerves.

Sitting on the manor, with the military and commercial situation deteriorating around him,

he cannot have been much cheered at the spectacle of his younger brother raking in

proceeds from the war. Robert, together with three of Philip’s own sons, had ventured

once again into privateering and all were realizing huge profits. Although as responsible

citizens they naturally desired the restoration of peace, it is still possible that they

viewed the actual cessation of hostilitions in late 1748 with somewhat mixed emotions.

Phillip’s anxiety about the war, exacerbated by the unmerited good fortune of his

insufferable younger brother, had taken its toll, and no sooner had the peace treaty been

signed than he died at the age of sixty-two, young by Livingston standards.

1749 – 73 Second Generation: Clermont and the Manor

Beginning in 1751 as a minor nuisance, a tenants’ rent strike started on the

eastern end of the manor, near the Massachusetts border. The governor of Massachusetts

officially recognized a group of petitions from Livingston Manor tenants for

Massachusetts’ title to their farms. A boundary dispute had existed for decades

between New York and Massachusetts. The disputed border had been drawn and re-drawn many

times by the contending governments. By 1751 the border claimed by New York was the

Connecticut River and by Massachusetts, a north – south line just twelve miles east

of the Hudson. If the latter should prevail, Livingston Manor would be reduced by half.

Agents of the Massachusetts General Court appeared on the manor and proceeded to lay out

farms on which commonwealth citizens were installed as proprietors. Robert (the

Proprietor) sent men to pull down the houses and eject the interlopers, the New Englanders

returned with reinforcements. Incidents of continued violence increased, and by 1753 a

state of war existed in the eastern manor.

In the spring of 1754 war broke out against the French and Indians in the Ohio valley

and spread quickly eastward to threaten the Hudson. Robert became a principal provisioner

of the colonial troops. An added blessing was that the governments of New York and

Massachusetts facing a common enemy, could no longer afford not to settle their boundary

dispute and began to negotiate the border dispute in earnest. Final settlement took place

in the fall of 1759, at least on paper. The Lords of Trade in London drew a straight north

- south line on the map twenty miles east of the Hudson River and instructed the two

warring colonies to accept it as their mutual border; the line, coinciding precisely with

the eastern border of Livingston Manor.

Robert R. Livingston who had married his cousin, Margaret Beekman, was now in his

mid–forties, a universally esteemed member of New York’s legal and political

fraternity. He currently served in the provincial Assembly with three of his cousins, one

representing the Manor, another the city and county of New York, and a third Dutchess

county. They presented a formidable challenge to the Merchant faction. His legal talents

and reputation were such that he was appointed to the Admiralty Court in 1759 and elevated

four years later to the Supreme Court. In order to distinguish him from all the other

Robert Livingstons, he has always been styled simply " The Judge ".

In April of 1764 the British Parliament in London passed the first of a series of

reform measures designed to clarify and codify the Crown’s relationship with its

American colonies which is, at least, the way the Currency and Sugar Acts were regarded in

London. In America, as we all know, they were viewed quite differently.

Resentment grew warmer still the following year in response to the Stamp and Quartering

Acts. As the date (November 1, 1765) drew near on which the Stamp Act was to take effect,

the Judge and his political allies came together with the popular leadership to organize

the Stamp Act Congress, which met in New York in October. Attended by delegates from nine

of the thirteen colonies, the Congress had no legal standing in the eyes of Great Britain.

Still, its impeccable parliamentary conduct, achieved by the conservative majority and the

elevated style of its address to the King, penned largely by Judge Livingston, lent a

modicum of legitimacy.

Rioting became almost a way of life in New York during the following months, even

years, as each new piece of parliamentary legislation was proclaimed. Nevertheless, ten

years of rioting, of addresses to the King, of burnings in effigy, of parliamentary

bumbling and misunderstanding, had taken their toll.

By 1774 positions in the struggle had hardened on both sides of the Atlantic. As open

conflict with the mother country appeared more and more inevitable, the infighting among

the political parties of New York became less and less relevant.

The Livingstons were not the only Colonial American family with members on opposite

sides of the Revolutionary fence. Even the family’s most celebrated Whigs, Judge

Robert R. Livingston and his son Robert R. Jr., tried to straddle the fence for as long as

possible, and when they did jump, it was with great reluctance and profound misgivings.

But despite their misgivings, despite division within the family ranks, despite

eventual fear for their very lives, the Livingstons who took their stand, stood tall. The

Judge and his cousin Philip labored over the months and years to modulate and legitimize

the course of the resistance. Now approaching their sixth decade of life, they watched,

advised and cheered on the next generation.

1773 – 83 Third Generation: The Reluctant Revolutionary

On the nineteenth of April 1775 British troops engaged fire with Massachusetts

Minutemen at Concord and Lexington, men died on both sides, and the war was on.

