|

4:00 P.M.

December 18, 2003

Apiarian

Pertaining to Bees or to

The Keeping and Care of Bees

by Edgar F. Losee

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Edgar F. Losee was born in 1930, in

Houston, Texas. His family moved to Monrovia, California, when he was six years old. He

was graduated from Monrovia-Arcadia-Duarte High School (known today as Monrovia-Duarte

High School). In his senior year he was elected student body president, Boys State

representative, and selected as All - League guard in football.

He attended the University of Redlands

for two years before enlisting in the United States Air Force. His four years of service

included action in the Korean War as a gunner on a B-29 bomber. Following his discharge,

he returned to Redlands, married Bonnie Chambers, and completed his work for a B. A.

degree at the same university.

Upon his graduation he was hired by the

Redlands Unified School District. He served the district for thirty-two years as a

teacher, principal, curriculum coordinator, and assistant superintendent of educational

services.

After the death of his wife Bonnie, he

remarried. He and his wife Bettie have eight children between them; four are his and four

are hers. Ed and Bettie enjoy retirement for it provides many opportunities to pursue his

hobbies of gardening, reading, golf, and travel.

Since retirement, Ed has served in many

organizations which make Redlands such a special place to live. He has been a board member

and president of Family Service; a trustee, president, and docent at Kimberly Crest; a

member of the Adult Correctional Advisory Council, and a starter for the public races

during the Redlands Bicycle Classic. He is a member of the Redlands Country Club and a

member of the Redlands Fortnightly Club.

SUMMARY

The author shares his experiences and

the knowledge gained from his eleven- year association with bee keeping.

The paper describes the four species of

bees that constitute the genus Apis Mellefera, the honey bee, but focuses on the Italian

strain which is the most popular strain in the United States. Mr. Losee also includes

remarks about the African strain that has gained the reputation of "killer

bees."

You will visit the honeybee colony and

learn about the three classes of honeybees and their division of labor: the queen which

lays the eggs; the worker which gathers the food and cares for the young; the drones which

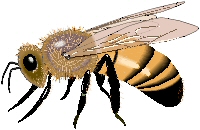

fertilize the queen. There is also a detailed illustration of the worker bee's intricate

body.

The subject of communication among the

bees is covered. It is explained how the queen's message is carried and how the bees

"dance" to announce the location of a source of honey.

The paper includes information about

two of the most serious diseases with which the beekeeper must contend, American Foulbrood

and the Varroa Mite. In addition to the disease information, the author provides data on

the pests and predators that create problems for the bees.

In closing there is some general

information about honey and a description of how honey is harvested and processed.

Glossary

Apiary: the sum total of colonies and hives

assembled on one site for bee keeping operations

Apiculture: the science and art of raising

honeybees

Bee brush: a wooden-handles brush with long, soft

bristles used to gently remove bees from places a beekeeper does not want them to be

Bee dance: the patterned motions by which bees

communicate tactilely

Bee veil: a cloth or wire veil worn by the

beekeeper to protect the head

Brood: eggs, larvae and developing immature bees

Colony: a group of related bees that live together

in a hive or another dwelling as a unit

Drone: a male bee

Extracting honey: removing honey from combs by

means of a centrifugal force machine called an extractor

Frame: the supporting structure for the honeycomb

within the hive

Guard

bees: worker bees that stand at the colony’s entrance and watch for intruders

Hive: the wooden box and its parts in which the

bees live

Hive tool: a short prying tool used to open the

hive, pry frames, clean the hive, etc.

Nuptial flight: the flight the queen makes to mate

with drones

Propolis: a glue-like substance manufactured by

bees from plant resins, used by the bees to seal up the inside of the hive; also known as

bee glue

Queen: the fertile female bee that lays eggs from

which all the bees in the colony will be produced

Queen cell: a peanut-shaped cell, larger than

those in which worker bees or drones develop, in which the queen pupates

Royal

jelly: the highly nutritious glandular secretion of young bees fed to the queen and

the very young brood

Robbing:

the stealing of honey or nectar from a hive by worker bees from other colonies - robbing

bees are usually aggressive.

