|

4:00 P.M.

February 13, 2003

Gerry Bull and the Iraq Supergun

by William K. Fawcett

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library

Biography of Bill Fawcett

Born New Albany, Indiana, 1923

Graduated from New Albany High School

MBA

from Indiana

World

War II service in Europe

Korean

War service in the Pentagon

Acquired

wife Marty and three daughters along the way

Retired from Lockheed Corporation

GERRY BULL AND THE IRAQI SUPERGUN

I have chosen this topic for three reasons. The first is because it is very timely; the

UN inspectors are making their second, and perhaps final, report tomorrow to the Security

Council. The second: I hope to show the shady side of international arms deals in case

anyone is in doubt. The third reason is parochial: Lockheed Propulsion Company, and

therefore Redlands, had a significant business relationship with Gerry Bull in the 1950s

and 1960s; our guest today, Doug Melzer, was Lockheed's project engineer.

Gerald Vincent Bull was born in 1928 the ninth of ten children in North Bay, Ontario,

into a dysfunctional family. His mother died when he was three; his father was a feckless

attorney who couldn't cope with the children, his profession or the Depression. Gerry's

uncle, his mother's brother, and his wife offered to take Gerry in 1935. The wife had won

$175,000 in the Irish Sweepstakes, so they were able to care for Gerry much better than

his father or older sisters. Although the aunt was not a good substitute for his mother

because she was very domineering, she did influence him in two areas that stuck with him

the rest of his life: anti-communism and the payoff for hard work.

Uncle Phil had talked a Jesuit boarding high school in Kingston, Ontario, into accepting

Gerry even though he was two years under the admission age of 12. And he was still two

years too young at 16 for admission to the University of Toronto, but Uncle Phil again

interceded and got him admitted. This is where young Gerry acquired his life-long

fascination with aeronautics and space.

After graduation in the spring of 1948 at the age of 20 Bull took a job with an

aircraft company near Toronto but lasted only a few months. It was drudgery and dull, not

challenging to someone wanting to create. He lucked out. His mentor at the University

convinced the Canadian government to fund research in supersonic aerodynamics. He reasoned

that unless Canada were willing to let the Americans and the British, in particular, pass

Canada in the race for aerospace technology, it would lose not only the race but the

scientists as well, a drain on scientific brainpower hard for a government to contemplate.

The government made a grant of $350,000 to establish the Institute of Aerophysics at the

University of Toronto. Bull's mentor, Dr. Gordon Patterson, was put in charge of the

program to investigate supersonic aerodynamics.

Dr. Patterson selected four new engineering graduates each year to conduct the program.

They were paid $40 per week to plan and execute their research. Bull applied, but the

Defence Research Board which oversaw the grant judged him too young and immature at 20 (he

looked 16, and was still quiet and shy). But Patterson insisted that while he was an above

average although not outstanding student, Bull had shown a persistence in getting tough

jobs done. He was accepted.

Gerry embarked on his graduate program in September of 1948, assigned to investigate

the aerodynamics of supersonic wind tunnels. Supersonic flight was a mystery and a fear at

that time. Among operational vehicles, only the German V2 rocket had broken the sound

barrier. Answers had to be gotten on the ground, and the only way was to mount an aircraft

specimen in a tunnel and force very high velocity air by it. Supersonic wind tunnels were

in their infancy, and Canada didn't have one.

Bull was assigned to build one. By December Bull and his partner had completed the

math, designed the parts and ordered the hardware, much of which had to be especially

built. When they finished assembling, they discovered it was about a foot too long. No

problem. Bull cut a ten-inch hole through the wall into Dr. Patterson's adjoining office.

The tunnel worked OK, so they were on the right track, but it was too small to be of

practical use. So they designed a larger version, and sure enough when it was assembled,

it didn't fit either. Eventually Dr. Patterson's wall was removed entirely.

In the summer of 1949 Bull presented his Master's thesis and was awarded the Master of

Science degree. In August his father died, and his younger brother asked him to attend the

funeral. He hadn't seen his father in years, nor any other of the Bull family. This turned

into a terrible row which brought out all the ill feelings between the Bulls and Gerry's

adopted family on his mother's side. Gerry was so hurt that he never again saw or talked

to his brothers and sisters.

