|

MEETING #1583

4:00 P.M.

FEBRUARY 27, 1997

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church

by The Rev. Douglas G. Eadie Ph.D.

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley

Public Library

SUMMARY

The ancient Ethiopian Orthodox Church was founded in the 5th century and for most of

its history has been isolated from the mainstream of Christian history and growth in

Europe. This was due to two factors. One is that its theology was rejected by both the

Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches at the Council of Chalcedon in A.D. 451.

The second is its political and geographical separation from Europe by the Muslim

conquests in North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The result has been that it has developed unique practices and rituals and possesses a

Biblical canon that differs from both Catholic and Protestant churches. This paper

summarizes some of these features.

THE ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church belongs to a group known collectively as the Oriental

Orthodox Churches. Other churches in this grouping are the Egyptian Coptic Church, the

Syrian Jacobite Church, the Mar Thoma Church of India, and the Armenian Orthodox Church.

These churches are similar in many respects to the Greek or other Orthodox Churches, but

differ in that the Oriental group does not accept the dogmas of the Fourth Ecumenical

Council, that of Chalcedon in A.D. 451. In fact, the doctrine of these churches was

condemned at that Council, and they were declared heretics. On the other hand, both the

Greek Orthodox and the Roman Catholic Churches accept the decrees of Chalcedon. Sometimes

these five Oriental Churches are referred to as the non-Chalcedonian Eastern Churches.

However, the Oriental Churches cling to and affirm the Orthodox doctrine of the Trinity

as articulated in the first Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in A.D. 325 and confirmed by the

Second Council held at Constantinople in A.D. 387. In this sense the claim of these

Churches to the title Orthodox is justified. They are trinitarian. Furthermore, the

Oriental Churches also affirm Jesus Christ to be both divine and human, though not in the

language of Chalcedon.

Although the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is numerically the largest of the five Oriental

churches, it is little known in this country, both because of its remoteness and because

of the absence of any large immigration from Ethiopia.

However, in 1974, the first congregation of the Ethiopian Church in the western half of

our country was organized in the Los Angeles area. It now meets in Inglewood as St. Tekle

Haimonot. Abbott LM. Mandefro, the church's head priest for Canada, Jamaica and the United

States, presided at the founding ceremony. Only about 70 persons attended, but 28 were

baptized. At that time the total membership in the United States was estimated to be about

250 with another 200 in Canada.

Although obviously small in our area, the world-wide membership is about 20 million.

The group is affiliated both with the National Council of Churches in this country and

with the World Council of Churches.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church is of interest to historians and to sociologists of

religion because of its peculiar circumstances. As a result of its geography, its history

and its theology, it has been outside the influence of the mainline development of the

Christian religion and relatively isolated. As a consequence, it has developed its own

unique expression of the Christian faith.

This situation is similar to the fascination of zoologists in the fauna of places like

the Galapagos Islands, Madagascar and Australia. Evolutionary development in those

relatively isolated spots took its own course and resulted in some unusual features.

A brief survey of Ethiopian Church history reveals two major reasons for this

situation. First, as a result of the decisions of the Council of Chalcedon it, along with

the other Oriental churches, was out of favor and communion with both the Roman Catholic

(and subsequently Protestant) and also Greek Orthodox traditions. Hence it was insulated

from their influence. Secondly, the Moslem conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries

isolated Ethiopia from the political, economic and religious life of Europe. Islam swept

across north Africa and into Spain and dominated the Middle East where most of these

Oriental churches were located. Their numbers were decimated, they were forced on the

defensive and struggled merely to survive.

Three of the four great Patriarchates and centers of Christianity of the early church,

namely, Jerusalem, Alexandria in Egypt, and Antioch in Syria, suffered from the Moslem

conquests, and their power and creativity were checked. Only Rome escaped. Even the

territory of the Patriarch of Constantinople, the "second Rome," was reduced to

an island in the Islamic flood. Finally in 1453 it fell to the Muslims, and the Cathedral

of Saint Sofia became a mosque. Incidentally, ail of this contributed to the rise in

stature of the remaining Patriarch, the Bishop of Rome

It is generally understood that when any institution, whether church or nation or

ethnic tradition, is threatened, it tends to harden its patterns in an effort to maintain

its identity. It seeks to emphasize its distinctive forms, rituals and dogma. It resists

compromise and accommodation in order to affirm what it is and to reassure itself of its

existence.