Smoker: a hand-held firebox attached to bellows

that is used to generate the smoke that

quiets the bees as the bee keeper works with them

Super: a hive body in which bees store surplus

honey, so called because it is placed over or above the brood chamber

Supersedure: the natural replacement by a young

queen of the hive queen (her mother)

Swarm: a group of bees with a queen that has split

away from a colony to fly off and establish itself in a new home; a natural method of

propagation of the honeybee colony

Uncapping knife: a knife used to remove the

capping from the combs of sealed honey for the purpose of extraction; knives are usually

heated by electricity

Wax glands: eight glands of the honeybee that

secrete beeswax

One day in

the spring of 1940, my father called me out to our backyard to see his latest purchase.

Over in the far corner of our property sat a beehive. I could tell he was excited about

his purchase and the thought of having his own bees.

I must admit

the idea had me buzzing also. What were we going to do with a box of bees? Dad was great

at getting involved in new projects, but I was often the one to do the work. For example,

take the chickens and turkeys he bought. It was my job to feed and water them, collect the

eggs, clean the coops, and kill and dress the fryers. Would he be expecting me to become a

beekeeper? Left up to me, I surely could find a better hobby! That evening he told me

there was a great deal to learn about the fascinating life of bees, but not to worry, for

he had already subscribed to a bee-keeping magazine.

Within the

next few weeks Dad ordered some basic equipment from Sears. I was surprised that the

number of items to get started was rather minimal. The basics consisted of two veils,

(that told me something!), a hive tool, a bee brush, and two extra hives with frames and

foundations. The extra hives Dad called “supers.” This meant a hive body in

which the bees stored surplus honey, so called because it was placed over or above the

brood chamber.

I did not

realize then how interested and involved I would become with these social insects and what

an important part of my life they would play over the next eleven years. My father and I

learned about the bees together. In addition to working with our colony and reading the

beekeeper’s magazine, we occasionally worked with Joe Mayer, the owner of Honeyville,

a store on Route 66 in Duarte, California. Mr. Mayer was an authority on bees. He and his

sons operated one of the biggest apiaries in Southern California at that time.

The first

year with the bees went smoothly. We learned about managing the bees throughout the

seasons and picking up on practices that would bring optimum honey production. I also

learned that if you keep bees, you are going to get stung occasionally. Two more colonies

were added that first year. The following year an agreement with the city of Monrovia took

us out of the hobby category into the commercial business.

The police

chief of Monrovia was a neighbor and good friend of the family. One day he asked my father

if he would be interested in handling the swarming bee calls his office received.

Dad’s answer was affirmative. In what seemed like over-night, we were in the

bee-keeping business.

The subject

of my paper today deals with what I learned about bees and bee keeping in those years that

followed that fueled my continued interest in the subject.

Strains of Bees

The

encyclopedia defines the honeybee as any bee of the Apidae family; more strictly, one of

the four species constituting the genus Apis. The term is usually applied to one species,

the domestic honeybee, also know as the European domestic or western honeybee.

All of our

bees were of the Italian strain – Apis Mellefera Ligustica, the most popular strain

in North America. It has been said that in the United States, commercial bee keeping, as

we know it, would not exist without the Italian honeybee. The Apis Mellefera has a number

of varieties throughout the world; however, only four have been used in the United States

with various degrees of success.

Because I am

more familiar with the Italian bees, for the purpose of this paper, I will just mention

the other three strains and focus on the Italian strain.

The Alpine bee, Apis Mellefera carnica Pollman, is native to

the Austrian/Yugoslavian Alps. It is gray-brown in color, very gentle, but requires a lot

of attention.

The

Apis Mellifera caucasica is a gray to black bee that evolved in the Caucasus Mountains.

This bee is rather placid and is considered the gentlest of bees.

The third Apis Mellifera is the old

German brown bee. This variety is not as productive, manageable, or as hardy as the other

strains.

Back to the

Italians. These bees are a bit smaller than the German bee with yellow bands on their

bodies and yellowish hair. This strain is usually calm and gentle, although this trait can

be variable. They have a strong disposition to breeding but are also notorious for

robbing. I had one really bad experience with robbing. One weekend in the upper desert,

two of my high school pals were helping me remove honey from our colonies. We got a bit

careless and allowed honey to drip on the bed of the truck as we were loading the supers.