Bull started work on his PhD at the Institute of Aerophysics about the time the Defense

Research Board awarded the Institute a $200,000 contract to design, build and test a

supersonic wind tunnel capable of Mach 7. Bull was assigned to design the test section,

where the highest air velocity is produced. The purpose of the wind tunnel was not

disclosed, but it was apparent that the testing of a weapon system was involved. It turned

out that Canada was working on an air-to-air missile, code named Velvet Glove, to shoot

down Soviet bombers if they attacked Canada. The Cold War was heating up.

The missile development work was being done at CARDE, the Canadian Armament and

Research Development Establishment, located about 30 miles north of Quebec City. The

Velvet Glove project needed an aerodynamicist to design the missile body, the wings and

the fins. Gerry Bull was selected. He spent weeks at CARDE. In the meantime he was still a

student working on his thesis. He completed it in March of 1951 and transferred to the

CARDE staff on April 1st. He received his PhD in May, the youngest ever at the University.

The price of such frantic activity was the severe loss of weight and a near-nervous

breakdown.

At CARDE Bull was no longer in an academic environment where the goal was knowledge;

for the first time he was in an organization dedicated to producing war materiel. Velvet

Glove was an air-to-air missile 6 feet long, 8 inches in diameter, weighing about 350

pounds, and guided by radar. Bull directed a small technical staff that worked the

details, leaving him to work on the bigger problems and ideas. He would never become a

detail man.

The question of confirming Velvet Glove's aerodynamic characteristics by testing

appeared to be insurmountable. The normal method, wind tunnel testing, was out of the

question because CARDE had no wind tunnel, and the one being finished in Toronto was too

small. Bull came up with the solution: it was the idea that would become the central theme

of his life. For years CARDE had conducted tests of artillery shells by firing shells

through a 350-foot long vacuum chamber while instruments and cameras were recording their

flights. This allowed a determination of how the shock waves created by supersonic speeds

affected the stability of the shells.

Bull reasoned that the vacuum chamber would allow the wind tunnel procedure to be

reversed. Instead of a stationary test specimen and high speed airflow, the model would be

tested by being fired from a gun at supersonic speed through the static atmosphere. Bull

built a scale model of Velvet Glove and tested it. The tests were successful, and provided

the Velvet Glove project team the data essential to proceed with a full-scale launch.

Bull and his team were very unpopular with other sections of CARDE. He had been

promoted several times, much more quickly than normal, and aroused jealousy. He had

occasionally embarrassed his superiors by end-running them and by grandstanding with the

press. The final straw came when he was the subject of a cover story in Maclean's, a major

monthly Canadian magazine. His boss talked him into an interview. When the magazine came

out in March 1953, Gerry's portrait was on the cover under the heading"Gerry Bull:

Boy Rocket Scientist". It cinched his reputation within the Canadian civil service as

a self-serving publicity seeker.

Up to this point in August 1953 Bull had never even had a date. He was too busy. He was

talked into double-dating, and fell madly in love with his date. She was the daughter of a

wealthy French-Canadian doctor living across the river from Quebec City. She was a beauty,

cultured, Catholic and a talented painter. Dr. Gilbert wanted her to marry a

French-Canadien, but it didn't work. They were married in July 1954. Eventually the doctor

and Gerry became very close.

Velvet Glove had grown to the point where 600 technical personnel were working on it.

300 missiles had been made and fired at a new site in Alberta. Then suddenly in mid-1954

it was canceled. After Sputnik, the Soviet threat was no longer bombers; it was the

intercontinental ballistic missile, against which the air-to-air Velvet Glove missile was

useless.

Bull's reputation for aerodynamic accomplishments continued to grow. He attracted

international attention by attending technical conferences and presenting papers. He

became a good friend of Dr. Charles Murphy, later head of the Ballistics Research

Laboratory of the U. S. Army Ordnance Corps' Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. The

Laboratory was the U.S. counterpoint to the Canadian CARDE. As the relationship between

the two men grew, it resulted in U.S. contracts to CARDE to support Bull's work. This was

the opening of a whole new chapter in Bull's life.

After the cancellation of Velvet Glove, Bull turned his attention to investigating an

anti-ICBM vehicle. He reasoned that an ultra-high velocity gun firing shrapnel at the

signature created by the shock wave of an incoming warhead as it re-entered the atmosphere

would destroy the warhead. He was already achieving ultra-high velocities of 20,000 feet

per second from guns.

