|

MEETING # 1561

4:00 P.M.

DECEMBER 7, 1995

The Hohokam of Central Arizona

by Northcutt Ely

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public

Library

BIOGRAPHY OF THE AUTHOR

Mr. Ely is a graduate of Stanford and Stanford Law School.

His wife is Marica McCann Ely, a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley

and Pratt Institute of Art in New York.

They have three sons, all doctors. One is a Redlands resident, Dr. Craig Northcutt.

After practicing in California and New York, he became Executive Assistant to Secretary

of the Interior, Ray Lyman Wilbur, in the Hoover Administration. He represented Secretary

Wilbur in negotiating the Hoover Dam power and water contracts.

After leaving the Interior Department, Mr. Ely practiced law in the District of

Columbia for nearly 50 years. He and his wife moved to Redlands in 1981, but he has not

retired.

His specialties are international law and natural resources law.

He has argued before the United States Supreme Court seven times. His Supreme Court

cases of most interest to a California audience were the representation of California in

Arizona v. California, and of Imperial Irrigation District in the 160 acre limitation

case.

Mr. Ely’s current cases include the representation of the City of Los Angeles and

Southern California Edison Company in the renewal of the Hoover power contracts that he

negotiated for the government 54 years ago, advice to Imperial Irrigation District in

their water conservation program, and representation of other clients in several

international matters.

He is a member of the Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, and a

trustee of the Hoover Foundation.

SUMMARY

The "Hohokam", translated as "the people who vanished", is the name

given by the modern Pima Indians to their prehistoric predecessors who built a complex

irrigation system in the Salt River Valley, Arizona. They first appeared on the scene at

about the time of Christ, and vanished soon after 1400 A.D. Some 300 miles of their main

canals, and 700 miles of distribution canals have been identified and mapped, all built

without the aid of metals or beasts of burden. Their construction evidenced a high level

of engineering skill, and mastery of principles of hydraulics. Some canals were very

large, matching Los Angeles’ Owens River Aqueduct in cross-section. Altogether, as

much as 100,000 acres may have been irrigated at various times over the centuries. The

reason for their disappearance is a mystery. It may have been occasioned by prolonged

drought, or by floods which scoured the streambed so deeply that the Indians’ brush

dams could not raise the river’s surface high enough to reach the intakes of their

canals. There is no evidence of warfare to explain their disappearance. They left no

writing or inscriptions.

THE HOHOKAM OF CENTRAL ARIZONA

Introduction

Phoenix, Arizona was named after a mythical bird that inhabited the deserts of Egypt.

When a Phoenix died, after a life of 500 years, it rose from its ashes and lived again.

The name was well chosen. Everywhere around the new town were the remnants of a

prehistoric Indian civilization that had built hundreds of miles of canals to irrigate

thousands of acres of desert lands with the waters of Salt River, as the modern Salt River

Project does. Indeed, some of the modern canals parallel the ancient ones.

The modern Pima Indians call the prehistoric Indians the Hohokam, translated as

"the people who went away", or "vanished", or "were here

before".

The Hohokam inhabited the Salt River Valley from at least the time of Christ. They

vanished from history in the early 1400’s. When the Spaniards entered Arizona, in the

sixteenth century, the Hohokam had been gone for a century and a half. When the Americans

came into the Valley in the mid-19th century, the deserted Hohokam canals had

been baking in the Arizona sun for four centuries.

The Hohokam left two intriguing questions. First, how did this stone-age people, who

lacked a written language, and had no metals or beasts of burden, manage to plan, build

and maintain these great irrigation works, and second, why did they vanish, after more

than a millennium of survival in the desert?

The Hohokam Canals

More than 300 miles of major Hohokam canals and over 700 miles of distribution canals

in the Salt River Valley have been identified.