This principle applies to all the Oriental churches and especially to the Ethiopian

tradition.

Let us begin by looking more closely at the theological isolation of the Ethiopian

Orthodox Church.

The Council of Nicaea, which had been convened by the Emperor Constantine in AC). 325,

was widely attended. All of the great Patriarchates were represented. Even faraway Britain

sent delegates. This Council defined the doctrine of the Trinity-and the deity of Christ.

This became the orthodox position agreed upon by all branches of the church.

The next major theological issue was how to describe the person and nature of Jesus.

Some identified ham so closely with God that his humanness became lost. For example, a

theologian named Eutychus likened his humanity to a mere drop of honey to be lost in the

ocean of his divinity. This position was unacceptable to the majority of Christians, who

insisted that Jesus was fully human. They did not want to lose completely the historical

Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels.

The result was two more Councils, one at Ephesus in A.D. 431 and the other in A.D. 451

at Chalcedon, a suburb of Constantinople. The Chalcedonian Creed, which resulted,

presumably settled the Christological problem with a curious formula. The heart of that

statement reads like this: ''Our Lord Jesus Christ Cast at once complete in Godhood and

complete in manhood, truly God and truly man . . . As regards his Godhood, begotten of the

Father before the ages, but yet as regards his manhood begotten, for us men and for our

salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the God-bearer, one and the same Christ, Son, Lord,

Only-begotten, recognized in two natures without confusion, without change, without

division, without separation."

Thus the Chalcedonian Creed affirms the doctrine of the two natures. One person, Jesus

Christ, possessed both human nature and a divine nature. Both the Jesus of history and the

Christ of faith were preserved for the followers of Chalcedon.

Both the Bishop of Rome and the Patriarch of Constantinople, and their followers,

accepted this formula. But Dioscurus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, and his associates,

including the Ethiopians, rejected it. They had difficulty envisioning one person with two

natures.

The position of Chalcedon was termed ''diophysite" meaning "the two

natures." Those opposed to the Chalcedonian formula were called

"monophysites" meaning one nature, i.e. Jesus Christ had only one nature--a

combined divine-human one. They conceded that before the Incarnation there were indeed two

natures--human and divine--but they maintained that in the Incarnation these two natures

were merged into one new nature or state, simultaneously human and divine. They could not

make sense of one person with two natures that were "without confusion, without

change, without division, without separation."

They also preferred to be called non-Chalcedonian rather than monophysite. So since the

fifth century, these non-Chalcedonian churches have been alienated from those who accept

the Chalcedonian statement.

That this ancient issue is still alive is evidenced in a visit I had with the Patriarch

of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Addis Ababa in 1972, before the Marxist revolution.

I had written to His Holiness, Abuna Theophilos, requesting an interview. I called his

office after my arrival in the city and a time was designated for a had- hour interview

two days later.

I had asked permission for Pauline to come with me, and, being uncertain as to the

place of women in Ethiopia and of the proper protocol, I explained that my wife was also

acting as my secretary. This somewhat devious duplicity could be technically justified,

inasmuch as, even today, Pauline types for me. Permission was granted, so we 60th were

there.

We arrived early and were ushered into a conference room to wait. Soon the Patriarch

arrived along with two of his bishops in full vestments and with an interpreter.

Through the interpreter, who spoke Amharic to the Patriarch, I thanked His Holiness for

the privilege of his time, acknowledged respect for the venerable tradition of the

Ethiopian Church and brought unofficial greetings from the low church Christians of this

country. Then I turned to my list of questions.

After a few inquiries about the number of worshipping groups and monasteries and

something about the current challenges facing his Church, I asked him whether Chalcedon

was an improper Council and whether he was disturbed that the diophysite churches of

Europe and America regarded him and other monophysite groups as heretics or schismatics.

At this point the Patriarch clearly became interested, the interpreter was ignored, and

he answered me at length in perfect English. The half-hour interview lasted an hour and a

had and was concluded when Abuna Theophilos ordered tea and cakes and presented both me

and Pauline with autographed copies of a volume he had edited in English on the history of

his church.

In the informal conversation that followed, I learned that he had lived for a time in

San Francisco and had travailed widely, lecturing and studying.

So much for the theological and ecclesiastical background of the Ethiopian Church. Let

us turn now to a brief sketch of its political and geographical isolation.