In no time at all we were in the midst of aggressive robbing bees. We had no alternative

but to quickly wrap things up and make a hasty retreat. My father wasn’t very happy

that the job was not completed and would require another trip to the desert to finish.

Before I

leave the subject of the various strains of bees, I would be remiss if I did not mention

the Africanized variety. In 1956-57 researchers in Brazil imported the African strain of

honeybee for hybridization studies. They were crossbred with European bees to increase

their resistance to heat and humidity. Despite careful handling, some colonies were freed

and began interbreeding with the native strain. Swarms of the hybrid bee produced by the

African/European mix moved out of Brazil, migrating north at the rate of 100-300 miles a

year. By the late 1980s, the Africanized, or killer bee, arrived in southwest Texas.

In 1999 the

killer bees created quite a buzz in the media when they arrived in Southern California.

They quickly gained a “killer” reputation with stories of children and animals

being severely stung in seemingly unprovoked attacks.

The

Africanized honeybees are smaller and more resilient than the common European bee. They

are also more territorial. They exploit a wide variety of food and water sources and

out-forage their relatives. An Africanized worker bee reportedly forages herself to death

in only two weeks compared to five or six weeks for a European strain.

Honey

production is reportedly outstanding, but harvesting can be a dangerous experience. When a

hive is opened, the bees often erupt from their home in a furious attack. The bees

actually carry less venom than the European honeybees, but they attack in much greater

numbers and are more persistent.

With the

rise in number of this aggressive, defensive and unpredictable Africanized variety, people

should be more aware of bee activity around their property. Unfortunately, there is no

quick and easy technique for easy identification other than the bee’s behavior.

Thanks to our winter rains this year we have had more flowers. More flowers means more

pollen and more bees, including this Africanized or “killer bee” variety. While

a small number of foraging bees is little reason for concern, a swarm or nest near your

residence could be trouble. I would urge you to leave the bees alone and call Vector

Control or a pest control company. Let the professionals handle the situation.

THE HONEYBEE COLONY

Each colony

includes three classes of honeybees:

1. The queen which lays eggs

2. The workers which gather food and care

for the young

3. The drones which fertilize the queen

The queen

bee lays the eggs that hatch into thousands of workers. Laying eggs is the queen’s

only job. She doesn’t gather food or help build the nest; in fact, the workers feed

and groom her. The queen bee does not rule the colony, but she is the force that keeps it

together. The workers become excited and disorganized if her presence is not sensed in the

hive. When a queen is ready to look for a mate, she makes herself known to the drones and

leaves the hive flying high into the air. The drones follow, but only the swiftest and

strongest ones finally catch and mate with her. After mating, the queen returns to the

hive. Within a few days she begins to lay eggs. Usually a queen mates once in a lifetime,

but she will continue laying eggs for the rest of her life. A queen may live as long as

five years. She can lay as many as 2000 eggs a day and up to a million in her lifetime.

As long as

the queen lays eggs, the workers pay her the greatest attention. Surrounded by the

workers, the queen walks about the hive, usually at the lowest story of the hive, which is

called the “brood chamber.” The beekeeper places a wire grating, or excluder,

between the brood chamber and the hives above it, which are called supers. The excluder

prevents the queen, due to her larger size, from laying eggs in the honey stored in the

supers.

The

six-sided comb in the hive comes in two sizes. Most of the comb cells are smaller in size

and are used for storing bee bread. Bee bread is a small amount of honey mixed with

pollen. I mention the two sizes of combs, because one of the remarkable things about the

queen’s egg-laying is that she lays one kind of egg in the larger cells and another

in the smaller cells. The eggs look exactly alike but develop into two different kinds of

bee. The workers come from the smaller cells, and the drones emerge from the larger cells.

If the queen lays only two types of eggs, from where does the queen come?

