The Airship Hindenburg and the Seaship

Castle Rock, Two Obituaries

JOHN MORTON JONES

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library

-

BIOGRAPHY OF AUTHOR

Mort Jones, an Illinois native, has been a member of Fortnightly since the beginning of the twenty first century. He and his family moved to Redlands 38 years ago. He is a retired California Administrative Law Judge and is a member of the California and Illinois Bars. Jones completed his graduate education at the University of Michigan. In Illinois he held several governmental posts, including that of Federal Prosecuting Attorney with the Department of Justice and as a Hearing Representative for the State

Director of Labor in Trade Dispute litigation. A Navy veteran of World War II, Jones is a Past Commander and Life Member of the American Legion. He and his wife Betty have four children and 11 grandchildren.

Summary

Summary of Paper

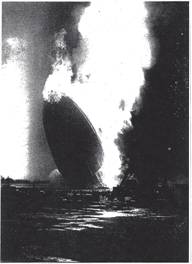

The author of this paper witnessed the fiery death of the dirigible

(or "Zeppelin") Hindenburg via radio and now relates the history

of that rigid airship and its predecessors which effectively ended

with the explosion at Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937. He then

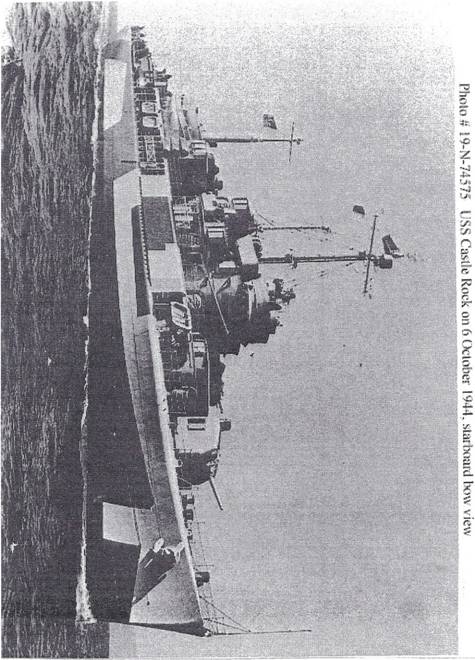

turns to the history of a naval vessel, the U.S.S. Castle Rock, on

which he served as a lowly crewman at the end of World War II

This old guy, known for most of his life as Mort, standing somewhat stooped

before you, has memories of two mechanical souls he'd like to share. One, a great

airship, the other, a ship of the sea. The airship was the giant dirigible

Hindenburg, the sea vessel was a simple tender logged by the U.S. Navy as AVP-35

but christened the USS Castle Rock.

Let's first go back to the gray days of the Great Depression. To a small town in

central Illinois. Mort's just a kid and we see him at his first job, digging out

dandelions in the yard. And he's dreaming of sailing across the sky, steering a

mighty Zeppelin. The newspapers of the day surely stirred those dreams. And the

new Hindenburg was in the headlines. It was over the Atlantic at this moment,

due to land that very evening in New Jersey. Its arrival would be radioed across

the country! So, when his chores were finished and the sun was setting, Mort

glued himself in front of the radio to absorb the event. Years later he would be

reminded of that evening when he had occasion to memorize the 19th Psalm: "The heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament

showeth His handiwork ... In them hath He set a tabernacle

for the sun, which is as a bridegroom coming out of his

chamber and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race. His

going forth is from the end of the heaven and his circuit

unto the ends of it and there is nothing hid from the heat

thereof .... " Yes, that Biblical song reminded him of the fateful day of the Hindenburg disaster

because it had come to be in two and a half millennia since the psalm was first

sung that man built a ship to race the circuit of the heavens ‘neath the tabernacle

of the sun, like a mighty bridegroom, yea, a behemoth, with skin alike silver,

coming forth from the chambers of its port, its passengers rejoicing in the luxury

So it was, at dusk, on the 6th of May in 1937, at the naval air station at Lakehurst,

