|

MEETING #1641

4:00 P.M.

November 30, 2000

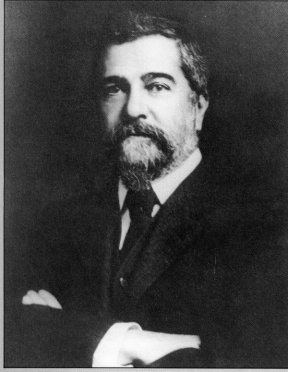

L. C. T. American Icon and Iconoclast

by Stanley D. Korfmacher M.D.

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public

Library

SUMMARY

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the primary exponent of Art Nouveau in America. This

brief biography includes his major achievements in Painting, design art glass, stained

glass windows, mosaics, metalwork, enamels and architecture.

BACKGROUND OF THE AUTHOR

Though not a graduate gemologist, Stanley D. Korfmacher

M.D. has studied gems and minerals well over twenty years. He has subscribed to Gems and

Gemology, the respected GIA publication, for twenty years.

He was born on December 7, 1931, in Grinell, Iowa. His

father was Edwin Korfmacher M.D., F.A.C.S. and his mother was a registered nurse.

He graduated from Carleton College in 1953 and from

Northwestern Medical School in 1957. Subsequent training included internship at Swedish

Hospital in Seattle, and the Lahey Clinic in Boston from 1958 to 1961. From 1961 to 1963

he served as a physician with the U.S. Public Health Service. He was Assistant Chief of

Medicine at San Francisco Marine Hospital.

As a specialist in internal medicine he practiced at

the Beaver Medical Clinic in Redlands, California, from 1963 to 1994.

Some know him as an antiquarian, classical clarinetist,

mineral collector, art collector (especially art glass and Art Nouveau), auto buff, and

owner of three dogs. He was a founding member and 1st clarinetist in the Fourth of July

Band for 16 years. He is the Chairman of the Redlands Cultural Arts Commission,

Past-President of the Spinet Music Club, and is on the Boards of the Redlands Symphony,

and the Redlands Conservancy.

For 14 years he has been one of the supervisors of the

Medical Museum of the San Bernardino County Medical Society and he heads that subcommittee

of the Historical Committee.

L. C. T. American Icon and Iconoclast

In the 1880’s a worldwide movement began which was

nothing less than a revolution in almost all areas of art and design, from jewelry to

architecture. Inspired by the simple beauty and curvaceous forms of Japanese,

Celtic, Viking and Islamic art and of plant and animal life (including the human female!),

artists produced dazzling new works of painting and illustration, sculpture, metalwork,

art glass, ceramics, pottery, textiles, furniture, and architecture. In revolt

against decades of classical revival sameness in painting and sculpture and Victorian

excess in architecture and design the new art forms swept across Europe. The

movement was called Art Nouveau in Belgium and France, Secession in Austria, Jugendstil

(youthful style) in Germany, Modernismo in Spain and Stile Liberty in Italy (after an

English designer, Arthur Liberty, and his firm making jewelry and household wares with

excellent designs in the new style).

Of all the designers who brought Art Nouveau to America,

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the earliest, and by far the most important in nearly all of the

visual arts and crafts. In architecture, Louis Sullivan, H.H. Richardson and Frank

Lloyd Wright were the prominent representatives of the new style, although Tiffany also

dabbled in architecture.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was born into a wealthy merchant

family in 1848. His father, Charles Lewis Tiffany, was the founder of the legendary

New York store selling beautiful and exotic wares from around the world. He had been

the manager of the family general store in Connecticut since age 15. At age 25 in 1837 he

moved to New York to start a business with a school friend, John Young. The modest

stationery and fancy goods store featured unusual and beautiful window displays by Charles

Tiffany and the business thrived. The partners traveled to Europe seeking out

supplies of Dresden porcelain, Bohemian glass, French clocks and diamonds.