In April 1958 Bull made a horrendous blunder that would further alienate him from his

CARDE superiors and the Canadian government. He told the Montreal Star that he was working

on a gun-launched satellite that would be part of the Canadian program to develop an

anti-ICBM missile. He also said that the U.S. would provide him a Redstone rocket for

launching a 15-foot long missile that would achieve orbital velocity when fired at

altitude. He not only spilled the beans on his pet project, which was not approved, but he

gave away some CARDE secret information and exposed his relationship with the U.S., which

was also not known. The head of CARDE and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker were furious.

For the next three years he would operate in an increasingly abrasive environment at

CARDE, but his relationship with Dr. Murphy and the U.S. military would become closer and

closer. Finally, in February 1961 Bull resigned from CARDE.

Bull had caught the eye of the dean of engineering of McGill University in Montreal.

The dean was a well-respected researcher in gas dynamics who believed in Bull's work. One

month after he left CARDE, Bull was appointed a full professor of engineering science in

the Department of Mechanical Engineering. At 34 he was the youngest ever appointed. He was

assigned to work on the aerodynamics of aircraft and space vehicles at extreme speeds and

altitudes. He also continued his consulting work with U.S. military and corporations.

This was the time when testing of intercontinental ballistic missiles was beginning in

the West. It was discovered early that re-entry into earth's atmosphere at near 20,000

miles per hour resulted in such friction that enormous heat was generated, enough to

destroy the re-entry body. This was among the most serious problems to be overcome. Bull's

high velocity gun tests at CARDE provided data that could be extrapolated to address the

re-entry heat problem.

Bull and his boss worked on a plan for firing a gun to pursue the nose cone study and

ultimately to launch a satellite. He needed a remote spot where firing the guns would not

disturb anyone.

Bull found the spot he was looking for: a remote thousand-acre hilly and wooded site at

Highwater, Quebec, 60 miles south of Montreal on the U.S. border with Vermont. His

father-in-law bought the property, which McGill rented for $180,000 a year, a hefty price.

Dr. Gilbert and Bull each built homes at the site, which also had a swimming pool and

tennis courts.

McGill code-named the project HARP, for High Altitude Research Program. Their immediate

goal was to fire instrumented shells into the stratosphere to gather weather and

meteorlogical data. Their ultimate goal was to launch shells containing solid rockets,

which would then be ignited at altitude to achieve orbital velocity of 17,000 miles per

hour. This is the definition of a satellite.

Experimental work and sub-scale testing could be done at Highwater, but HARP required

an ocean range away from populated areas, so McGill selected Barbados, where it was

conducting other programs.

Funding was the problem. McGill provided a little, but the main hope was the Canadian

government. This is where Bull's rocky relations with CARDE and Ottawa came back to haunt

them. The results of requests for funding resulted in at best long delays in approval and

at worst flat disapproval. Bull turned to his friend Dr. Murphy at Aberdeen for help. The

U.S. Army was wrestling with the Air Force over jurisdiction in space, and was about to

lose. Murphy and his bosses saw the HARP project as a way to keep the Army's foot in the

door. The Army issued a $2000 contract to McGill, a ridiculously low amount to avoid

drawing attention. The covert part of the contract was for the U.S. to supply hardware to

make Barbados operational.

Murphy quickly fulfilled his commitment. He found two 16-inch spare, unused battleship

gun barrels, about 60 feet long and weighing 125 metric tons; he also provided a 4-in gun

barrel for preliminary experiments, a $750,000 radar tracking system, a giant traveling

crane and a truck. Bull had the rifling grooves removed from the gun barrels so the

projectiles would not spin. Murphy arranged for an Army landing craft to deliver the

equipment to the Barbados beach, where it was moved over temporary rail tracks 3 miles to

the launch site. McGill engineers had built the concrete gun emplacement, so everything

was ready to go. Barbados was a well-equipped, well-instrumented launch site.

A 16-inch naval gun was also installed at Highwater. It was fired about 450 yards into

a tunnel in a hillside to experiment with propulsion charges and methods of increasing

muzzle velocity; the performance of sabots was also evaluated.

Starting in the mid-1950s Lockheed Propulsion Company's predecessor company, the Grand

Central Aircraft Company's Rocket Division, conducted extensive tests of gun-boosted

rocket motors. One of the ideas for achieving the ultra-high performance required of a

satellite was advanced by Wilbur Hartzell, whom some of you may remember, and Doug Melzer.