New Jersey, that the zeppelin Hindenburg burst into a geyser of flame and in just

34 seconds its massive remains rained in fire to the ground. And Herbert

Morrison, there to report on national radio the dramatic and graceful arrival of

the airship from its voyage west across the ocean, broke into tears, as he

watched, aghast, in horror and spoke, "Oh my! This is terrible! Oh my! It is

burning! Bursting into flames! And is falling on the mooring mast! And all the

folks! This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world! Oh it's four or five

hundred feet in the sky! It's a terrible crash, ladies and gentlemen! Oh, the

humanity! And all the passengers!" Little Mort, aghast, shocked, terrified, saw it all in his mind's eye. As vividly

as a hundred cameras had captured the awful spectacle. For he was dreaming that it

was he at the pilot's wheel! It was he who raced to the hatch behind him to jump

out through the holocaust!

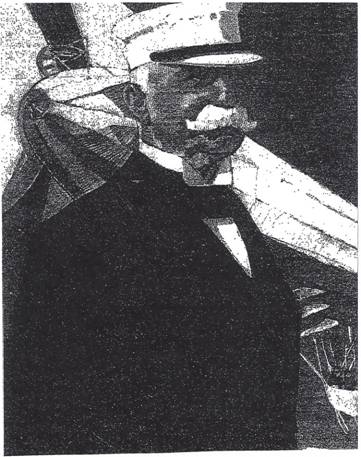

COUNT FERDINAND YON ZEPPELIN |

This image of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin has. the quality of on icon, something he had most definitely

become by the end of his life. It evokes the steely

determination that helped Zeppelin triumph against

enormous odds. Undoubtedly he owed much of his

strong sense of self 10 his idyllic childhood, spent on

the family estate of Girsberrg near Laknke Constance,

and to his close relationship with both his father and

his mother. But even as a boy •. he had to overcome

adversity. His "best of mothers" died when he was

. thirteen, and for a lime he was determined to

. become a missionary. Later, as 0 young military

officer, be fell in love with one of his cousins, and was devastated when her mother refused !hem

permission to marry. When at age thirty-one he .

finally chose a wife, he chose wisely. According to

biographer Hugo Eckener, Zeppellin's marraige to

Baroness lsaoollo van Wolff developed into a true

life-companionship and one which stood the hardest

tests the future held in store.'

In less than a minute, that great ball of flame, that crash of red hot twisted

aluminum and sturdy silvery skin ended the era of rigid airships, an era

which began before the Wright brothers were born,

Young Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin from the lakeside German town of

Konstanz on the Swiss border, even before the American Civil War, saw

that man could climb into the sky, without wings, simply by capturing

vapors lighter than the blanket of air which hugged the earth. But nature's

winds dictated the course man could travel in a balloon and only an anchor

could keep him hanging in place. How could such an object be propelled

against the wind, or, for that matter, in a calm? Oars could tame the

currents of the sea, but oars would be useless against the elements of the

sky.

These anchored balloons made excellent observation platforms, as they

were tied fast, hovering over or just behind a battlefield, but they could

not, of course, carry anyone to an assured place, nor could they lift the

weight of the cumbersome steam engines which in those days pulled the trains and turned the paddles of the riverboats. So Count Zeppelin waited until Gottlieb Daimler (the father of the great fleet of vehicles we know as

Mercedes) developed the internal combustion engine, a light compulsion

system which could be lifted easily by a sizeable balloon. And it was then

that the inventive Count took out old sketches he had made many years

before and carefully designed his dream: a massive cigar-shaped structure,

steel-ribbed, with a tail like a fish to steer in the air, with room inside for

enough bags of light gas (called "cells") to lift a whole crowd of people,

all atop an engine and propeller to counter the winds.