Charles’ great love was jewelry. In 1848

revolutionary upheavals in Europe allowed Charles to buy diamonds from the fabulous

collection of the Hungarian Prince Esterhazy and at the French Government sales he bought

24 lots of diamonds including jewels of Marie Antoinette and Louis XV. Louis Comfort

Tiffany was born that same year, when Tiffany and Co. had become a jewelry shop for

millionaires.

Charles had married Harriet Young of Connecticut, his

partner’s sister. Louis was her third son; her first boy died at

age 3 and the second before he was a year old, so it is likely that Louis was doted

on. However, he is described as solitary, dreamy, willful, proud and

capricious. His two sisters and younger brother were no match for him and he proved

too disruptive for his strict mother to tolerate so he was sent to boarding school and

then to a military academy.

When the Civil War broke out. Charles Tiffany

transformed his elegant showrooms into a military depot. Tiffany and Co. supplied

and manufactured swords, rifles, boots, caps, medals insignia, and even ambulances. Charles Tiffany became a wealthy man.

Both before the war as a child, and after as a young man,

Louis was a regular visitor to the Tiffany workshops and was greatly influenced by the

artisans and their work. A master silversmith, Edward C. Moore was especially

important; he had worked for Tiffany and Co. since 1851. His artistic tastes were

not European but Islamic, Persian and Japanese. He influenced a generation of New

York artists and craftsmen. He collected objects d’ art and young Louis was

entranced by his splendid collection of Oriental and antique glass.

Louis left school in1866 and announced his intention to be

an artist. With his great wealth he could have been a playboy but became a serious

art student. He avoided formal classes but roamed Manhattan sketching and often

visited the studio of painter George Inness who took him on as his first and only

student. Tiffany’s output was prodigious and aroused both respect and envy, for

he was a fine painter. Within a year, in1867, the National Academy of Design in New

York exhibited his painting “Afternoon”.

The following year found him in Paris, studying with Leon

Bailly. He then toured Spain and North Africa with Samuel Colman, another young

American painter, and his work that year showed talent in architectural drawing.

Everywhere he went he sketched and observed. Islamic domes and arches, interiors,

lamps and intricate decorations would all show up in his later work.

Tiffany returned to New York and produced paintings such

as “Mosque and Market Place”, “Ruins of Tangiers”, “View of the

Nile” and “The Snake Charmer” which were highly regarded. He began to

paint in a technique closer to Impressionism and introduced that style to the American

Watercolor Society which had been founded by his friend, Samuel Colman. In 1875, at

age 27, he painted “Duane Street”, a city slum, anticipating the American Ashcan

School of 1908, the aim of which was “to found an American Art based on a realistic

portrayal of the contemporary scene”.

He exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876 and

the 1878 Paris Exposition as well as the National Academy of Design. He helped found

the Society of American Artists of which he was treasurer and which included George Inness

and John LaFarge.

Tiffany had married Mary Goddard in 1872. Their

first child was born the following year but Mary lost her second baby and contracted

tuberculosis in 1874; her health remained permanently impaired.

In 1874 Tiffany experimented with photography. One

of his biographers, Gertrude Speenburgh, claims that he was the first to take

“instantaneous” pictures of birds and animals.

In 1875 he started experiments in glass and in 1878

established a glass-making house of his own. That same year he traveled to the Paris

Exposition with his old mentor, the silversmith Edward Moore, who won the gold

medal. They met Siegfried Bing who would later introduce Tiffany’s glass

works to Europe. At the same exposition, Louis’ father, Charles was created a

Chevalier de la Legion d’ Honneur.

Back in New York Louis and his Associated Artists were

commissioned to decorate a new theater. His work was so admired that it led to work

decorating a mansion and a Veteran’s Room and Library at a New York armory. Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) commissioned him to decorate his house in Hartford,

Connecticut.