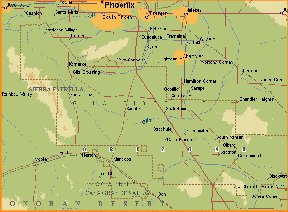

The map before you, by Dr. Omar Turney, shows the canals that could be identified on

the surface seventy years ago. Since then, many have been bulldozed, as Phoenix grew from

a small town to a metropolis of over a million people, but, on the other hand, excavations

for highways and buildings have helped the archaeologists piece together their history.

The map is not like a railroad or highway map, showing features that existed

contemporaneously. These canals were built, used, abandoned, and replaced by other canals,

also shown, over a period of many centuries.

Turney called the large group of canals diverting from the river east of the modern

city of Tempe "System One", and the group diverting west of Tempe irrigating the

Phoenix area, "System Two". Today’s discussion relates primarily to the

Phoenix area.

It seems now that approximately 50 main canals were constructed in this area between

A.D. 550 and 1450.

Approximately nine large main canals were active at any one time, closely following the

topographic contours of the valley.

The photograph before us shows three of these prehistoric canals, and the modern Grand

Canal, near their common diversion point. The mound shown in the photograph is that of

Pueblo Grande, a large village which controlled these diversions.

While the lengths of individual canals varied, the majority extended twelve to sixteen

miles from their heads. A minimum of 15 large village sites and numerous smaller

occupation areas were located within the Phoenix area. The larger villages were located at

intervals of two or three miles along the canals.

The Hohokam canals had as much as 100,000 acres in the Salt River Valley "under

ditch" at various times. This is a very large figure, equal to 40% of the total

acreage now irrigated by the Salt River Project.

The sight of thousands of acres of green irrigated fields in the midst of a desert must

have been as beautiful a thousand years ago as it is today. A Spanish priest, writing in

the seventeenth century, describing a Pima Indian corn field, said the green plants

extended in straight rows as far as a man could see.

The archaeologists divide the building of the Hohokam canals into four periods. Our

second display, of four maps, shows the Phoenix area canal system at end of each period.

These are from a highly informative essay by Jerry Howard, now Curator of The Mesa

Southwest Museum at Mesa, Arizona, written from the viewpoint of a hydraulic engineer. Mr.

Howard has been of great help to me. The first, called the Pioneer Period, covers the

centuries from the birth of Christ to 600 A.D. The second, the Colonial Period, lasted

from about 600 A.D. to 900 A.D. This is now believed to be the time of greatest expansion

of the canal systems. The third was the period from 900 to 1100, called the Sedentary

Period, when the canals underwent little rebuilding. The fourth was the Classic Period,

lasting from about 1100 A.D. to the disappearance of the Hohokam, soon after A.D. 1400.

Over the centuries, the pattern of settlement in the Phoenix area, and therefore of

canal construction, moved northward from the lowlands along the river to higher

elevations. The intensity of the movement corresponded to periods of rapid swings in the

flow of Salt River. Flood years necessitated the rebuilding of canals which had been

obliterated by floods or filled with silt. Howard has estimated that the average life of a

canal system was only 50 to 100 years.

The Indians were moving to higher ground, not only in consequence of floods, but

perhaps also because the older lands had become too contaminated by salt to permit further

cultivation. Salt River takes its name from its high mineral content, up to 1100 parts per

million, or a ton and a half of salt per acre foot of water. The Hohokam built no drainage

canals. In my boyhood, there were large areas in the valley that could not be farmed

because they were covered with alkali, as we called it. The prehistoric Indians were

blamed, rightly or wrongly.

The major Hohokam canals were large, even by modern standards. The photograph before

you shows segments of three of them, preserved in the "Park of the Four Waters",

a Phoenix City park adjacent to the prehistoric village of Pueblo Grande. The fourth

"water" is that of the modern Grand Canal. The segments preserved are located

near the diversion point where the waters of the Salt River were directed into the canals

by dams made of brush and debris. These particular canals date from about A.D. 1100-1200,

coinciding with the period of the Crusades. An engineer, W. Bruce Masse, measured these

and sixteen other canals, and calculated their capacity. Writing in Science magazine in

October, 1981, he reported that one of those shown in the photograph measured

approximately 34 feet in width at the bottom and 9 feet in depth. Three pickup trucks

could be parked in it, side by side. The distance between bank crests is about 80 feet.