And this contraption, with German military backing and a good chunk of

his wealthy wife's money, was built and first flew on July 2, 1900, a

lighter-than-air craft soon dubbed a "zeppelin," a name every school kid

the world over would soon know. Thus began the evolution of the rigid

airships, marked, as one might well predict, with numerous glitches and

disasters, as fins and tails were ill-affixed, instruments measuring height

were wrongly calibrated or misread, motors sputtered and failed, and

storms overwhelmed the meager horsepower of the engines. Not to

mention the fragile internal framework of the craft. After all, the first

zeppelins flew a score of years before Henry Ford sold his first "Tin

Lizzie." By the time the first World War erupted, the Germans had a small fleet of

zeppelins (however) and their goal was not only to track the movements of

the British battle cruisers in the North Sea but to rain down bombs on

London.

The airplane, at that time, was little more than a motorized kite with very

limited range. But the German dirigibles could cruise to central England

and back. And they could carry a raft of heavy bombs. The British were, at

the same time, woefully unprepared. Their cities were targets of bright

lights, their searchlights were underpowered; their rickety planes took

forever to gain altitude and the guns they carried shot hardly more than

handfuls of peas. Their artillery was not built to bring down the high flying

monsters. But the Germans had no bombsights and were helpless in bad

weather. So the race of offense and defense was on and, in the end, the

new fighter aircraft developed by the British and manned by their daring

young men in their flying machines prevailed. The Germans dropped their

bombs willy-nilly (when the slow and defenseless dirigibles made it to

England at all). They never hit a factory or a military base and killed only

a few civilians. For all the terror the Germans sought to bring to the British

Isles, they earned only the derogation of "baby killers."

And the revered Count Zeppelin died of old age just as America entered

the War (and sealed its outcome).

Now came the disciples of the old Count with unbounded energy and

determination to build a commercial fleet of rigid airships. Foremost

among these enthusiasts was Hugo Eckener, a former journalist and

economist, an ardent admirer of Count Zeppelin and one of a number of

talented men who carried a torch for the Count's dream. Eckener had taken

on the management of Zeppelin Company. He knew the Americans wanted

a rigid airship for their navy, but had been left behind in the development

of the big airships. He knew they were building one and had bought

another from the Italians. If the Zeppelin Company could land a contract to

build such a ship for the Americans the Company would be saved, for at

that time, the Treaty of Versailles barred the Germans from building new

rigid airships. Eckener's plan worked like a charm. The Americans

finagled an excuse to lift the ban on new zeppelins and gave Eckener his

much-needed contract. So it was in 1922 that Uncle Sam acquired two new

navy airships, the one its own craftsmen built in New Jersey (from

German plans) and the new zeppelin Eckener himself piloted over from

Germany. The U.S. Army took over the Italian dirigible, named the

Roma."

The Americans had a big concern, a worry, about the use of hydrogen as

the lifting gas in the airships. They had seen a number of zeppelins explode

during the recent war when newly invented incendiary bullets from

machine guns mounted on British fighter planes punctured German

airships over England. And, after the war, an Italian dirigible had literally

disappeared over the Mediterranean as it coasted into a lightning storm.

So the Americans looked for an alternative, nonflammable gas. And in

Texas they found it. There, maybe near a ranch called Crawford, a few of

the gas wells produced a constituent called helium. That discovery came

too late for the Army's "Roma" which exploded on one of its training

flights, killing 34 of its 45 occupants

Helium wasn't quite as effective in lifting efficiency and it was very

expensive compared to hydrogen (about 70 times more costly), but it was

safe. And worth hoarding. So the U.S. locked down the supply, barring its

export to the rest of the world. And made the Zeppelin Company design

the new dirigible it was building for the navy to use helium.

In due course, Eckener's zeppelin arrived from Germany, flown over the

Atlantic with its cells filled with hydrogen. Its gas bags were then emptied

and filled with helium and she was christened the "Los Angeles." She then

went on to serve a long and successful career as a training ship until she

was retired from active service in 1932. Two other dirigibles built in the

U.S., equipped to carry scout planes in their bellies, crashed in storms.

The navy rigid built in New Jersey in the same year Eckener's zeppelin

arrived from Germany was christened "Shenandoah"( an American Indian

word meaning "daughter of the stars"). She, also, had an unlucky career,

though she was the first to fly across the continental U.S. non-stop (in

1924). The next year the Shenandoah flew into a wild midwestem storm,

broke apart in three pieces and crashed, killing 14.