This was to seal the nose and aft ends of a thin-walled rocket motor and fill the annulus

with a liquid whose specific gravity approximated that of the rocket motor to prevent the

case from collapsing. The tests in 1963, done under the cognizance of the Ballistic

Research Laboratory at Aberdeen, Maryland were successful in demonstrating that solid

propellant could withstand the high acceleration of a gun without igniting or detonating.

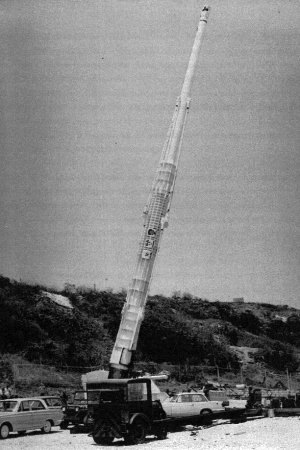

16-inch Gun at Barbados >>

Dr. Bull learned of the Lockheed successes and as part of the overall HARP program,

awarded a $50,000 contract to continue the program, the objective of which was to place

payloads, especially communications satellites, in earth orbit. Doug Melzer was the

Lockheed project engineer who oversaw the delivery and testing of many rocket motors at

both Highwater and Barbados during numerous visits to those sites. He became well

acquainted with Dr. Bull as a result.

HARP continued to be funded off-and-on by the Canadian government, always late, in

spite of the prevailing ill will towards Bull. The U.S. continued its funding, which only

increased the skepticism in Ottawa, which began to think of HARP as a U.S. program. A

high-level Canadian report neatly summed up the advantages and disadvantages of a

gun-launched system: guns could launch payloads to great heights more efficiently than

rockets; it was cheaper than rockets, and more accurate; the disadvantages were that the

diameter was restricted to the bore of the gun, and the payload and its contents had to be

able to withstand extremely high acceleration forces, up to 10,000 times the force of

gravity.

In the meantime the U.S. Army had hedged its bet by opening a 16-inch HARP range at its

Yuma Proving Grounds. In November 1966 it fired one of Bull's missiles to a height of 112

miles, a record that stood for over 25 years. But in June of 1967 the Army closed the Yuma

program because of the increasing costs of the Vietnam war. Just before that, however, the

Army transferred $3.5 million worth of equipment to enhance the ballistics capability of

Highwater. Coupled with the Canadian refusal to continue funding, the U.S. decision meant

the end of HARP. In its brief life it had provided a wealth of meteorological data, so it

had provided some benefit. Bull resigned from Space Research Institute, the name which had

been given to the McGill project.

A year later an unexpected thing happened: at a meeting in Montreal between McGill and

representatives of the Canadian and American governments to decide how to dispose of the

HARP assets, Bull served notice on McGill that it would have to meet all provisions of the

Highwater lease, which was expiring in a few weeks. One provision required that Highwater

be restored to its original condition within thirty days, an impossibility considering the

tremendous changes which had been made through building and deforestation. Over the years

Highwater had become a very well equipped laboratory for ballistic design and evaluation.

Bull offered to waive the clause if McGill, with concurrence from Canada and the U.S.,

transferred all HARP facilities and equipment at Highwater and Barbados to the Space

Research Institute, which he had incorporated in the meantime. He held the trump card.

McGill was anxious to get out, so it agreed.

Bull then approached the Bronfman brothers of Montreal and Seagrams fame who then

bought the business, which they operated for about a year. It was renamed Space Research

Corporation, and Bull was appointed the Technical Director. NASA and then the U.S. Army

offered contracts, but were restricted to contracting classified work within the U.S..

Problem solved: with Bronfman money Bull bought land in Vermont on the other side of the

border from Highwater. That satisfied the security requirement. Then the International

Boundary Commission granted permission to build a private road across the border to

connect both sides of the company.

The Bronfmans changed their plans and sold at great profit the subsidiary to which they

had attached Space Research Corporation. Bull's shares enabled him to pay off the

Bronfmans' investment. The Bronfmans introduced Bull to one of their bankers, First

Pennsylvania Bank of Philadelphia, which was to be entangled with Bull's finances for

years.