These are about the dimensions of the Los Angeles Owens Valley Aqueduct near its intake in

the Sierras. For comparison, our meeting room is 30 feet wide and 10-1/2 feet high at the

top of the molding.

The canals shown in the photograph were not built to irrigate a narrow strip of

riparian lands, but were projects deliberately designed to command a large area many miles

distant from the river.

By following a northwest course into the desert, they gradually drew away from the

stream. The northernmost canal, over seventeen miles long, irrigated an area as much as

ten miles north of the river, some 60 feet higher than the riverbed.

The Hohokam as Engineers

The Hohokam engineering skill is impressive, even by modern standards. The canal

systems as they existed in the fourteenth century were not simply the systems of the sixth

or the tenth century extended to new areas, like adding a section to a hose. They were new

projects, from intake to the most distant irrigated acre. The plan of the completed canal

system had to be decided upon before ground was broken for the diversion works. The

Hohokam must have had a method, not yet discovered, of measuring the comparative

elevations of the diversion point and of the area to be irrigated before they started

digging.

The required size of the canal must be calculated. The quantity of water which must be

diverted to irrigate an acre fifteen miles from the diversion point is much greater than

the quantity that must be diverted to irrigate an acre only one mile from the intake.

Complex calculations are involved, involving the size of the future irrigated area, the

quantity of water required per unit of area, its distance from the point of diversion,

losses en route, the roughness of the canal banks, etc.

The canal had to be built on grade, to keep the water flowing, but not too steep a

grade, lest it scour the canal bottom and rupture the banks, and not too flat a grade,

lest silt and aquatic weeds choke the slow-flowing water. To keep a canal on grade for

many miles was a major accomplishment, and it had to be done without surveying instruments

of any kind that we know about.

Using modern formulas, it has been calculated that the carrying capacity of the

prehistoric canals shown in the photograph, measured at the diversion, had to be about

four times the quantity that those canals were capable of delivering to the irrigated

fields fifteen miles away. The Hohokam must have had some way, not matter how crude, of

figuring this out before they fixed on the size of the canal intake.

The intake had to be constructed at a low enough elevation above the streambed to be

served by a diversion dam. This dam, being built of brush and debris, would not be capable

of raising the river level more than a very few feet. The Hohokam had no way of building a

high or permanent diversion dam. Their fragile dams were subject to two recurring hazards:

they would be washed out by floods, and a truly severe flood would scour the river bed so

deeply that no brush dam could lift the water level to the elevation of the canal head.

At intervals, the water would be diverted from the main canal into smaller diversion

canals, and from the diversion canals into laterals, to conduct the water to the farms.

The banks of the entire system had to be above the level of the adjacent land.

The advance planning of such works required considerable knowledge of mathematics and

hydrology. But the Hohokam had no written language. If they had a system of numbers, they

left no record of it. We are left to wonder whether the calculations were made in their

heads, and whether all this know-how was passed orally from one generation to another.

Construction Methods

The Hohokam had no metals, no shovels, no wheelbarrows, no horses or burros, nothing

but their own muscles. Their tools were digging sticks and stone hoes, and baskets to

carry the excavated soil. No doubt the squaws were the ones who struggled up the sides of

the canal carrying the loaded baskets. The Arizona desert is not one of soft sand dunes.

For the most part, it is hard soil, consisting of decomposed rock knitted together by the

roots of desert plants. It is interrupted in places by layers of "hard pan", a

calcium carbonate known as "caliche".