England also had its troubles with these giant airships. Two were built in

1930 to be the first of many which (it was planned) would link the whole

world-wide British Empire in a network of commercial transportation

routes, served by comfortable, fast (75 miles per hour) airships. For

various technical reasons, one never passed perfunctory tests and was

never used. The other set off for India with Lord Christopher Thompson,

the Minister of Transportation, aboard with other dignitaries. The airship

bucked, at low altitude, stormy wind and rain until it unexpectantly

plopped down on the side of a hill in France and burst into flame. Most of

the 48 bodies recovered were burned beyond recognition, including Lord

Thompson. Amazingly, six crew members survived.

None of these disasters deterred Hugo Eckener of the Zeppelin Company.

He envisioned (to use his word) "voyaging" over the sea at five times the

speed of the fastest ocean liners, above the jarring waves. And he made

that dream come true. Perhaps no one else could have, for Eckener was

nearly incomparable. He was not only a diplomat, a leader, a businessman,

a dirigible pilot" a linguist and author; he was a lover of the arts; he could

recite long passages from the German classics and Shakespeare, too; he

could whistle from memory every theme from all of Beethoven's nine

symphonies.

Thus did Eckener see the great "Graf Zeppelin" completed in 1928. And

he took her around the world the next year. Thereafter, the Graf Zeppelin

established regular commercial flights from Berlin to Rio de Janeiro. The

only goal of consequence left was to establish commercial service to and

from the United States. That project would be left to the newer, faster,

more luxurious Hindenburg.

The Hindenburg was born in 1936. By that time, Hitler had risen to power

iu Germany and his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels took over the

promotion of the new giant of the skies. Goebbels saw to it that her

massive tail displayed the Nazi swastika and she was sent all over

Germany to promote, by dropped leaflets, the vote to approve the German

reannexation of the Rhineland, the first of Hitler's aggressions.

Eckener bristled at this action. In fact, Eckener was opposed to the Nazis.

He had campaigned against them in the elections preceding Hitler's

political victory in 1933. Eckener was tolerated by the Nazis only because

he had been and for a long time a highly respected public figure by the

German people. Eckener had hoped to secure helium from the United

States for his new Hindenburg, but his overtures in that regard were

quickly rebuffed because of rapidly brewing anti-Nazi sentiment on this

side of the 'Atlantic.

In the summer of 1936 the Hindenburg made several "test" runs to the

New York area (the naval station at Lakehurst, New Jersey had the

necessary facilities, including a sturdy "mooring mast" to which the great

airships were tied upon landing. Incidentally, the top tip of the Empire

State Building is a mooring mast which has never been used.

The Hindenburg was fast, with a top speed of 90 miles per hour; it was

big, nearly as long as the Titanic, and it was loaded with all the comforts

of a luxury liner. On two decks just aft and above the control gondola fifty

people could live in the style and comfort of a grand hotel. In addition to

the private cabins there were the spacious public rooms, elegantly

decorated. There was the promenade, along the giant windows slanted

downward for the views below (the airship would commonly sail along at

650 feet above the waves). Its dining tables were set with fine napery and

china and silver and bouquets of fresh flowers. Delicacies such as "Fatted

Duckling, Bavarian Style" and "Venison Cutlets Beauval" were served to

the passengers who paid $750 for a round trip (a major sum of money in

the 1930ts, more than the price of a new car). There were rare wines and a

baby grand piano in the lounge. The airship also had a comfortable reading

and writing room with complimentary typewriters and a library. And an

airtight smoking lounge.

By May 3, 1937 all was ready for the first "season" of North American

passenger service- 18 trips were scheduled. So the first official trip began,

leaving Frankfurt with only half the number of passengers-36- the airship

could accommodate. The tense political situation in Europe was probably the

cause since the year before there were waiting lists for every flight. The

return flight, nevertheless, was fully booked, largely due to many who had

planned to attend the coronation of King George VI which would occur on

the 12th.