Bull's work with artillery at CARDE and HARP had gained him an international reputation

in ballistics and artillery design. Military establishments around the globe were aware of

the 16-inch gun tests and the altitude records they had produced. So it was no surprise

that visitors came to Highwater to consult with Bull. Kirtland Air Force Base in

Albuquerque needed help with a missile nose cone design. It was 3 feet long and weighed

100 pounds. Bull welded two extra tubes to the 16-inch gun at Highwater, making it over

150 feet long. The nose cone left the barrel at 10,000 feet per second as it traveled a

mile before hitting a hillside. Films of the flight showed that the nose cone performed as

expected.

The U.S. Army issued a small contract to continue the studies of guns as ABM

possibilities. To do so, it had to divulge highly classified information, which Bull was

not cleared to receive. That was solved when Senator Barry Goldwater sponsored a private

Act of Congress to grant citizenship to Bull. It passed, so now he controlled development

facilities in Canada and Vermont connected to each other, and he was a citizen of both

countries. How neat!

The main thrust of Bull's effort and international contacts was centered around 155 mm

artillery pieces, which were owned by armies around the world. There were 155 mm guns,

with a range of about 12 miles, and 155 mm howitzers, with shorter range. The guns were of

primary interest, and there were so many everywhere that it was not practical to consider

modifying them. Improvements had to come from the projectiles they fired. It took Bull and

his crew four years to develop a projectile that would reach almost 20 miles and deliver

highly fragmented shrapnel.

This took Bull past the fork in the career road between peaceful altitude and satellite

exploration on one fork and military work on the other.

In 1973 a large Belgian munitions company, PRB, paid $75,000 for firing demonstrations

of the new shell in West Germany. The PRB general director convinced Bull that he needed

an international partner if his technology was ever to escape the laboratory. Government

arsenals and the military-industrial complex, particularly in the United States, to which

most nations looked for technical leadership, dominated the field. As a result, Space

Research Corporation, International was formed in Brussels, with PRB investing and owning

38% of the shares. Bull was also talked into designing a new 155 mm gun with a longer

barrel and greater range and accuracy.

SRC-I began to promote the new gun and projectiles. Interested delegations started

pouring in to Highwater for briefings and demonstrations. Most came via the crossroads

town of North Troy, Vermont. Two roads led into the compound. One approached a chain link

gate and fence, which was controlled by an armed guard. Nearby was a U.S. Customs

inspector who checked all incoming and outgoing vehicles. The road continued past

administration buildings and shops into Canada. The second road crossed the border at an

unattended and unmarked crossing. The International Boundary Commission had given

permission for this road--the first new crossing allowed in 50 years anywhere along the

4000 mile border. This road went through the area on the Canadian side where many of the

guns were installed and where the main industrial complex, including an auditorium for

lectures, was located. To the north were a manned gatehouse and a Canadian Customs

station. The one rule which governed: visitors and Americans entered through the south

gate, and Canadians through the north gate.

Visitor traffic reached the point where North Troy, Vermont, became a small center for

services, including a 30-room lodge and restaurant where in the evening the visitors and

now their imported Montreal ladies were entertained in lavish parties. This is where Bull

made his theatrical appearance to welcome them.

From the mid-70s the company exploited its unique location. "Because it straddled

the border, it could mix and meld the export laws of the two countries to its benefit. For

example, the U.S. allowed the export of arms to allies such as Israel. Canada, on the

other hand, banned all arms sales into the Middle East. So the development work on an

Israeli extended range shell was done on the Canadian side, but Bull had the shells built

in the U.S., and Washington issued an export permit for them to be sold to Israel. At the

same time, although Ottawa had stringent laws governing the export of arms, it did not

require certificates of end use for 'inert' items sent to friendly nations. That meant

Bull could export artillery shell cases to anywhere in Europe, just so long as they were

empty. In that way he could send them to PRB in Belgium., which in turn would load the

shells and sell them anywhere that Belgian law would allow. And Belgian law was a lot less

stringent than Canadian or U.S. law."

In late 1975 Portugal granted independence to Angola, the southwest African country.

Local political groups were unable to settle their internal disputes, and called on

outsiders to help them gain control. Three nations each supported a different faction: the

CIA, which sought to prevent Communist take-over, Russia and South Africa. The CIA quickly

bowed out, leaving Russia (with Cuban help) and South Africa battling to gain control.

Russian rockets were outdistancing South Africa's 155mm guns. South Africa had been unable

to update its weaponry because the United Nations had previously sanctioned it with an

arms embargo to counter apartheid.