Meanwhile, Tiffany’s glassworks had burned down

twice, but he continued his experiments at the Heidt Glasshouse in Brooklyn and patented a

new colored window glass. In 1882 the Associated Artists were commissioned to

decorate the Vanderbilt home and the White House. Chester Arthur had refused to

move into the White House after the death of President Garfield claiming the place looked

like “a badly kept barracks”. Tiffany redecorated the Dining Room, East

Room, Red Parlor and Blue Parlor. His piece de resistance was a floor to ceiling

opalescent glass screen with interlaced eagles and flags. (When Theodore Roosevelt

moved in in 1902 he instructed the architect to demolish it!) He had finished the

redecoration, which also included large mosaics, and huge chandeliers, in an amazing seven

weeks. He was overextended, and broke off from Associated Artists. His next

important commission was for the new Lyceum Theater auditorium, the first to be completely

lighted by electricity. His work was well received, but the theater failed and

Tiffany was not paid. He was forced to sue and ended up owning the theater!

In 1883 Louis and Mary went to Florida in hopes of

improving her health but she died the following year after a ten-year battle with

tuberculosis. To divert his son from the loss of his wife and the theater disaster,

Charles Tiffany had him design and decorate a new mansion for the entire family at 72nd St. and Madison Avenue. Louis designed the most lavish penthouse suite for

himself. The main room featured a large curvilinear quadruple fireplace with a

single chimney resembling a large tree. This was the first example of American Art

Nouveau.

Louis remarried in 1886 giving a mother to his three small

children and a more settled life. Louise Knox was a maturing influence and Louis

turned to his father’s example to redirect his professional life. In the next

four years, Louise bore twin daughters and a third daughter who died as a young

child. Louise was the daughter of a well- known clergyman and this led to many

ecclesiastical commissions. Churches across the United States featured large Tiffany

stained glass windows depicting Biblical scenes or landscapes; the landscapes were a

breakthrough and controversial at the time. There were also memorials and

mausoleums, built entirely by Tiffany craftsmen.

In 1888 he designed the Ponce de Leon Hotel in St.

Augustine, Florida which received high praise from the public and led to many more orders.

In 1889 at the Paris Exposition he saw the remarkable

glasswork of Emile Galle of Nancy, which inspired his own creativity. He also

found that Siegfried Bing would be delighted to represent him in Europe. It was to

be a lucrative relationship for both men.

Much of the credit for the early growth of Art Nouveau

belongs to Siegfrid Bing, a German-born dealer in Paris who served as guru and merchant

for the artists of the new movement. He later set up his own workshop as well.

In 1890 the French government sent Bing to the United

States to survey American art and architecture. His host in New York was Tiffany who

took him around his Fourth Avenue studios and workshops. Bing reported that he saw

“a great art industry, a vast establishment combining under one roof an army of

artisans of all kinds united by a common current of ideas. It is perhaps by the

audacity of such organizations that America will prepare a glorious future for its

industrial arts”.

Bing also saw Tiffany’s work in the Havemeyer mansion

on Fifth Avenue with its lush stained glass and mosaics and famous hanging

staircase. Bing exclaimed “Nothing could achieve such a unified concept in an

interior”.

During this same visit, Bing and Tiffany planned an

amazing project. Bing suggested that he, Bing, commission French artists to submit

paintings to be rendered by Tiffany in stained glass. Ultimately designs were

purchased from Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre Bovard and the windows created in

Tiffany’s New York workshop . They were exhibited to great controversy at the

Salon du Champs-de-Mars. Some critics dismissed them for the incongruity of mixing

the media of paint and glass, but others saw these works as a perfect statement of the Art

Nouveau ethic, blending fine art and applied art and naturalism in decorative form.

Bing displayed these windows and eight other Tiffany windows based on other artists, along

with Tiffany vases when he opened his new gallery, L’ Art Nouveau, at 22 Rue de

Provence in 1895. The gallery name quickly became the dominant and lasting name of

the movement.