Queen

The queen

comes from the ordinary worker eggs, but the eggs have been treated in a very different

way. From time to time the workers add to the small worker cells making them larger until

they are about the size and shape of a small peanut. As the worker eggs in these cells

grow, the nurses feed them differently from the eggs in the smaller cells. From these

ordinary worker eggs in the peanut-shaped cells, new queens will come. So, queen bees are

made by worker bees.

Every bee,

worker, queen, or drone goes through four growing stages. After the queen lays an egg,

which is stage one in the cell, a nurse bee keeps close watch over it. Just before the egg

hatches, in approximately three days, the nurse adds a small amount of “royal

jelly” to the cell. Scientists are not exactly sure what royal jelly is, but they

believe it comes from glands in a nurse bee’s head.

During the

second stage, or larva stage, the nurse bees continue to attend and feed each tiny larva.

After a few days, the nurses begin to feed most of the larva a combination of nectar and

pollen that has been stored in nearby cells. The larvae in the built-up queen cells

continue to be fed royal jelly, instead of bee bread. Thus it is variance in diet that

makes a queen from an ordinary worker bee.

The cell

with the larva is capped with wax by the worker bees, of course, and the larvae within

begin to make themselves cocoons. When the cocoons are safely sealed in the cells, the

young bees begin their third stage called the pupa. In the cocoon a great change takes

place. The wings, eyes and mouth parts are formed, and the worm-like creature becomes a

complicated bee. As the bee is fully formed, it gnaws its way through the wax and emerges.

Worker Bee

After

twenty-one days from egg to adult, the bee leaves the cocoon with an efficient body and

the instincts of a worker bee. At this point the worker is less than one half inch in

length and weighs approximately 60 milligrams. This worker is small, but within weeks she

will be carrying loads heavier than she is and foraging on flights that may be over a

mile.

A

worker’s life is short especially during the spring and summer, which is the most

active time of foraging. The worker bee seldom lives more than a month when the honey flow

is heavy. Foraging presents many types of danger for the workers, and many do not even

last a month.

At this

point let me direct you to my illustration and point out the details of the worker

bee’s intricate body. (1) The triangular head has three simple eyes on the forehead

and (2) two compound eyes. Color is important to the honeybee, yet the bee does not see

quite the same range and graduation of color man sees. For example the bee cannot focus

its eyes because the eyes have no pupils. (3) The antennae are segmented and supply the

bee with not only a sense of touch but also a sense of smell. Bees have an acute sense of

smell that is far better than ours. Honeybees use chemical substances, especially in the

form of odors, to give information to one another. These chemical substances are called

pheromones and are secreted from one gland in the bee that will bring about a specific

behavioral response in another individual of the same species. (4) Mandibles are used for

holding and in building combs. (5) Set back under the head is the proboscis used for

sipping water and honey. (6) Long spines on the middle legs remove wax from the glands.

Each leg has a claw foot used to cling to flowers and plants. (7) Toward the rear are the

wax scales and, of course as you already know from first hand experience, a barbed

stinger! (8) The rear legs have an assortment of brushes and pollen baskets. (9) The bee

has one pair of wings on each side of the thorax. The front wing of each pair is the

larger. As the bee flies, the wings are coupled together by a tiny row of hooks and act as

one wing. A bee can fly forward, sideways, or backwards, and can hover in one place.

When I first

began working with the bees, my father told me that worker bees had specific tasks they

performed. Some bees were foragers, or nurses, or guards, or house workers, while some

attended the queen.

After

working with the bees and reading about them, I learned that while they do have specific

duties, the tasks performed depend on the stages of bodily development the workers have

reached. For example, researchers have determined the new worker’s first assignment

is “housekeeping;” cleaning the brood cells to make ready for the next eggs.

Somewhere between the tenth and fourteenth days of their lives, worker bees secrete royal

jelly. As already mentioned, this secretion is used to feed the queen and the young brood.

So, a worker is now a nurse bee. After two weeks of development, the hive worker is ready

to venture into the fields in search of nectar or pollen. While some gather nectar and

pollen, others search for water or propolis. Propolis is a glue-like resin material

collected from trees and plants and often called bee glue. One other housekeeping chore is

that of undertaker. The undertaker bee, usually a younger working bee, arrives on a death

scene and performs the task of removing a dead body from the hive.