Christianity probably came to Ethiopia in the fourth century. Frumentius of Alexandria

had been consecrated as a bishop by the Patriarch of Alexandria, and he baptized the royal

family and ordained priests. Frumentius became known as Abuna Salama, "the Father of

Peace," and was the first bishop of Aksum or Ethiopia.

The Ethiopians like to point out that the conversion of their country to Christianity did

not require the blood of martyrs to be shed prior to that conversion, as was true of Rome

and many other areas. Christianity apparently was welcomed by people and ruler alike.

A curious feature of the relationship between the Patriarch of Alexandria and

Frumentius was that over many centuries all Ethiopian bishops were appointed in

Alexandria, and none was a native Ethiopian. Thus we have the phenomenon of an ethnic

church governed by an alien appointee. Often the bishop knew neither Geez, the liturgical

language, nor Amharic, the language of the people. This situation continued until the

present century.

Before the rise of Islam in the seventh century, Aksum was an extensive maritime and

commercial center. In its prime it ruled many districts in southwest Arabia across the Red

Sea. The rapid expansion of Islam changed all that. All important economic, political and

religious communications, both with the Byzantine realm and with Europe, were cut off.

Moslems moved across north Africa in the seventh and eighth centuries, sealing the

isolation of the area of Ethiopia. Only with the Alexandrian Church did Christian Ethiopia

maintain a very precarious contact.

The only significant break in the long centuries of political and religious isolation

came in the 16th century. Moslem states in the area began an attack. The nation appealed

to Portugal for aid. They knew the Portuguese possessed firearms.

The aid came, but a few years later the Jesuits also arrived. The king submitted to the

Church of Rome and nominally accepted the decree of Chalcedon.

However, this conversion did not penetrate deeply among the clergy and the people. A

later king expelled the Jesuits and reaffirmed the non-Chalcedonian faith.

Another long period of relative isolation followed, which lasted until the 1 9th

century. In 1855 Theodius II ascended the throne and began a policy of reintegration and

strengthening of the Empire, which had been torn by regional rivalries. One of his

successors, Menelik II, completed the process of administrative reform.

During all this time Ethiopia had escaped the colonizing policies of the several

European nations. While this preserved its independence, it also tended to emphasize and

to continue its separate existence and isolation.

The Italians had taken Eritrea, on the shore of the Red Sea, but when they attempted

the conquest of Ethiopia, they met a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Adwa in 1896.

Menelik II doubled the size of Ethiopia, established a new capital at Addis Ababa and

pushed the. modernization of his nation. The United States, along with many European

nations, recognized the sovereignty of Ethiopia and established embassies. Menelik

introduced a postal system, hospitals, printing presses, schools, roads and a national

bank.

In 1923 Ethiopia was admitted into the League of Nations. In 1930 RasTafari, the

leader, was crowned as Emperor and as the 225th Solomonic ruler. He took the name Haile

Selassie, which means "The Might of the Holy Trinity.

Part of the modernization of Ethiopia and its emerging national self-consciousness was

a renewal of the struggle for freedom from the domination by the Coptic Church of Egypt.

In 1929 Ras Tafari persuaded the Patriarch of Alexandria to consecrate five native

Ethiopian bishops. This was done.

Following the defeat of the Italians in World War 11, an accord was signed (1948) in

which it was agreed that on the death of the then Egyptian Coptic Abuna, his successor

would be an Ethiopian. However he would still be appointed by the Alexandrian Patriarch.

In July 1949 five more Ethiopian prelates were consecrated as bishops, and in 195t, for

the first time in Ethiopian history, a native Ethiopian, Abuna Basileos, ascended the

Metropolitan Seat. He was given the authority to consecrate bishops, and in 1959 he was

given the title Patriarch of Ethiopia.

In 1970 Abuna Theophilos succeeded him as Patriarch. Thus the Orthodox Ethiopian Church

finally obtained an autocephalous status similar to other Orthodox bodies.

Relations with the mother church of Alexandria have, however, remained cordial.

In concluding this paper I would like to list some of the features of the Ethiopian

Orthodox Church that establish and attest its uniqueness. Obviously some of these are more

significant than others, and some might even be regarded as trivial. But taken together

they display religious patterns found in no other tradition.

In general it might be said that many of the practices of the Ethiopian Church are

similar to those of the Greek Orthodox Churches. This is to be expected inasmuch as no

Renaissance or Reformation significantly influenced its practice. But they differ in a

number of respects.