The 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago was an

opportunity for Tiffany and many other Art Nouveau artists. He planned to show six

paintings, but Bing persuaded him to do something grander and Tiffany designed a

chapel. Multiple romanesque arches enclosed simple forms with lavish surface

ornament in a light room and a dark room. The former had a mother-of-pearl

chandelier and white marble altar and iridescent white tiles and mosaics; the latter

ranged from light to deep greens and blues with, for example, blue and green mosaic

peacocks set in black marble. Critics and the public praised the work. It was

purchased and donated to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City but

returned to Tiffany in 1916. He set it up in his home, Laurelton Hall, and declared

it a chapel of art, not worship.

Also in 1893, Tiffany acquired his own glass house, the

Corona Furnaces on Long Island. There he worked with Arthur Nash, an English glass

expert who had come to the Unit States the previous year. Tiffany employed him as

both chief designer and manager. Nash stayed with Tiffany for 15 years and brought

his sons into the business. The sons felt that Tiffany never gave their father his

due.

Tiffany produced lamps beginning in 1893. They were

kerosene at first but Tiffany quickly took advantage of the greatly increased design

possibilities of electricity, such as fully enclosed shades, and fixtures which could

direct light in any direction. Tiffany did not originate leaded glass shades but his

shades and bronze lamp bases were marvels of original design and fine workmanship. The

leads were always copper foiled. The bronze was often inlaid with glass or mother of

pearl. His designs were extensively copied both in America and abroad. Lamps

were made up to 36 inches in diameter and cost up to $750, equivalent to about $20,000

today. Most were designed by his employees, but Tiffany patented designs of his own

in 1914 and 1918.

In 1894, Tiffany registered “Favrile” as a

trademark, suggested by Arthur Nash. It was derived from the Old English work

fabrile, meaning “belonging to the craft”. Favrile art glass was

characterized by a silky look and feel and was often opaque or nearly so with bright

colors or metallic sheen or iridescence, alone or in combination. Some were simple

forms with one color, others elaborately decorated in Art Nouveau themes or abstract

organic shapes. Louis Tiffany is seen now as a precursor of Abstract Expressionism,

a specifically American art form which did not peak until the 1950’s.

Incidentally, Tiffany claimed that he checked every item of Favrile glass

personally. The pieces were marked L.C.T. and numbered. Some of the finest

pieces have a full signature. Many,many imperfect pieces must have been destroyed.

According to Koch, Tiffany did not state that he had

invented the means for producing iridescent glass but he did describe the method he used

in the patent claim filed in 1880: “The metallic luster is produced by forming

a film of a metal or its oxides, on or in the glass, either by exposing it to vapors or

gases or by direct application. It may also be produced by corroding the surface of

the glass.” Twenty-dollar gold pieces were put in a heated solution of nitric

acid and hydrochloric acid and a diluted solution was sprayed on the glass before it

cooled producing a satinlike texture. Gold chloride was often suspended in the glass

itself as well, giving a gold surface to meld with the spray.

Iridescent glass had been made a few years earlier in

Bohemia and Venice. Ludwig Lobmeyer exhibited the first to be produced commercially

at an exposition in Vienna in 1873.

Almost the entire first year’s output of

Tiffany’s Corona Furnaces was shipped to top museums in the United States and around

the world – Paris, Berlin and Tokyo. The Smithsonian purchased 38 items, and 56

were presented to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City as the gift of Henry

Havemeyer.

In early 1896 Tiffany felt ready to launch his new product

on the market. He invited the press to his Fourth Avenue studios. The New

York Times called the glass “curious and entirely novel, both in color and

texture”. The Herald called the variety “almost bewildering” while the Commercial Advertiser described the display as “a fine art

museum in itself.”

But the first major public exhibition of Tiffany glass had

actually occurred a few months earlier, at the grand opening of S. Bing’s shop in

Paris, the Salon de l’ Art Nouveau, on December 26, 1895. Twenty pieces of

Tiffany blown glass joined the ten stained glass windows made after paintings by French

artists which Bing had commissioned. There was also glass by Galle, jewelry by Lalique,

furniture by van deVelde, paintings by Bonnard, Roussel and Toulouse-Lautrec (among

others) and prints and drawings by Beardsley and Whistler (among others). L.C.