Drones

The drone,

or male bee, is present in the hive only in the spring and early summer and is of no

concern in the fall, when all but one bee in each colony is of the worker caste. The only

role of drones in the colony is to mate with the queen. Drones are not physically equipped

to collect nectar or pollen, nor can they defend the hive, as they have no stingers. They

are easier to identify because of their larger size. In the hive they tend to hang

together in groups.

Young drones

emerging from their cells feed on honey. Later they learn to solicit food from the

workers. As they reach old age, they apparently lose the ability to feed themselves.

Though they continually try to solicit food from the workers, they are unsuccessful and

soon die of starvation.

Drones

become sexually mature within fourteen days of age. At this time they begin to take short

orientation flights searching for their mates. When drones spot a queen, they fly high in

the sky to mate. A queen might mate several times on her nuptial flight. The drone dies in

the mating process. The genitalia is contained within the drone’s abdomen. In mating

the genitalia and parts of the abdomen are torn loose from the body, and the drone falls

lifeless to the ground.

The worker

bees seem to regard the drones with favor up until the queen has mated. After that, the

drones are no longer needed and become a drain on the hive’s resources. When the

nectar flow declines, the workers ban the drones from the hive. Many a time I observed

drones trying to re-enter the hive only to be turned away by the worker guard bees. The

smaller worker bees will gang up on a drone and repeatedly kick and shove him out of the

hive.

Communication

The whole

fabric of the honeybee society depends upon communication –an instinctive ability to

send and receive messages and encode and decode information. Honeybees in the hive are

confronted with many of the same kinds of problems that humans are confronted with in

their every day lives. They must be able to recognize their queen and one another. They

need to communicate immediate danger and where food can be found. In the hive, these tasks

must be done in an orderly manner.

The queen

communicates by producing a substance that can be obtained from her by direct contact.

This substance evidently stimulates the working behavior in the hive. Whatever attracts or

carries the message has simply been called “queen substance.” To

“tell” each other where nectar and pollen may be found, the worker bees have

developed two kinds of dance, a round dance and a tail-wagging dance. Each dance is

performed on the vertical surface of the honeycomb. I will do my best to describe the two

dances for you.

The round

dance is the simpler of the two dances. Upon returning to the hive, the forager will

regurgitate a drop of nectar to announce a source for honey located near the hive. The bee

then whirls around in one place while the surrounding bees use their feelers to pick up

the flower’s scent clinging to the bee’s body.

The

tail-wagging dance is more complicated and tells the bees the nectar source is a greater

distance from the hive. In this dance the bee makes a flat figure eight with a straight

line between the loops. This line serves as a pointer in that it tells the other bees how

far right or left of the sun to fly upon leaving the hive. The bee does this by laying out

the “8” on the comb in such a way as to locate the sun at the top, regardless of

where the sun really is in the sky. The bee then makes a run at an angle from this

imaginary sun. The bees comprehend this angle and apply it as they search for the nectar.

The tail wagging tells the bees where to fly in relation to the position of the sun. Thus

it is that the other bees are able to make a “beeline” to a newly discovered

nectar source that may be a mile or more distant from the hive.

As a young

teenager I had the opportunity to observe these dances through a glass-covered hive that

was located inside the Honeyville Store in Duarte, that I mentioned earlier. The store

sold only honey and beeswax but had displays that gave information to customers about the

life of a honeybee.

The language

of the bees seems unbelievable, yet it has been confirmed by scientific experiments

numerous times. There is no doubt the bees understand the language, as long as it is

introduced into a hive of the same kind of bees. Each distinct species and geographical

race possesses its own dialect. But this subject is beyond the scope of what we needed to

know to raise bees.

Diseases and Predators

For the

beekeeper, in addition to the manipulation of his bees to enable them to produce more

honey than they need, he must also maintain the hive by protecting the colony against

diseases and predators. For the purpose of this paper, I will only mention two of the most

serious diseases about which a beekeeper must be concerned.

Of the

number of bee diseases that can have a debilitating effect on the hive, none is more

serious than American Foulbrood. It is a disease caused by a strain of bacteria that

infects the bee larvae and kills them in the pupa stage.