The Atlantic crossing was smooth and uneventful except for persistent

headwinds. That meant the arrival at Lakehurst would be late by a half day

(a usual crossing would encompass perhaps 75 hours). Commander Max

Pruss decided upon a quick turnaround at Lakehurst. He knew those who

were waiting to board the flight east would be impatient, A thunderstorm

was passing along the New Jersey shore in the late afternoon of May 6th,

the scheduled day of arrival, so Commander Pruss detoured back northeast

for an hour or so, waiting for the storm to pass, Then, at 6:00 PM, in a

light rain, Pruss brought the Hindenburg slowly toward the mooring mast

and dropped the landing lines to the 231 member ground crew who would

assist the landing.

Radio reporter Herb Morrison described the scene:

"Here she comes, ladies and gentlemen, and what a sight it is,

a thrilling one, just a marvelous sight. It is coming down out of

the sky pointing toward us and towards the mooring mast. The mighty

diesel motors roar, the propellers biting into the air and throwing it back

into gale-like whirlpools ... no one wonders that this great floating palace

can travel through the air at such a speed with these powerful motors

behind it. The sun is striking the windows of the observation deck ..and

the raindrops are sparkling like glittering jewels against a background of

black velvet .... "

Crew member Lau, in the tail fin, lowered the landing wheel and then he

heard a muffled detonation- it reminded him of someone turning on the

burner of a gas stove. He looked up, but he could only see a bright

reflection against the upper panel of the gas cell above him. The next thing

he knew he was surrounded by flames. The ship shuddered.

Nearly 600 feet forward in the control car one of the officers noticed a

nearby hangar suddenly light up as if caught in a searchlight and in a split

second he heard the muffled "thud." Then another officer, leaning out a

window, cried out, "The ship's on fire!”

The tail began to fall. There was nothing else to do but wait to jump out a

window, wait until the ship was closer to the ground.

The onlookers, out there on the ground, saw a burst of flame appear just

forward of the upper tail fin. In seconds the flame engulfed the tail and

roared forward as the bow tipped up. In seconds the hull became a

chimney of fire. In moments, the bow crashed to the ground. In a blink of

an eye the onlookers at the edge of the field saw figures, some in flames,

running out of the blaze, and many, including countless numbers of the

ground landing crew broke toward the holocaust to try to help the

survivors. Commander Pruss was one, though badly burned. He lingered

near death for days. Some had severe fractures plus horrible bums. Officer

Sammt jumped, with Pruss, from the control car. Sammt closed his eyes

and ran through the flames and the crashing red hot girders and falling

wires. His uniform was afire. Frantically he rolled on the ground to douse

the flames. Only when he decided the fire was out and he stood up did he

dare to open first one eye, then the other. He could see! Then he pulled on

each ear. They were still there!

I(

~

In the end, incredibly, 62 passengers and crew lived through the horrific

event; of the 36 who died, 13 were passengers, 26 were crew members.

The first female crew member to work on a zeppelin, Stewardess Emilie

Imhof, perished on this, her second flight.

The next morning Americans awoke to screaming headlines and riveting

pictures of the Hindenburg's fiery fall. Never before had photographers

and newsreel cameramen been present to record every second of a disaster.

Soon theaters around the world were showing the amazing 34 second

sequence as the famous airship burst into flames and plunged to earth.

Hugo Eckener was lecturing in Austria during the first several days in

May,1937. Sound asleep in his hotel in Graz, he was awakened by a

telephone call from a reporter friend with the New York Times bringing

the horrible news. Eckener at first couldn't believe the caller. How could

this have happened? The Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg had made

between them more than 600 flights without mishap! They'd been struck

by lightning, survived terrible squalls and landed safely after storms. He

immediately thought of sabotage. There were many within and outside

Germany who might well take joy in the destruction of an emblem of Nazi

power.

Investigations and speculations followed but no one to this day can know

for sure just what or who caused the spark that destroyed the Hindenburg.