Tiffany was to be known after this as the foremost American representative of Art Nouveau.

In addition to art glass and the famous lamps so well

known today, Tiffany Studios supplied drapes, textiles, rugs, carpets and furniture.

As the experiments with enamel and inlay were applied to everyday objects, magnificent

desk sets of bronze with enamel, glass or mother-of-pearl appeared, along with jewelry

boxes, tobacco jars, vases, lamp bases etc. Favrile glass came to be used for dinner

services, wine glasses, decanters, cologne bottles and other utilitarian pieces. Tiffany Studios was in mass production.

Meanwhile, Tiffany and Co. was world famous for their

jewelry. Louis designed many expensive pieces using his father’s store of

precious stones. His pieces were unsigned, marked Tiffany and Co. like all the

others, making verification difficult. He favored American gemstones, buying most of

the output of the Montana sapphire mines, using especially the fine, clear cornflower blue

stones from the Yogo Gulch mine, the finest small sapphires the world has ever

produced. He also used tourmaline from Maine and California. When kunzite, a

new gem material, was discovered in California it was identified by Tiffany’s

gemologist, George Frederick Kunz and named for him. Tiffany jewelry featured

semi-abstract designs from natural forms and showed the influence of enamel work from the

Orient, Byzantium and the Italian Renaissance. Faceted gemstones were combined with

glowing enamel, opals, shell, coral or amber; opaque stones such as lapis, onyx and

malachite were also used.

Even more of Tiffany’s income came from stained glass

windows. Church windows, memorials and mausoleums were produced on such a large

scale that Tiffany finally purchased his own granite quarry in Massachusetts.

Jewel-medallion windows were chosen by Stanford White for his Madison Square Presbyterian

Church. These windows were later installed in the Mission Inn in Riverside,

California.

Tiffany had also done the Williams window for Yale’s

chapel in 1888, the Chittenden window for Yale’s library in 1890, and was the

decorator for Yale’s Bicentennial. He received an honorary Master of Arts

degree from Yale in 1903.

Charles Tiffany had died at age 90 in 1902. Louis

was vice president and art director of the company. He moved his studios to Madison

Avenue and 45th Street and purchased 580 acres at Oyster Bay on Long Island,

with an old resort hotel called Laurelton Hall. He closed the hotel to the public

and tore it down as his new mansion neared completion in 1904. The new Laurelton

Hall became the object of his creativity and virtuosity in architecture, interior design,

glasswork and painting.

The architecture was imaginative; a dream brought to life. Tiffany had no formal architectural training so he built a clay model to illustrate

his plan. The house was asymmetrical and on various elevations, and has been called

the largest and most important achievement of Art Nouveau in America. The house was

quite angular and had long horizontal rows of windows and balconies anticipating modernism

and Frank Lloyd Wright. There were 84 rooms and 25 bathrooms. Tiffany

engineered an elaborate waterscape with seven interior and exterior fountains and several

ponds and pools with exotic plants. They were connected by constantly flowing

streams of recirculated water. It opened in 1905. The final cost in 1908 was

$500,000. It was the site of lavish parties over the next ten years.

Louise Tiffany died in 1904. His oldest daughter

from his first marriage, had married and left, but his second daughter Hilda and the 17

year old twins, Julia and Louise Comfort, (known as Comfort), and 13 year old Dorothy were

still with their father. His son Charles was at Yale University and was being

groomed for a position with Tiffany and Co. Tiffany was strict with his daughters

and unkind to their suitors, but all married between 1910 and 1914, except Hilda who died

of tuberculosis in 1909.

Louis squabbled with his neighbors over electricity and

beach rights and was suspected of affairs with other men’s wives. Theodore

Roosevelt was a neighbor, and perhaps he expressed his feelings when he smashed the White

House screen!