There are

two problems with Foulbrood that make it difficult to control. First is that the bacteria

can enter a spore in which it can live for years. A second problem is that the bacteria

reduce the dead pupae to sticky globs that are difficult for the bees to remove from the

hive. It is also easy to contaminate one’s hands or a hive tool with the disease and

transfer the disease to another hive.

At the time

we had our bees, the treatment for American Foulbrood was to destroy the infected colonies

by burning them. A state apiary inspector usually handled this job. In the last years of

our bee-keeping experiences, we had twenty hives destroyed because of Foulbrood. It was

hard to watch years of investment in time and money being reduced to ashes.

Foulbrood

can be prevented by medicating bees beforehand; it cannot be cured once they have it. I

have read that the seasonal application of Terramycin has proven to be a good control. The

beekeeper can mix the drug with confectionery sugar and dust the brood comb with it or

feed the bees a sugar syrup with the drug dissolved therein.

Another

threat is the Varroa Mite, a parasite of the Asian honeybee, discovered in the United

States in the late 1980s. The mating female mites that are about to lay eggs move into

cells containing larvae just before the cells are capped. The mites immerse themselves and

feed on the larval food that is there. When the young mite larvae have finished this food,

they start to produce eggs that hatch. The young as well as the old female mites pierce

the membrane of the bee larva, now turned pupa, and feed on its blood. If too many mites

are present, the bee will die. If there are only a few mites, the bee may continue to

develop. But when it emerges from its cell, it usually has a short life span or is somehow

maimed. With fewer bees and underdeveloped bees, the colony becomes severely weakened.

Many

chemicals have been tested for Varroa control. Several compounds have been affective,

being non-toxic to the honeybee and toxic to the mites. Though the Varroa Mite causes a

most serious disease to the European honeybee, the Asian and Africanized bees protect

themselves from the Varroa Mites through grooming. These bees bite the mites and remove

them from the hive. The mites are present in the hive, but with a reduction in number,

they are kept from being a serious problem.

There are a

number of other honeybee diseases, but I have elected to forego discussing them in this

paper. Suffice it to say there are control methods for most of the problems. The important

thing for the beekeeper is to be alert and able to diagnose problems early, while the

colony is strong enough to survive.

In addition

to the diseases there are a number of pests and predators a beekeeper must contend with,

depending on the location of the apiary. One pest is mice. Mice are a nuisance. Mice will

nest in stored combs and in hives containing bees. It is an interesting fact that mice can

successfully build a nest within a hive. This is usually done during the winter months

when the bees are not as active.

In the

wooded or mountainous areas, bears will sometimes attack beehives and do tremendous

damage. Unfortunately there is little you can do to protect against damage by bears.

Skunks can

be a serious problem for the beekeeper. The skunk will scratch at the hive entrance. As

the bees crawl out to protect their home, the skunk will eat them. It is difficult to

control attacks by skunks, and weaker hives are often decimated. The skunks’

continuous feeding can also irritate the bees and keep them in a constant state of alarm.

The end result is that the bees get more aggressive and are more difficult to handle.

There is a

wax moth that will enter a hive, usually at dusk, and deposit its eggs. In the weaker

colonies, the wax moth larvae will reduce the comb to nothing but a tangled web.

Moving away

from the problems and back to the years prior to 1946, we continued to collect swarms and

add to our apiary. When we reached eighty colonies, we decided that was all we could

handle. From the beginning, we had purchased all of the bee-keeping equipment and

assembled it ourselves. We had built and painted hives and had assembled the frames as

well. Over the years we selected four locations for the apiary. Two spots were in the

Covina area, and two were in the upper desert - near Hesperia and the other near the

little town of Hinkley. The honey flow in the Covina area was orange. In the upper desert

it was alfalfa honey flavored with a hint of white sage and eucalyptus.

The trips to

our apiary in the upper desert were often an adventure. Hauling bees/honey over Cajon Pass

in the early 1940’s could be a challenge in our old truck. There is one drive I shall

never forget.