Six months earlier an international arms dealer representing Israel had ordered 15,000

extended range 155mm shells from Bull. Bull had been granted a U.S. export permit to ship

the empty shell casings to Belgium, where they were to be loaded with explosives and fuses

for shipment to Israel. Israel had been working closely with South Africa, had ordered the

shells on behalf of South Africa, and ultimately transshipped the shells to South Africa.

The increased range was an immediate hit with the South Africans, who quickly ordered

53,000 more. The contract was between a Bull-owned Barbados subsidiary and a Liechtenstein

front.

Bull wanted to make certain that he was on solid ground, so he went to the U.S. Office

of Munitions Control for oral approval of exporting empty shell casings. He received the

approval, and he followed up with a letter asking for approval in writing, which he got.

Around that time an election in Barbados had resulted in the defeat of the

administration sympathetic to Bull and the seating of one opposed to his activities in

their country. Following the election the pressure on Bull became so great that he moved

the operation to Antigua.

Now shell cases were being exported to Belgium and Antigua; a visit to Spain added that

country to the list. Bull had a crew in South Africa teaching the Afrikaners to load and

test-fire the extended range shells.

And now, surprise! Fidel Castro got into the act. He told a visiting Rhodesian

guerrilla leader that his intelligence had picked up reports of what was going on in

Barbados and Antigua. The visitor was on his way to make a speech in Canada, and he called

a press conference to relate what Castro had told him. Bull's Space Research Corp. was

implicated, and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was infuriated. He ordered the RCMP to

investigate. British intelligence became involved. So did two young investigative

journalists, who spent the next two years unraveling the trail. The BBC and CBC networks

prepared and aired documentaries alleging that all the shipments ended up in South Africa.

The U.S. government got interested, and convened a grand jury in Philadelphia to

investigate. Eventually, in spite of his letter of approval from the Office of Munitions

Control, under threat of imprisonment to many of his employees, Bull agreed to a plea

bargain to save them from trial. He was sentenced to six months in jail at the

minimum-security federal prison at Allenwood Prison Camp in Pennsylvania. While he felt he

had done nothing illegal, he clearly had violated the intent of export restrictions. Bull

was na´ve and on the innocent side, but he was not so na´ve or innocent that he didn't

know how his empty artillery shells would be used---or that shipments ending in South

Africa were illegal, regardless of how circuitous the delivery route.

In the four months between sentencing and commitment to Allenwood, Bull began to drink

heavily. That and the failure of his businesses caused him to have a nervous breakdown,

which resulted in confinement to a psychiatric hospital, where the doctors were concerned

that he might commit suicide. He pulled out of his depression during his jail term, and

emerged in February 1981 charged up ready to resume his career. He would never forgive the

United States or Canada for their treatment..

Prior to his trial Bull had been introduced to an agent for the Chinese government, and

he now pursued that relationship. He was invited to visit Bejing and Chinese weapons

factories. He was requested to submit a proposal to upgrade Chinese artillery

capabilities. The result was a series of contracts over several years which totaled about

$25 million dollars, but which profited Bull very little. The Chinese haggled so during

negotiations that they ended up getting twice the work for one third the price from the

na´ve Bull. It was so bad that the Chinese eventually gave back some of the concessions

they had won from Bull for fear he would give up.

Artillery shells have always experienced base drag, which reduces the velocity and

therefore the range. The drag results from the vacuum which is produced behind the shell

as it travels through the atmosphere. Part of Bull's program to increase the range of

Chinese artillery was the introduction of a very small motor fitted into the base of the

shell which released gas into the vacuum when it was ignited, and reduced base drag. Bull

at his finest!

Even though it was not profitable, the cash flow from the Chinese contracts enabled

Bull to re-establish his company in Brussels. As the contracts phased out, he sought a

contract from Egypt without success, but he did receive small orders from Yugoslavia and

Spain. They were not sufficient to sustain the company, however, so hope appeared when a

call came in late 1987 from a representative of Iraq in Germany. Iraq had been at war with

Iran since 1980, and Bull was determined not to get involved with that, but the

representative assured him that they were looking for long-term help.