Commander Pruss always believed it was sabotage. The official German

investigation concluded, with near certainty, that static electricity caused

the explosion; that the stem cell of hydrogen had sprung a leak; that the

light rain at Lakehursr at the time of the zeppelin's approach had turned its

mooring lines into active electrical conductors and "grounded" the

airship- a classic case of what sailors call "St. Elmo's Fire," The tabloids

and numerous cranks and conspiracy theorists advanced their widely

varied and sometimes hairbrained ideas. But for all practical purposes, the

tragedy at Lakehurst grounded the German dirigible fleet and the outset of

World War II sealed the death of the rigid airship. The airplane became the

sole ruler of the skies.

Fast forward ,now, to the skies above the Yalu River where the first American jet

fighters are engaging the Chinese Air Force. Thirteen bloody years have passed

since the Hindenburg exploded at Lakehurst and now Korea is in flames. Where's

Mort Jones? Oh, he's been away for a time, but he's back in Danville, Illinois,

where he once cleared a yard of dandelions. Mort married his college sweetheart

and he's a greenhorn lawyer. And he's immersed in the bee hive of activities of

the local American Legion Post.

At the Post bar, Mort Jones heard plenty of War Stories from his comrades. Some, downright

hair-raising. Some had become great jokes. But Mort had none to tell. He'd never try to regale a

fellow vet with stories of his exploits as a paint chipper on a rusty tender propped up in a

backwater dry dock in California.

As the years passed, Mort's memories of countless hours of sweating work evolved to a

wondering about the fate of the sturdy vessel herself, the USS Castle Rock, which had left the

blood soaked island of Saipan at the end of the War and sailed home, surviving a killer typhoon

in the western Pacific, and with her colors proudly snapping in the wind, hailed the Golden

Gate.

But she was only a seaplane tender and no one needed her now. Even the Navy's seaplanes

were being phased out. Land-based aircraft no longer ran out of fuel over the vast expanse of

the oceans. Tactical reconnaissance would soon be accomplished with satellites. Repairs were

better made in land based facilities. Primitive shipyards were disappearing. Modern tankers

were faster, safer, and more efficient in hauling and dispensing aircraft fuel. So the seaplane

tenders were to be decommissioned. "Mothballed."

But who could know? There just might be some future use for them. They actually looked like fat

destroyers. But the preservation of these ships over the years would not be a simple process.

First, the bare steel had to be carefully coated with an anti-corrosion preservative. Zinc oxide

paint was available to resolve that problem. The camouflage coating of the hulls and

superstructure had to be chipped clear first. The turrets, the gun mounts, the winches, would

have to be shielded from the elements. Heavy plastic sheeting would provide that protection.

Internally, thousands of "fixes" had to be applied. The aviation fuel tanks had to be cleaned and

sealed. Lots of hard work lay ahead. And that was a shipyard's job to accomplish, not in months

or years, but within weeks.

Shipwrights could be found. The ships' officers had training in naval engineering. The vessel's

crewmen would be their grunts.

After a ceremony on the fantail whereby "that Jones kid" was given his "third stripe" as a

Seaman First Class (at age 19, he was giddy with pride), Jones was assigned "Keeper" of the

ship's paint locker. One of his responsibilities was to steal 5 gallon cans of paint from the Castle

Rock's sister, the USS Yackutak, which was conveniently rafted to the starboard much of the

time. That operation of replenishing the Castle Rock's paint supplies was always accomplished

in the dead of night.

Soon enough, the frustrated Captain of the Yackutak stopped speaking to Mort's skipper,

explaining to anyone who cared to listen that the skipper of "that can" on his port beam was a

"fake hot shot" too lazy to requisition paint through the proper channels.

The day finally came for Jones to be freed. He collected his mustering-out pay, handed it over

to the purported "company" which operated the rattle-trap cargo plane which would fly him

back to Illinois, retrieved from a trash barrel in the galley a beat up sheepskin flight jacket some

pilot had tossed away as too unsightly, and was driven in the "crew's jeep" to a nearby bus

stop.