We were on

our way to take care of our bees in Hinckley early one morning and passed a terrible

accident involving a semi-truck. We learned later that the truck driver had lost his

brakes near the summit. He had stayed with the run-away truck most of the way down the

grade before jumping to his death.

After he

jumped, the driverless truck crossed from the south-bound lane, cut across the north-bound

lane, and crashed into a two story building. The first story of the building was totally

destroyed, but amazingly, the sleeping occupants on the second floor escaped unharmed!

Months later I read about it in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not article.

In our third

year of the bee-keeping venture, we bought a small manually operated extractor. We had our

own labels printed and sold our honey in one or two pound jars. Three years later we were

using a twenty-frame extractor and sold the honey to the Superior Honey Company in

Alhambra. The honey was sold in five-gallon metal cans, each weighing approximately 60

lbs.

Honey

I thought I

would conclude this paper on honeybees with a few words about honey. This natural product

has played an important role in human nutrition since ancient times. Up until about 250

years ago, it was the sole sweetening agent. In the sixteenth century as the Europeans

were bringing honey bees to America, trade in Caribbean sugar cane introduced the world to

another sweetener, sugar.

There are,

quite simply, almost as many types of honey as there are flowers. Knowing my interests in

honey, a few close friends are always bringing me a new flavor to sample; a lavender from

France, a mountain fireweed from Oregon, to name a few.

As a

foraging bee makes its rounds sucking up nectar, the nectar is taken into a honey sac

where it undergoes a change. The nectar is changed by juices that come from glands, just

as saliva comes from glands in your mouth. When the field bee returns to the hive, she

gives her nectar to a house bee. The house bee spends some of her time squeezing the

nectar in and out of her own honey sac, and rolling it around her tongue. During this

process, some of the moisture is removed from the nectar and enzymes from the house

bee’s glands are added.

In the next

step of the process, the house bee looks for a cell in the comb where she can store the

honey. Finding an empty cell, she forces the honey out of her sac. When the cell is full,

the honey is quite thin and moisture needs to be removed. To remove the moisture, the bees

fan their wings to circulate the air. Once enough moisture is removed and the honey is

thick enough, the workers cover the cells with wax. Once capped in the comb, the finished

product is imperishable.

To remove or

harvest the honey, the beekeeper removes the super with the capped frames from the hive.

The bees are removed from the frames by gently shaking the frames and using a bee brush or

using a fume board saturated with a chemical substance that repels the bees. Years ago we

used carbolic acid on our fume boards – a practice that is not approved today by the

Environmental Protection Agency. Repellents are effective in harvesting honey because bees

are not disturbed as much.

Next is the

extracting process that involves three basic steps: uncapping the combs; placing the combs

in an extractor machine to remove the honey; and straining the honey to remove bits of wax

or extraneous material.

California

is one of the top- producing states in honey production. Not too long ago, I read that

honey production has been down for the past two years, but bee- keepers are receiving

about twice as much money for the product.

Honey ranges

in color from white through dark amber. The lighter-colored honeys have a milder flavor,

and the dark honeys have a stronger flavor. Clover and orange honey are the most popular.

Comb honey is very popular with the public, as is the new trend of flavor-infused honey.

Infused honey is made by adding a flavoring ingredient such as mint, ginger-lime, or

rosemary to the honey. Then it is heated and strained.

In closing,

you might think the bee colony is a totalitarian government, a matriarchy with the worker

bees as mere workers. Today, however, after years of scientific experiments, we know that

is not the case. The beehive is a remarkable society. It is a strange dictatorship where

the queen is vote-less and the ruled have equal votes. It appears the honeybees have

developed into a well-nigh-utopian insect society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Butler and

Colin, The World of the Honeybee.

New

York: Taplinger (1975)

Dandant and

Sons, The Hive and the Honeybee.

Hamilton,

Illinois, Dandant and Sons (1976)

Morse, R.A., ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture.

40th

Edition A.I. Root Co. Medina, Ohio (1990)

Morse, R.A., The New Complete Guide to Beekeeping.

Countryman

Press, Woodstock, Vermont (1994)

Taylor,

Richard, The Joy of Beekeeping.

St.

Martin’s Press, New York (1974

|