|

The Air Minded Mission Inn

Steve Spiller

Redlands Fortnightly Club

Meeting #1790

Thursday, February 18, 2010

The Airminded Mission Inn

Introduction

Visitors to the Glenwood Mission Inn often thought they had stepped into one of Father Serra’s hallowed missions, despite Riverside’s inland location nearly 50 miles from the “King’s Highway.” Featured throughout the hotel were Madonna and child paintings, stained glass, saintly statues, and other ecclesiastical items. Artifacts filled basement spaces named the Refectorio, El Camino Real, La Rambla, and Santa Clara Chapel and guests purchased rosaries and other religious objects in the Cloister Art Shop. There was more. Master of the Inn Frank Miller’s tendency to dress in padre’s robes did little to dissuade an unsuspecting visitor.

The hotel was and is more than an adaptation of a California mission. It is a study in architectural diversity. Spanish, Moorish, Middle-eastern, and Asian inspired designs were integrated with the Mission Revival. In one outdoor area, it is easy to imagine a plaza in Seville or at the Alhambra. A pagoda-capped chimney, foo dogs, and an enormous incense burner might cause one to wonder if they were in Kyoto. The Kiva and Hogan rooms provided another layer, as did the Lea Lea Room, which opened in 1939; the latter popular among Army Air Corps pilots and crews who frequented the South Seas inspired watering hole.

The stuff filling the five-storey hotel reflected a world embraced by Miller and his family. Their passion for travel and collecting habits resulted in the acquisition of crosses, operatic souvenirs, dolls, cream pitchers, and bells. Wrought iron railings purchased in Spain were installed along 7th Street and della Robbia plaques cemented on walls. Plein air landscapes, coats of arms, candlesticks, and the oak arts and crafts furniture of Stickley, Limbert, and Elbert Hubbard’s Roycroft community added to the guest experience. Miller created rooms to hold the collections. Architect Myron Hunt’s Spanish Art Gallery, emulating the great Baroque galleries of Europe, housed Mexican and Spanish colonial art. On display in the Hogan and Kiva were Native American arts and crafts. The Fuji Kan Room and Hall of the Gods held a variety of Asian religious iconography, gongs suspended from red lacquered stands, lanterns, decorative pottery, and other items from the Far East. Decades before Disney created “It’s a Small World,” the Mission Inn’s world-view attracted visitors by the hundreds and led one writer to declare,

This place is indeed so richly, stupefying of wonders as almost to defy description . . . But it has the power to amaze and stagger the mind . . . If you could see just one building in Southern California, this would be the one . . . it is full of care and love

and imagination and. . .as full of panache as any building around. . .The place has

to be fully described, because its fullness is its point.

The Airminded

Despite looking to the past for inspiration, the advent of manned flight took on enormous significance at the Mission Inn. Frank Miller’s only child, Allis Hutchings, her husband DeWitt, and their three children, Frank, Helen, and Isabella embraced flight with an unmatched enthusiasm. They believed in “airmindedness” or being “airminded,” terms that found their way into the country’s consciousness in the early twentieth century. In a 1934 letter Allis wrote, “My father, Frank Miller is owner and builder of the Mission Inn, a hotel over fifty years old. He is a great advocate of peace, and, of course, is very inter-nationally minded. . .Father believes that aviation can be a means to bringing the world closer together in more friendly relations, which adds greatly to our enthusiasm for aviation.”

Aviation provided hope for mankind. The Women’s International Association of Aeronautics adopted the phrase “Wings around the world for peace, prosperity, and world friendship.” Aviators were “messengers” or “prophets” capable of reaching the heavens. Achievements such as Charles Lindbergh’s 1926 Atlantic crossing inspired clergy, poets, and artists, packed the nation’s newspapers, and inspired young, future aviators. Stanford professor Joseph Corn referred to the airminded in his book The Winged Gospel, “Americans widely shared Parker’s

(. . .the) notion of the airplane as a messiah. They never considered the flying machine simply as way of moving people or things from one spot to another. Rather, it seemed an instrument of reform, regeneration, and salvation, a substitute for politics, revolution, or even religion.”

The public flocked to air shows and barnstormers landed in the nearest wheat and alfalfa fields. The American Society for the Promotion of Aviation pressed for the construction of airfields “in every city and town in the country.” Schools embraced an integrated aviation “Air-Age Education.” Model building became the rage. Contests sponsored by radio stations and department stores inspired construction of the tissue paper, dope, and balsawood winged replicas. The Jimmy Allen Flying Club and the Junior Birdmen of America enthused America’s youth. Toy companies received praise for the “design and workmanship” of their aviation toys, toys intended to “teach the child the fundamental principles of flying.” As World War II ended, manufacturers of private planes considered the thousands of military pilots leaving the armed forces potential customers. Some envisioned a “plane in every garage” for “highways in the sky.”

Fueling the airminded passion of “Riverside’s air ambassadors” was, in part, the proximity of the Army Air Corps’ March Field. At one point, the offices of the base commander were located in the Mission Inn. Frank Miller, California Governor Hiram Johnson, and others worked hard to ensure the new airfield was located in Riverside. Alessandro Field (later named March Field) opened on March 1, 1918. Miller and his wife’s signatures are on the deed officially transferring the 640 acres to the United States government in June 1919 for $100 per acre.

In the 1920s, the U. S. military initiated a building program to replace the hurriedly built bases and posts constructed during World War I. The military adopted city planning principles and historic architectural styles in an effort to improve shabby conditions prevalent at many of its facilities. Myron Hunt was selected as the architect for the March Field project thanks to Frank Miller’s recommendation. Colonel Francis Wharton, Chief of the Engineering Department, stated that, “the quarters and barracks (at March Field) will recall to their occupants the peaceful simplicity of those other missions along the Camino Real.” The government dictated that the style of the base was to, “harmonize with the best traditions of the historical architecture of Southern California.”