Among his major commissions in the following years was a

mosaic drop curtain, a fire curtain, for the National Theater in Mexico City in 1909. This mammoth project required 20 workmen to fit nearly a million pieces of glass

over a period of 15 months. It reproduced the view from the presidential palace of

the Valley of Mexico, with a lake and trees and snowcapped mountains. First exhibited in

new York City in April 1911, then shipped to Mexico City, it was an accomplishment in

engineering as well as art: despite a weight of 27 tons, hydraulic pressure and

counterbalances allowed it to be raised or lowered in only seven seconds.

In 1915 a huge wall mosaic entitled Dream Garden was made

for the Curtis Publishing Co. in Philadelphia based on a Maxfield Parrish painting done in

collaboration with Tiffany. It is still there, 15 feet tall and 49 feet long. It too required nearly one million pieces of glass of many colors and degrees of

reflectivity, giving a three-dimensional effect.

The modernist Armory Show in New York in 1913 and the

great changes in perspective wrought by World War I signaled the death of both

Edwardian opulence and Art Nouveau. Tiffany turned 70 in 1918 and was being ignored

by the art world. He decided to make Laurelton Hall an art school and formed the

Louis C. Tiffany Foundation with a $1.5 million endowment. The Tiffany Studios

building at Madison Avenue and 45th Street was sold the same year, 1918.

The first young artists and craftsmen, who had to be American and aged 25 to 35 with

proven ability, arrived in 1920. They were housed in buildings separate from the

great house, but had access to it. The only formal requirement was that they should

mount an exhibition each week, when Tiffany would arrive to view their work.

Tiffany Studios began a slow decline culminating in

bankruptcy in 1932 at the height of the Great Depression. Tiffany and Company, the jewelry

business, survived.

Tiffany retreated into a private world and was seen as

eccentric. His constant companion was Sarah Hanley, a young Irish woman he met when

she came to nurse him through an illness in his 60’s. She lived and traveled with him

until his death in 1939, calling him “Padre” and always wearing yellow,

his favorite color. Under his tutelage, the nurse became a painter of some

repute. Louis built her a separate house on the estate and she lived there until her

death in 1958. Laurelton Hall itself had been sold by the foundation in 1946 and it

burned to the ground in 1957. What little was salvaged can be seen today, thanks to

the late Jeanette McKeen, in the Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Haven, Florida,

including the newly restored chapel. This museum has one of the largest collections

of Tiffany objects in the world.

Art Nouveau languished for decades. Many Tiffany

windows and mosaics were destroyed, lamps put into attics, small ornate objects

unappreciated. Only the simple Favrile glass maintained some value. In the

1970’s Art Nouveau began an upward spiral of appreciation, possibly due in part to a

reaction against the sterile, undecorated forms of modern architecture and minimalist art

showing neither pleasing form nor fine craftsmanship. Prices of fine Art Nouveau

jewelry, glass, bronzes, pottery, metalwork, and furniture have increased tenfold and more

in recent years. In July 1998 a large Tiffany exhibition was mounted by the

Metopolitan Museum of Art in New York, 130 items representing a great variety of his

work. In April 2000 the largest exhibition of Art Nouveau ever mounted opened at the

Victoria and Albert Museum in London and drew a record 250,000 persons over its four

months on view. On October 8, 2000 the exhibition expanded even more to 350 pieces,

opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and was attended by 21,000 the

first week. A reduced show goes to Tokyo in April, 2001.

It is evident that the legacy of Art Nouveau and the

legacy of Louis Comfort Tiffany are far from dead.

Appendix I

The Story of the Dream Garden Mosaic after Maxfield Parrish

The large glass mosaic mural commissioned for the Curtis Publishing Co. has a

fascinating history. In 1911 Edward Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal, had

engaged Edwin A. Abbey, Howard Pyle, and Boutet de Monvel successively to make a design

for the mural, but each had died before producing a sketch. He then organized a

competition of six leading muralists but eventually rejected all of their efforts. In his

book, The Americanization of Edward Bok, he related the resolution, quaintly

referring to himself in the third person:

"Bok was still exactly where he started, while the building was nearly complete

and no mural. He now recalled a marvelous stage-curtain of glass mosaic executed by Louis

Comfort Tiffany of New York for the Municipal Theater at Mexico City---

"He sought Mr. Tiffany, who was enthusiastic over the idea of making an example of

his mosaic glass of such dimensions which should remain in this country, and gladly

offered to cooperate. But try as he might, Bok could not secure an adequate sketch for Mr.