It has been estimated that a person could excavate an average of three cubic meters

(106 cubic feet) of soil per day with a digging stick. That would be a pile of dirt about

six feet wide, six feet long, and three feet high. I don’t know who volunteered to

make the experiment; probably some professor volunteered his graduate students.

Where did the Hohokam get their digging sticks, of which thousands must have been

required each year? The cottonwood trees along the river bank would have been plentiful,

but this is a soft wood, not very useful for scratching hard soil. Palo verde, mesquite,

and ironwood trees could provide sturdier sticks, but these beautiful trees are not

plentiful in the desert, and replacements would be slow-growing. Lacking a metal knife or

hatchet, each Indian must have somehow broken off a branch—many branches—and

fashioned the ragged ends into tools. The alternative was a sharp rock, used as a hoe, but

how was it fastened to a handle? These were some of the minutiae of daily living that

successive generations of the Hohokam managed to solve every day for many centuries.

Much of this hard work was done under a broiling sun. The temperature in Phoenix is

above 100 degrees Fahrenheit an average of 90 days a year.

The Political Problem

An efficient organization must have been necessary to mobilize and command the manpower

required to build, maintain and operate the canal system.

At the beginning, it can be assumed that the men of a single village, numbering perhaps

a hundred, could be induced to go upstream several miles and start digging a canal, using

sticks or sharp hand-held rocks, to bring water to their little fields, as Prof. Haury of

the University of Arizona discovered at a village called Snaketown. This, he thought, may

have been as long ago as 300 BC, certainly not later than 50 AD.

Over the centuries, as the size and the length of the canals increased, the political

problems must have increased too. Who decided what lands were to be newly irrigated, how

much water should be transported to them, and who would benefit? How was the chief

engineer selected, the man responsible for determining the direction, the size and the

grade of the canal, and supervising construction? How many workers were needed, how was

the labor drafted, from what villages, and how were they kept on the job, away from

productive work in the fields?

Maintenance of the canals also required organized manpower.

Floods inundated the canals, filled them with silt, broke their banks, and necessitated

repairs or complete rebuilding, and in some cases caused abandonment and required

replacement by an entirely new canal. All this required the requisitioning of many, many

strong backs.

Silt deposited by the river water must have caused a maintenance problem. In modern

times, before Hoover Dam impounded the silt of the Colorado River, the Imperial Irrigation

District had to maintain a floating dredge to continuously excavate silt from its main

canal.

Canals, the world over, are subject to being choked not only by silt, but also by

aquatic vegetation. Pollen found in Hohokam canal beds shows that they were similarly

afflicted. The Hohokam not only had to dig their canals with wooden tools; they had to dig

out silt and fast-growing weeds by the same means. The modern Salt River Project fights

aquatic weeds with an unusual weapon. It dumps into its canals each year several thousand

fish of a species that eats its own weight of weeds each day. Some of those fish reach the

irrigated fields, to the delight of small boys. So far as is known, the Hohokam did not

make this discovery.

Operation must have been a political headache. Each of the large canals served several

villages, each with a population of a few hundred people. Who decided how much water

should be diverted out of the main canal into each village’s distribution canal?

Rights to the use of water in times of short supply must have been as contentious then as

they are now. On a larger scale, competition among canal systems, up and down the river,

required some kind of governmental control. The settlement at Pueblo Grande controlled the

diversion works of the canals that served most of the villages around Phoenix, but there

were diversions from the river above and below.

In times of shortage, who decided how severely each canal’s diversion should be

reduced to enable another canal to have water, and how was the curtailed flow in each

canal divided among the villages it served? Specifically, how long should each

village’s diversion from the main canal last, to be shut off in order to enable the

next village, say two miles down the canal, to receive its share, and so on for several

miles? Perhaps they hit upon the device that the Moors used during their occupation of

Spain: they threw a palm leaf into the canal, and opened each town’s headgate as the

leaf floated past it; waited a predetermined time, then threw a second leaf into the

canal, and closed each town’s headgate as the second leaf reached it.