Parenthetically, the crew of the Castle Rock was the only crew on all the ships tethered in San

Francisco Bay to have a jeep of its own. Each ship had a jeep for its officers. But the "gang" on

the Castle Rock, with the help of a crew mate who had been a car thief before he "joined up,"

sort of "borrowed" one of the jeeps from the Marine battalion on Saipan and hoisted it aboard

the night before their good ship lifted anchor for its journey home.

After someone relieved Jones as Keeper of the Paint Locker the Castle Rock's protective coating

was completed and, as so decommissioned, she was towed up the Sacramento River to a

massive "graveyard" and beached on the River's mud flats some forty miles or so from the

shipyard. And there she lay in limbo, but not for long.

The Coast Guard wanted her. And her sister, the Yakutak too. Their design was conceived back

in 1936 when the Coast Guard called for several new cutters, large enough for the open ocean,

short enough to allow safe entrance into small harbors, with shallow draft to permit anchoring

in uncharted or unfrequented moorings and with turning and backing characteristics necessary

for maneuvering in close quarters. And speedy, as well. In today's world the Castle Rock's twin

diesels could give a thrilling tow to dozens of water skiers all hanging on at once.

The Navy was happy to accommodate the Coast Guard. So with the world at peace and the Cold

War unforeseen by most, the Castle Rock and several of her sister ships (including the Yakutak)

were resurrected from their graveyard near Stockton, California and loaned to the Coast Guard.

Spiffied up anew, the Castle Rock was driven down the west coast to Panama and through the

great Canal into the Caribbean, around the Florida Keys and up the Atlantic coast to Portland,

Maine, her new home. Hence the rocky shore waters of New England and the cold north

Atlantic was her beat for almost twenty years. Until the Tet Offensive by the North Vietnamese

nearly overran Saigon. The Viet Cong were soon beaten back, but the battle to save the South

Vietnam government took on an urgent need for reinforcements, not only on the ground and in

the air but in the waters along the Vietnam coast as well. There was no time to lose.

Orders flew in all directions. One landed on the desk of the Coast Guard commandant in Maine.

The Castle Rock was to be immediately deployed to Vietnam, its crew included. She was to be

refitted for battle in Singapore and then drive full speed to the Mekong Delta, just south of

Saigon.

Down the East Coast she sailed, back through the Panama Canal and across the Pacific, to a

shipyard pier at Singapore. The new armament installations began, the shielded five inch gun

on the foredeck, the 40 mm cannon above the pilothouse and along the beam and aft the

superstructure. Whereupon she exploded and sank, in about 5 fathoms of salt water, right

there at the pier.

What had happened? Historians simply don't know. Navy archives record that the explosion

was due to an "engineering malfunction." Mort Jones thinks he knows. Some dockworker or

pink-cheeked seaman was sent to check the level in the high octane aviation fuel tanks in the

dusky bowels of the ship and forgot his flashlight. So he fished out a match and ...

Somehow the ship was salvaged, refloated, repaired. And arrived at the Delta in time to earn a

Combat Action Award, a Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross Citation, a Meritorious Unit

Citation, and several other honors. And then, as a gesture of solidarity, she was given to the

South Vietnam Navy and took on a native crew.

The ship was also given a new name - the Tran Binh Trong.

When the fateful, horrid day arrived in late April, 1975, at the very hour the last Americans in

Saigon climbed into a helicopter, its blades noisily flapping in neutral gear on the roof of the

American embassy, the State Department workers and their friends hurriedly escaping the

scene of the nation's first defeat, the Tran Binh Trong was bobbing on the sea just a few miles

off shore. Within hailing distance of the Trong was her sister, the old Yakutat.

The "boat people," who would soon flood out of South Vietnam into the vast ocean in open

boats on a perilous journey which might lead them to freedom in some other land, were just

planning their escape, but the crew of the Trong had a headstart and they took it, revving their

twin diesels hard and pointing their prow to a 90 degree course (straight east).