Tiffany to carry out. Then he recalled that one day while at Maxfield Parish’s summer

home in New Hampshire the artist had told him of a dream garden which he would like to

construct, not on canvas but in reality. Bok suggested to Parrish that he come to New

York. He asked him to put his dream garden on canvas. The artist thought he could; in fact

was greatly attracted by the idea; but he knew nothing about mosaic work and was not

particularly attracted by the idea of having his work rendered in that medium.

"Bok took Parrish to Mr. Tiffany’s studio; the two artists talked together,

the glass-worker showed the canvas-painter his work, with the result that the two became

enthusiastic to cooperate in trying the experiment. Parrish agreed to make a sketch for

Mr. Tiffany’s approval, and within six months, after a number of conferences and an

equal number of sketches, they were ready to begin work. Bok only hoped both artists would

outlive their commission!

"It was a huge picture to be done in glass mosaic (15 feet in height and 49 feet

in length). The space to be filled called for over a million pieces of glass and for a

year the services of thirty of the most skilled artisans would be required. The work had

to be done from a series of bromide photographs enlarged to a size hitherto unattempted.

But at last the decoration was completed; the finished art piece was placed on exhibition

in New York and over seven thousand persons came to see it. The leading art critics

pronounced the result to be the most amazing instance of the tone capacity of glass-work

ever achieved. It was a veritable wonderpiece, far exceeding the utmost expression of

paint on canvas."

Tiffany himself commented on the "Dream Garden" in a brochure published by

the Curtis Publishing Company. "I have been studying the effects of different glasses

to accomplish perspective, and effects of color of different textures, of opaque and

transparent, of lustrous and nonlustrous, of absorbing and reflecting glasses.

"In translating this painting so that its poetical and luminous idealism should

find its way even to the comparatively uneducated eye, the medium used is of supreme

importance, and it seemed impossible to secure the effect desired on canvas and with

paint. In glass, however, selecting the lustrous, the transparent, the opaque and the

opalescent, and each with its own texture, a result is secured which does illustrate the

mystery, and it tells the story, giving play to imagination, which is the message it seeks

to convey.

"As a matter of fact, it is practically a new art. Never before has it been

possible to give the perspective in mosaics as it is shown in this picture, and the most

remarkable and beautiful effect is secured when different lights play upon this mosaic.

"It will be found that the mountains recede, the trees and foliage stand out

distinctly, and, as the light changes, the purple shadows will creep slowly from the base

of the mountain to its top; that the canyons and the waterfalls, the thickets and the

flowers, all tell their story and interpret Mr. Parrish’s dream."

Quoted from Robert Koch; Louis C. Tiffany, Rebel in Glass

Bibliography

1. Bose, Sudip;

Preservation Magazine, March/April 1999, page 26

2. Koch, Robert;

Louis Comfort

Tiffany, Rebel in Glass, Crown Publishing, New York, 1982

3. Koch, Robert;

Louis Comfort Tiffany,

Glass-Bronzes-Lamps, Crown Publishing, New York, 1971

4. Loring, John;

Tiffany’s 150

Years, Doubleday and Co., New York, 1987

5. McKean, Hugh;

The Lost Treasures of Louis Comfort

Tiffany, Doubleday and Co., New York, 1980

6. Meister, Stanley;

Smithsonian Magazine,

Volume 31, Number 7, October, 2000, Cover and pp74-875.,

7. Paul, Tessa;

The Art of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Exeter Books, New York, 1987

8. Zapata, Janet;

The Jewelry and Enamels

of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1993

|