The Hohokam must have had a workable system for administering water rights, or they

would have exterminated themselves in water wars. Perhaps they lasted over a thousand

years because they had good water lawyers. If so, it follows that the Hohokam left Arizona

because the quality of the water lawyers had deteriorated. I may suggest that solution to

the mystery the next time I visit Phoenix. Then again, I may not.

The People

The Hohokam people were world-class achievers.

What were they like? The skeletons that have been found were those of muscular men,

having the strong backs of diggers and burden carriers. The women had strong forearms, but

suffered from osteoporosis. Women were the heavy lifters then, as now. Nearly everyone had

bad teeth. It was a nation of young people. None of the dead had lived longer than 32

years.

Thirty-two seems very young to die. A thirty-year old was a senior citizen. But

Professor Weber of UCLA, lecturing on a public television program, said recently that the

average life expectancy in Europe during the dark ages was twenty-one years. The Hohokam

villages, like contemporary Europe, were populated by teenagers and young adults. But

during the dark ages when the European adolescents were killing each other off with their

metal weapons, the Hohokam youngsters were digging canals with wooden sticks, at peace

with everyone.

The Hohokam were never numerous. Their population in the Salt River Valley in earlier

centuries has been estimated as about 24,000, assuming that each of 40 known villages had

600 inhabitants. In later centuries, some estimates range as high as 60,000, about the

population of Redlands.

The larger villages had two peculiar features. One was a clay platform several feet

high. Thirty-five have been found in Salt River Valley. In later centuries these were

paved over with caliche and some were surrounded by adobe walls. One is shown in the

foreground of our photograph of Pueblo Grande.

These were not the rubble of successive villages built on top of earlier ones, like the

"Tells" in the Mideast. They were deliberately constructed, but why?

The second peculiarity was the widespread construction of what the archaeologists call

"ball-courts", somewhat larger than a modern tennis court, excavated to several

feet, and surrounded by an embankment. From their generalized resemblance to the much

larger ball-courts found in Mexico, it is thought that some kind of game was played in

them. One writer reports that 193 Hohokam ball courts have been discovered at 154 sites in

the valleys of the Gila and Salt Rivers. My uneducated guess, that they were community

baths, was summarily rejected by the experts.

The Hohokam liked plenty of room. Unlike the Pueblo Indians, they did not form

tight-knit communities, or build apartment buildings. They lived in simple huts at a

distance from their neighbors. Snaketown, south of Phoenix, had a population estimated at

five hundred to one thousand people, spread out over four hundred acres of land. Prof.

Emil Haury of the University of Arizona, who excavated Snaketown over several decades,

concluded that the Hohokam believed that "close spacing of houses was not the key to

quality living". We know something about that. His interesting article in the October

1967 issue of National Geographic on the Snaketown excavations is available for you,

thanks to Dr. James Fallows.

Their huts could not have survived summer cloudbursts, or the occasional flooding of

the Salt and Gila Rivers, and the villages were repeatedly rebuilt. What the inhabitants

did during a flood is a puzzle. They must have run to higher ground. There were no roofs

to perch on. Perhaps they huddled on top of their platforms. How did they keep their fires

alive? They could not be rekindled by rubbing rain-soaked sticks together.

This way of life changed in the Classic period, commencing about 1100. Multi-story

adobe buildings appeared. Villages were more formally planned, and some were encircled by

walls. "Great houses", like the Casa Grande south of Phoenix, were built.

These changes may have resulted from the entry into the Hohokam country of Indians from

the East, called the Salado. Their culture resembled that of the Pueblos. The beginning of

the Hohokam Classic period coincides more or less with the ending of the Chaco

civilization in Northwestern New Mexico about 1100 A.D. There is no evidence of warfare,

and the amalgamation with the newcomers appears to have been peaceful.