The Iraqi-Iranian war had settled down into infantry and artillery duels because

neither had an effective air force. Neither country was looked upon with favor, at least

by the Western nations. They were considered pariahs, each getting what it deserved. The

U.S. generally tilted a little in Iraq's favor because the Ayatollah Khomeini had deposed

the favored Shah of Iran, and Saddam Hussein's repression of Iraqi dissidents had not yet

become widely known. Western nations had banned the sale of armaments to both sides, but

the U.S., Russia, France, China and Brazil ignored the embargo and sold weapons to Jordan

and Kuwait for delivery to the adversaries. The U.S. sold weapons in what would become

known as the Irangate scandal. South Africa and Austria sold both sides artillery based on

Bull's designs, from which he derived no income. By the mid-1980s Iran had about 350 155mm

guns and Iraq 400. Bull had no hand in this.

In early 1988 Dr. Bull and his two sons flew to Baghdad as guests of the Iraqi

government. Saddam Hussein's son-in-law, who was in charge of rebuilding the nation, was

their host. They toured military bases and factories. Bull was asked about developing

bigger artillery, and he agreed to do so. The Iraqis also wanted his help in their space

program, which consisted of clustering five Soviet Scud missiles as a first stage, and

buying second and third stages. This certainly interested Bull not only from the technical

standpoint but also because he felt he could convince the Chinese to sell rockets for the

second and third stages. And, oh by the way, if it was a satellite they wanted, how about

a gun-launch based on his HARP work in Canada. The Iraqis were not na´ve. They knew, as

well as everyone else, that a gun capable of launching a satellite was also capable of

launching an intercontinental missile. They were very interested in the supergun idea, and

asked Bull to prepare a proposal. They were so eager to get started that they authorized

contract work to begin while the proposal was being prepared. They settled on $25 million,

but insisted that the project had to be completed in five years, a virtual impossibility.

It was code named Babylon. There would be a one-third scale model for sub-scale testing;

this was Baby Babylon.

The specification developed by Bull and his team called for a barrel whose bore was 1

meter, or 39 inches. A telephone booth would just about fit inside. It would be 515 feet

long--almost the height of the Washington Monument. The barrel alone would weigh over 1650

tons; each of four recoil cylinders weighed 60 tons; and the breech weighed 182 tons.

Total weight was a staggering 2100 tons. It would stand 350 Feet tall. The recoil would be

in a 100 foot deep pit.

The barrel was to be made in twenty-six flanged sections that would be bolted together.

It would be twelve inches thick at the breech and tapered to about three inches at the

muzzle. It was designed to withstand a staggering pressure of 70,000 psi.

Iraq's worldwide undercover procurement network was put to work buying the necessary

parts. They were to be delivered to Jordan or Kuwait or another friendly Arab country for

transshipment to Iraq. They were ordered under the guise of ultimate use by the petroleum

industry. Some disruptions occurred when intelligence agencies of various countries picked

up the trail of strange purchases and caused them to be canceled. A few jail sentences

resulted.

The most important part of the procurement was the gun barrel. It was also the most

difficult to conceal. Its size, its tapering thickness and its exacting specifications

were not plausible for a petroleum pipeline. Two sets were ordered from the British

company Sheffield Forgemasters. Sheffield was so suspicious of the end use that it sought,

and received, export approval from the British Government as part of a petroleum pipeline.

Dr. Bull became intimately acquainted with Iraq's weapons programs and their status,

and this would lead to his undoing. He was taken on tours of their secret facilities. He

was working not only on Project Babylon but also on artillery and missiles. He adapted

some of the Baby Babylon test firings to test nose cone materials, in this most difficult

technical area. He and his sons attempted to buy a bankrupt Northern Ireland carbon fiber

fabricator, Lear Fan Company. Had this been successful, two objectives would have been

met: a supplier of carbon fiber for nose cones, which was an embargoed material; and it

would have been a step toward diversification for the Bull enterprise, which the sons

promoted to get out of the arms business. The British Government saw through the

subterfuge and refused to allow the sale.

In December 1989 Iraq launched its three stage rocket for the first time, which

surprised the West that they were that far along. It was highly publicized. The first

stage, the bundle of 5 Scud missiles, performed OK, but the second and third stages didn't

separate. Bull had not been able to convince his Chinese friends to sell Iraq an upper

stage for the rocket.

For some time Dr. Bull was fairly certain that his phones were being tapped and his

mail opened. He knew that the CIA, the British M16 and the Israeli Mossad agencies were

aware of his activities. He had even briefed the Israelis. But the plot began to thicken.

His Brussels apartment was entered several times. While his office had always been a mess,

he was meticulous at home, so the entries were obvious. On one occasion a set of his

drinking glasses was replaced by another, unfamiliar set. It was clear that someone was

sending a signal, and it was meant to be frightening.