The Yakutat immediately joined the race to safety, following the Trong, her old nemesis, across

the South China Sea to their goal, Manila Bay. Whereupon the Philippine Navy assumed

ownership of both vessels and granted amnesty to their crews.

The Yakutat was set aside to be a source of spare parts for other Philippine ships, including her

sister, the venerable Castle Rock, newly christened by the Philippines as the Francisco Dogahoy.

The Dogahoy forthwith assumed her new duty which would last for 10 peaceful years,

patrolling amidst, between and among the some 7000 islands which make up the archipelago

nation, the Philippines, a country which had suffered terribly in World War II as a staunch ally of

the United States. And the crew of the Dogahoy watched as the Yakutat was dismantled, piece

by piece, part by part. Had Mort Jones paid a visit to his old ship in those days, he would be

reminded how the Yakutat had begrudgingly disgorged her paint supplies for use on the Castle

Rock 30 years before.

The Philippine Navy decommissioned their Francisco Dogahoy (born, the Castle Rock, adopted

as the Tran Binh Trong) in March, 1985. Forty one eventful years had passed almost to the very

day since the ship skidded down the way in Houghton, Washington with California champagne

from a smashed bottle dripping from its peak.

And now, in the spring, on the shore of Manila Bay, she was scrapped.

But no good War Story can end on a down note. And we certainly find none here. For the genes

of the Castle Rock live on today! Her steel hull and gray bulkheads and deck fittings and steep

ladders and rails and hatch covers in due course were forged into the great structural beams so

in demand as Manila grew into a world class metropolis. Hence the soul of the Castle Rock

resides in the city's gleaming skyscrapers of today, alive and well in her adopted land.

1'7

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archibald, Rick (with paintings by Ken Marschall), Hindenburg,

Wellfleet Press, 2005; The Madison Press ltd, 1994

Eckener, Hugo, Count Zeppelin: The Man and His Work, London:

Massie Publishing co., 1938

Toland, John, The Great Dirigibles. Their Triumphs and Disasters,

Dover Publications, 1972

Hoehling, A.A., Who Destroyed the Hindenburg, Boston: little Brown, 1962

Archives, U S. Navy, Washington, D.C., Photograph 19-N-74575, AVP-35

1$

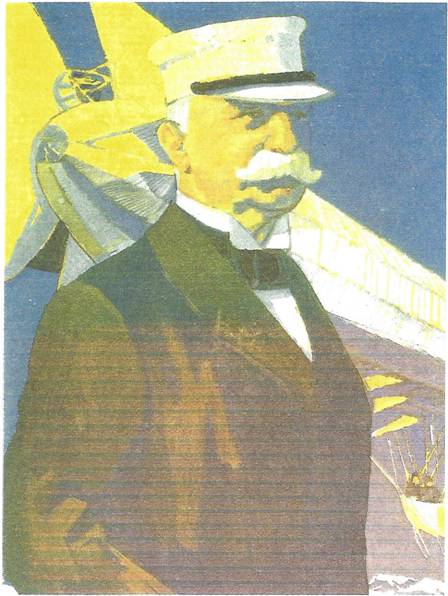

COUNT FERDINAND VON Zeppelin

This image of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin has the

quality of on icon, something he had most definitely

become by the end of his life. It evokes the steely

determination that helped Zeppelin triumph against

enormous odds. Undoubtedly he owed much of his

strong sense of self to his idyllic childhood, spent on

the family estate of Girsberg near lake Constance,

and to his close relationship with both his father and

his mother. But even as a boy, he had to overcome

adversity. His "best of mothers" died when he was

thirteen, and for a time he was determined to

become a missionary. later, as a young military

officer, he fell in love with one of his cousins, and

was devastated when her mother refused them

permission to marry. When at age thirty-one he

finally chose a wife, he chose wisely. According to

biographer Hugo Eckener, Zeppelin's marriage to

Baroness Isabella von Wolff" developed into a true

life-companionship and one which stood the hardest

tests the future held in store."

|