The Loyalist interests in the colonial Assembly had managed to block the appointment of

New York delegates to the Second Continental Congress, which was scheduled to convene in

Philadelphia within the month. So the Whigs bypassed the Assembly and invented yet another

extralegal body to serve its purposes. The New York Provisional Convention went into

session on the morning of April 21, selected twelve congressional delegates, and dissolved

itself by afternoon. Three of the twelve chosen to go to Philadelphia were Philip

Livingston, the Manor proprietor’s brother, James Duane, the proprietor’s

son-in-law, and their young cousin on Clermont, Robert R. Livingston, Jr., the

Judge’s son.

All three Livingston delegates entered Congress with extreme ambivalence concerning its

crucial topic, American independence. But if the Manor and Clermont Livingstons were

equally ambivalent at this stage concerning independence, they diverged dramatically in

their expectations for the immediate future. In 1775 both the manor proprietor and the

Judge constructed new mills: the manor’s was for grain, Clermont’s for

gunpowder.

In May of 1776 on his return to Philadelphia, Robert was appointed to the committee to

draft declaration justifying America’s independence in the eyes of the world.

However, his lack of involvement in the actual writing of the Declaration of Independence

was very frustrating. Overshadowed by Jefferson, Adams and Franklin, he contributed not a

single word to the document that was submitted to Congress. Furthermore, on July 2nd,

when Congress finally voted to declare American independence, it did so without the

assenting vote of the delegation from the state of New York, which was forced to abstain.

Congress spent two days debating and amending Jefferson’s text. July 4 is the date on

which it went to the printer. After the New York Convention ratified the Declaration two

weeks later, the vote was retroactively ruled unanimous. Robert was unable to return to

Philadelphia in time to sign the Declaration, which took place on Aug. 2nd. His

cousin Philip was there to give the Livingston seal of approval, and he is known in the

family to this day as " Philip the Signer".

In the fall of 1776, Robert R. Livingston Jr. started and spent much of the ensuing

winter in Fishkill laboring with the committee to draft a state constitution. The New York

State constitution was submitted to the Convention in March of 1777. A predictably

conservative document (penned largely by John Jay, with Robert’s assistance), it won

almost unanimous approval, but was considered far too radical for his cousin, Peter R. of

the manor, whose new fledged ultraconservatism led him to cast the only Nay vote.

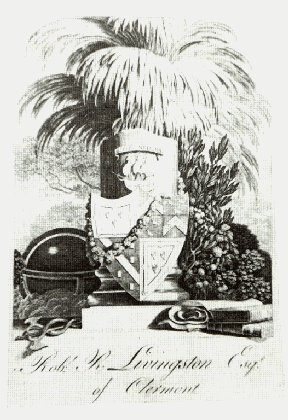

Robert was appointed Chancellor of New York, the state’s highest legal office,

second in precedence only to the governorship. The title of Chancellor pleased him

enormously; he employed it to the end of his life, (even after resigning in 1801 to become

minister to France) and is known by is still. On the same day as his appointment his old

friend and now cousin-in-law, John Jay (who was married in 1774 to Sarah Livingston, the

daughter of New Jersey Governor William Livingston) was made chief justice of the state

Supreme Court.

During the War of Independence three of the Manor proprietor’s sons had built

houses on Livingston Manor. In the decades following more than a dozen mansions were built

by members of the family along a twenty mile stretch of the Hudson’s eastern shore,

over half of them by Robert’s sisters and brothers.

Two hundred years ago the Livingstons owned most of the Catskill Mountains. From the

parlor windows of their river mansions they could survey their half million acre alpine

asset across a broad river dotted with hundreds of sails, many of them Livingston sails.

Their descendants gaze through the same windows at the mountains that belong to others and

a river that America has passed by. A lone oil tanker making its silent, ponderous way up

to Albany is an event, something to call the children to the window for. The Hudson

finally looks like what it always was, a dead end.

Dead end or not, " Livingston Valley" is about all the family has to mark its

historical place in the world. The Livingstons’ territorial sense, rooted in time, is

rare nowadays, and modern history has not been benign to such sensibilities. Caught

between past and future, the " Lords of the Manor" frequently stumble and fall

over the present. But always their goal is the same: preservation of the two vital

elements that make them what they are, the Family and the Land.

Bibliography

Birmingham, Stephen - America's Secret Aristocracy - Little,

Brown & Co., 1987

Lacey, Rober - Aristocrats - :Little, Brown & Co., 1983

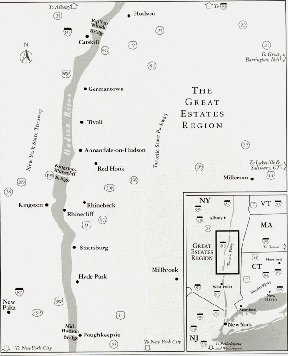

Smith, McKelden - The Great Estates Region of the Hudson River

Valley - Historic Hudson Valley Press, 1998

Clermont House and

Livingston Coat of Arms

1997 Shows part

of the 1920's renovation

Chancellor

Livingston's Bookplate

Livingston's Scottish Arms

Pen and ink 14 Sept

1796 depicts Clermont

rebuilt after the other house

was burned by the British

in the Revolution.

|