The first item to notice is the presence of Judaic features which suggest a greater

Jewish influence. Of course Christianity in all its forms arose out of Judaism, but only

the Ethiopian tradition has retained, for example, the distinction between clean and

unclean meats, priestly dances with drums and reverence for Saturday, the Sabbath, as well

as for Sunday. Also each church possesses a so-called ark of the covenant. This is similar

to the ark of a Jewish synagogue where the Torah is kept.

Ethiopian tradition holds that the original Jewish Ark is now kept in a remote

monastery near Aksum 'the early capital. No reputable archaeologist or scholar has been

permitted to visit and inspect this shrine, so its authenticity has not been validated.

Most scholars are skeptical. Only one priest keeps the key to the shrine and no,one else

can be admitted. Before he dies, the priest must name his successor.

The Ethiopian Church practices circumcision, as do the Jews. It takes place eight days

after birth. However, the leaders of the Church, being familiar with the teachings of

Paul, insist that it is not practiced as a religious rite but merely as a custom of the

culture.

A second feature of the Ethiopian Church is its religious calendar. Its year consists

of twelve months of thirty days each. Five or six days are added at the end of the twelfth

month to adjust it to the solar year. Thus this calendar is not only pre-Gregorian. It is

pre-Julian.

Its chronology differs from that of the West in that it locates the year of creation at

5493 B.C. Since it teaches that Christ was born 5500 years after creation, about seven

years are added to our A.D. dates.

Also, according to its calendar, January 7 is the date for Christ's birth, and Easter

comes usually two weeks later than the Gregorian Easter.

Third, the Ethiopian liturgy is derived from that of the Coptic St. Cyril (or of St.

Mark) but differs in that it contains 14 Anaphoras (or "canons) instead of the usual

single canon. Its recitation requires at least two priests and three deacons. The common

frame for these Anaphoras is called the Ordo Communis and it never varies. The Anaphora

most frequently used is that of the Twelve Apostles. Others are used on certain special

saint days and in some monasteries.

Fourth, most of the Ethiopian Church buildings are round and contain three concentric

parts: the outer ambulatory where the hymns are sung, the nave where communion is

administered and the inner circle where the Tabot or Ark of the Covenant rests. However

some of the larger city churches and cathedrals have been built on the basilica pattern.

Women are admitted to the right side only, separated from the men. Generally, as in the

Orthodox tradition, there are no seats. Shoes must be removed when entering, although we

found that this tradition was not enforced in some churches in Addis Ababa.

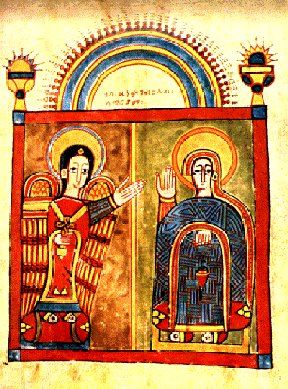

Fifth, the Ethiopian Cross is most frequently on the pattern of a Greek cross, but has

considerable elaboration with decorative designs. It is widely used in all services and

processions and is carried on a long staff. They use no crucifixes, as images are

forbidden, but icons are accepted.

Interestingly, the umbrella is also a religious object carried in processions. It is

not for rain or a shade for the sun but a mark of distinction. An orange umbrella is used

at funerals and a red one at weddings. The Patriarch is entitled to an umbrella with cloth

of gold and with a fringed border hung with silver crosses.

Sixth, the monks are of the Order of St. Anthony, the Hermit, but have accepted the

influence of Pachonius who first gathered the solitaries into enclaves, thus creating an

oxymoron, Colonies of hermits." Consequently each monastery is controlled by its

local abbot. This is more like the ancient Irish pattern than like the Benedictines or

others who are governed by a central authority and uniform rules.

Finally, the canon of the Ethiopian Bible differs from other recognized-collections.

Their New Testament contains 35 books: the 27 with which we are familiar plus an

additional collection of eight called the Sinodos. The titles of these are: Didascalia.

Epi~ment, Miracles-of ~lesus. History of Mary, Book of the

certain special saint days and in some monasteries.

Fourth, most of the Ethiopian Church buildings are round and contain three concentric

parts: the outer ambulatory where the hymns are sung, the nave where communion is

administered and the inner circle where the Tabot or Ark of the Covenant rests. However

some of the larger city churches and cathedrals have been built on the basilica pattern.