The Hohokam usually cremated their dead. They deliberately smashed most of their

beautiful artifacts—clay figurines, stone vessels, jars in human form, painted jugs,

etchings on sea shells, stone palettes. Some attractive examples are shown in Dr.

Fallows’ copy of the National Geographic. Whether this destruction was related to

death ceremonies is not known. The sea shells originated 200 miles away, on Gulf of

California beaches. Hohokam artists etched on them figures of humans, snakes, animals.

There is evidence that the etching was done by a method which was not discovered in Europe

until the fifteenth century. The picture was painted on the shell with an impervious

substance, clay or pitch. The shell was then immersed in a weak acid, probably the juice

of a desert plant. After a time, the portion of the surface not protected by the painting

was dissolved by the acid, leaving the picture in teas relief. My favorite design is a

horned toad, because I owned pet horned toads as a boy.

Why did the Hohokam vanish?

The Hohokam vanished from the Salt River Valley soon after A.D. 1400. The conventional

wisdom is that they were done in by drought. There is a contrary view, that their brush

and rock diversion dams were destroyed by floods that scoured the bed of Salt River so

deeply that the Indians were unable to build dams high enough to divert water into their

canals. Salt River is capable of generating huge floods. One, in 1891, was measured at

nearly 300,000 cubic feet per second, equal to three fourths of the capacity of the Hoover

Dam spillways.

Tree-rings and other sources of information indicate that although there was a severe

thirty-three year drought on the Salt River, from A.D. 1322 to A.D. 1355, this was

followed, in the year 1357 A.D., by an annual flow that had been squalled only once in the

previous four centuries. The Hohokam built no canals after that, and vanished from the

Salt River Valley a few years later.

There is no evidence that invaders killed them off. Indeed, it seems extraordinary that

the Hohokam survived for centuries without apparently having to fight anyone. Their

villages were not defensible. They had no metal weapons. There were no cliff dwellings or

mesas to which these flatlanders could retreat. But the final disappearance of the Hohokam

is not associated with any evidence of war.

When the Hohokam abandoned their canals, did they go somewhere? No new Hohokam world

has been discovered. Were they the victims of disease brought in by visitors? Did they

just finally die out from exhaustion? No one knows. Are the modern Pima and Maricopa

Indians their descendants? Perhaps, but it is hard to visualize these amiable people as

the descendants of the stone-age achievers who once peopled the valley.

If I leave you as puzzled by these questions as I am, we can take comfort in the fact

that no one else knows the answers.

1,000 Years

A final note.

The Hohokam mastered the desert for at least a thousand years. A thousand years is a

long time, by any standard.

Will we last as long as the Hohokam?

Southern California, Nevada and Central Arizona are largely dependent on importations

of water from the Colorado River, made possible by the storage of flood waters at Hoover

Dam. When that dam was being planned, it was calculated that its useful life would be

about 300 years, until Lake Mead is filled with silt. This has been extended by the

construction of Glen Canyon Dam and others upstream.

But no one, so far as I know, has stretched the life expectancy of the Lower Colorado

River Basin reservoirs to that enjoyed by the irrigation projects of the Hohokam. What

will happen then, when the muddy floods pour unchecked over the spillways of Hoover Dam?

Lake Mead will have become silt, 582 feet deep at the dam. The pumps that lift water to

Las Vegas will be out of business, and the gamblers will have to bring their own canteens.

Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu, the reservoirs behind Davis and Parker Dams, will be

swamps. The pumps that now lift water to the California coastal plain and to the land of

the Hohokam will be choked with mud. The floods will break into the Imperial Valley again,

and Salton Sea will expand to become beautiful Lake Imperial , 280 feet deep. Fish will be

swimming happily in and out of the luxury hotels, until they too fill with silt.

The odds are that our descendants, say thirty generations removed, will be the new

Hohokam, "the people who went away" from the Colorado River.

Closing on that cheerful note, I wish you a Merry Christmas.

|