In late summer Sheffield Forgemasters began delivery of the Babylon gun tubes. There

was much apprehension that they would be stopped enroute, but that didn't materialize.

Project Babylon was really underway. The site north of Baghdad was ready. Massive

excavations had been made in a mountainside to accommodate the gigantic structure required

to support the gun and absorb the recoil of 30,000 tons. Recoil speed would be about 8

miles per hour, but the recoil was designed to be stopped within about 8 feet. Imagine

that! Ten tons of propellant would be ignited to propel the projectile through the 515

foot barrel.

Project Babylon was a military monstrosity. It could not be targeted because neither

its azimuth nor its elevation could be adjusted, the primary requirement for an artillery

piece. It could not be re-loaded within hours or maybe days. Because of its size and

weight it could not be hidden. Therefore it would be a sitting duck in the event of a

conflict. For this reason Iraq's neighbors, especially Israel, had written it off as a

potential threat. What concerned Israel and the intelligence agencies of other nations was

the Iraqi missile project. Bull had earlier sensed, and later became convinced, that that

was the real reason the Iraqis had been interested in him. They merely tolerated Project

Babylon.

After the Iraq missile launch the pressure on Bull to stop working with the Iraqis

increased. Israel requested a meeting with him in Brussels. Three men met with him for two

hours. Presumably they told him they knew what he was doing, and told him to stop. Other

rumors in the netherworld of arms dealers linked Israel hiring a Palestinian hit-man.

Whatever the situation, it was clear that Bull had better withdraw for his own safety.

He didn't, and on March 22nd 1990 he was assassinated as he got out of the elevator on the

sixth floor of his Brussels apartment.

The Brussels police investigated the murder, but were unable to determine the

responsible party. There were many suspect intelligence agencies, with the Israeli Mossad

the most likely because Israel appeared to be the most likely target of Iraq's weaponry.

Dr. Bull had started as a starry-eyed technical expert with no business instincts, had

crossed over into the murky area of international armament to keep his business afloat,

and had paid the ultimate price for his involvement.

EPILOG

This paper is being presented as a tense situation exists between the United States and

the United Nations, on one hand, and Iraq on the other. Because this paper is about Dr.

Gerald Bull and Iraq, it is timely to speculate about what might have happened if Bull had

not been murdered, which occurred three years after the end of the Iraq-Iran war and six

months before Iraq invaded Kuwait.

Bull did not work for Iraq until after the end of its war with Iran, but he was very

active thereafter until his death. The acceleration of the design, procurement and

production activities of Iraqi armament under Bull's direction inevitably led to the

conclusion that Iraq was intently arming itself even though sanctioned by the UN. Bull

quickly made significant improvements to the range and accuracy of its artillery, although

it is this writer's opinion that this did not significantly affect the Gulf War because

the Iraqi army so quickly vacated the southern part of its country where it might have

been effective.

But Bull's leadership in the development of Iraq's missile capability was unmistakeable

and was the most troubling to potential target nations, and surely led to his death.

Although Bull did not participate in the development of the content of warheads, and so

had nothing to do with the chemical, biological and nuclear materials which cause the

current tension, he did make it possible to deliver them to potential targets. This is

where Bull's expertise was of such value to Iraq. Without Bull those warheads would be

useless.

He showed how five Scud missiles would perform aerodyamically when bundled to create

the first stage of a three-stage intercontinental ballistic missile. The world was

surprised that Iraq was that far along when the first launch occurred. It must be pointed

out that Bull probably had nothing to do with the 39 Scud missiles that were later

launched against Israel during the Gulf War.

More importantly than that, though, was the development and procurement work he did

utilizing his prior experience on missile nose cones. This was probably the area where

Iraq would have lagged the most without Bull's leadership. We have already shown that

surviving the tremendous heat build-up is probably the most difficult problem of reentry

vehicles. The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster ten days ago drove home that point so

tragically.

In spite of the UN sanctions, sales of Iraqi oil have given the country the financial

ability to sustain its political ambitions. So I believe that one can conclude that had

Bull lived, Iraq's ability to deliver missile warheads capable of mass destruction would

have been even more ominous and the tense political situation we face today would have

been upon us much sooner.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Lother, William: Arms and the Man Ivy Books, New York

Adams, James: Bull's Eye Times Books

Discovery Channel: Super Cannon 1/14/98 9 PM

|