Women are admitted to the right side only, separated from the men. Generally, as in the

Orthodox tradition, there are no seats. Shoes must be removed when entering, although we

found that this tradition was not enforced in some churches in Addis Ababa.

Fifth, the Ethiopian Cross is most frequently on the pattern of a Greek cross, but has

considerable elaboration with decorative designs. It is widely used in all services and

processions and is carried on a long staff. They use no crucifixes, as images are

forbidden, but icons are accepted.

Interestingly, the umbrella is also a religious object carried in processions. It is

not for rain or a shade for the sun but a mark of distinction. An orange umbrella is used

at funerals and a red one at weddings. The Patriarch is entitled to an umbrella with cloth

of gold and with a fringed border hung with silver crosses.

Sixth, the monks are of the Order of St. Anthony, the Hermit, but have accepted the

influence of Pachonius who first gathered the solitaries into enclaves, thus creating an

oxymoron, Colonies of hermits." Consequently each monastery is controlled by its

local abbot. This is more like the ancient Irish pattern than like the Benedictines or

others who are governed by a central authority and uniform rules.

Finally, the canon of the Ethiopian Bible differs from other recognized-collections.

Their New Testament contains 35 books: the 27 with which we are familiar plus an

additional collection of eight called the Sinodos. The titles of these are: Didascalia.

Epi~ment, Miracles-of ~lesus. History of Mary, Book of the EPILOGUE

Two events, occurring in rapid succession last month, made it possible for me to write

this Epilogue, even though the paper itself had been finished.

First, on Friday, January 3, I attended an address by a retired missionary who had

served in Ethiopia for more than 30 years. He had lived there during the last years of

Haile Selassie's reign and into the Marxist period from 1974 to 1991.

Second, on the very next day, Saturday, January 4, I received in the mail a package

from Addis Ababa. It had been sent to me by the present Patriarch, Abuna Paulos, in

response to an inquiry of last July. It was a paperback biography of Abuna Theophilos

Written by his friend and companion, the current Patriarch. This booklet had been

published in July 1995.

These two sources enabled me to fill in the recent history of the church.

We know that the Marxist coup of 1974 had overthrown the monarchy of Haile Selassie and

that he had been executed. But it had been very difficult to obtain information about the

condition of the church during that period.

I learned that Mengistu Haile Mariam, the dictator, had seized Abuna Theophilos on

February 7, 1976. The Patriarch endured harsh treatment and imprisonment. On July 14, 1979

Theophilos had been taken from prison to be executed. His death and burial spot had been

hidden for 13 years.

In May of 1991 the rebel forces captured Addis Ababa and Mengistu fled to Zimbabwe.

In July 1991 the search began for the grave of Theophilos, and in April 1992, with the

aid of eye-witnesses, his burial spot was located.

On July 12, 1992, in a colorful ceremony, his remains were removed from the unmarked

grave to the Mekane Hyawan St. Gabriel Cathedral, where they rest today.

The ceremony was attended by representatives of the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic,

Evangelical and Anglican Churches.

At the close of the service, Abuna Yaicob, the acting Patriarch, read the following

statement:

"It is decided by the Holy Synod of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church that

from this day onward, His Holiness, Abuna Theophilos, shall be called "Martyr of the

Church, because he was martyred by the brutal Dergue communist regime for his firm~stand

in safe guarding and protecting the right and honor of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido

Church."

Thus one more saint has been added to the long list of Christian martyrs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abuna Paulos Brief History of His Holiness. Abuna Theophilos before and after his Visit

to the Western Hemisphere. Addis Ababa, July 1995.

Abuna Theophilos, ed. The Church of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, 1970.

Chatfield, Lei "Timeless Ethiopia" International Travel News, June 1944.

Coffey, Thomas M. Lion By the Tail. Viking Press, N.Y., 1974.

Eadie, Douglas G. "Chalcedon Revisited." Journal of Ecumenical Studies,

Vol.10, No. 1.

Eliade, Mercea "Ethiopian Church." Encyclopedia of Religion, Macmillan, N.Y.,

1987.

Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. 8, "Ethiopia." Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.,

Chicago, 1955.

Gerster, George "Searching Out Medieval Churches in Ethiopia's Wilds."

National Geographic, ca 1970.

Los Angeles Times March 23, 1974, Part I, page 27; June 9, 1992, Section H. page 1;

February 9, 1993, Section H. page 3.

|