Construction contracts awarded in 1928 for March Field exceeded $1,000,000. Work began the following year. Hunt used a hollow-wall concrete system for the massive project of barracks, officers’ quarters, hangers, chapel, radio hut, parachute and armament buildings, and miscellaneous structures. The clay tile roofs and hollow-wall structures mirrored Hunts’ community hospital projects in Artesia, Upland, Redlands, and Riverside in design and materials.

World War II brought the connection between March Field and the Mission Inn even closer and the Inn’s revitalization resulting from the influx of servicemen into downtown Riverside. The 4th Air Force located their offices opposite the hotel in the old post office building. The Inn was an off base unofficial “officer’s club,” probably because only officers could afford the rates despite war-imposed rent controls. Overnight accommodations in Riverside were at a premium and overflow was difficult to handle. On at least one occasion, the Fox Theater, at Market and Seventh Streets, became makeshift living quarters. Following the evening’s last show, soldiers bunked down in the loge seats, on lobby couches, and wherever they found space.

Minutes from weekly hotel staff meetings reveal fewer fresh flowers and the elimination of sauces on vegetables, implementation of air raid and blackout procedures, and the donation of cannon for scrap metal. Hotel management introduced a policy forbidding employees from asking military personnel about arrivals, departures, and lengths of stay.

A B-29 assigned to the 22nd Bombardment Group stationed at March maintained a singular relationship with the hotel. Although scantily clad pinups were the norm for nose art during World War II and Korea, other subjects found favor. Pictured on the side of the B-29 was a bomb falling from the sky as a man hastily ran toward a sign reading “North 38th Parallel.” Above the image was the name “Mission Inn;” the play on words obvious. On July 4, 1950, the 22nd deployed to Okinawa just days following the outbreak of the Korean Conflict. They completed seventy-seven missions over North Korea before returning to the states in October 1950.

Advances in aviation travel provided many adventures for the Hutchings’ family. In December 1936, they flew to South America on a four-week journey. On this trip, “The Hutchings expect to make contact with noted aviators and other leaders in the southern hemisphere. . .” They were some of the first to fly on the Pan-American Clippers manufactured by Sikorsky, Martin, and the Boeing companies. Frank Miller Hutchings provided an interesting account of one episode on the family’s trip. In an article published in February, 1937, Hutchings’ reported, “Suddenly, without warning, the plane went into a terrific ‘nose’! We fell to the floor in mass, laughing.”

The Hutching family’s airmindedness inspired the creation of the International Shrine of Aviators. Looking to the past, they turned for inspiration to the 11th century St. Francis of Assisi – founder of the Franciscans and patron saint of animals. They dedicated the Shrine on December 13, 1932 proclaiming St. Francis the Patron Saint of Birds and Birdmen. The St. Francis Chapel was completed the previous year. Riverside architect and builder G. Stanley Wilson made use of the Churrigueresque Spanish Baroque design found on the Casa de Prado in San Diego’s Balboa Park and the Myron Hunt designed Riverside 1st Congregational Church. At the chancel’s front is a gold leaf reredos from Mexico and seven Louis Comfort Tiffany windows pulled prior to demolition from the Stanford White designed Madison Square Presbyterian Church in New York City. Allis wrote, “In our newest wing is the St. Francis Wedding Chapel which has been dedicated as the International Shrine to Aviators. We are not a religious institution in any way, but a hotel that is different and where many people come to be married.”

The aviation theme was prevalent throughout the chapel. Displayed in several shadow boxes set into the paneling just inside the massive red mahogany doors, were nearly 600 aviation insignia. Hanging nearby was a painting providing an uncommon interpretation of manned flight. The painting titled “St. Francis and the Flying Cross” depicts a crucifix in flight above the Franciscan’s head. Inscribed on a watercolor displayed in the chapel was the following,

St. Francis of Assisi

the Patron Saint of Fliers

my death Brother Eagles – you are much

beholden to God, your Creator. He has

given you liberty to Fly about in all

places and has appointed for you

the element of Air

Many young airmen stationed at nearby bases and their brides chose the Mission Inn for their weddings. Couples with an aviation connection signed a register set aside exclusively for them. Many young airmen stationed at nearby bases and their brides chose the Mission Inn for their weddings. Couples with an aviation connection signed a register set aside exclusively for them. It was no ordinary wedding register, but an eight-foot long propeller housed in a large wood and glass case. A young officer and future general, Murray Bywater and his bride Frankie Galloway, signed the CS Storey manufactured propeller on July 2, 1941. Col. John Theron Coulter and his wife, actress Constance Bennett, added their signatures on June 22, 1946. There was little room for additional signatures when in 1947 DeWitt Hutchings wrote a colonel at March Field seeking a new propeller. Couples also signed their names in a traditional book-like register. Pelma Padgett, the future Mrs. Alfred Lawrence Way, created a new tradition when she planted a kiss alongside her signature. The spontaneous action inspired others. Feminine lip prints liberally adorn the register’s remaining pages for 1942 and all of 1943. Despite the war and limited supplies, cosmetic companies offered lipstick in several shades. Patriot Red, Commando Red, and Victory Red were popular shades available to American women promising “long-lasting freshness” and “the most exciting, flattering lip-reds ever created.” Sixty-eight years have passed since Pelma planted the first kiss. The red prints remain surprisingly vibrant.

DeWitt Hutchings created a coin-like good luck piece. On one side was an image of St. Francis kneeling in front of the chapel offering his hand to the birds and on the reverse the following adapted from a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem titled The Sermon of St. Francis,

St. Francis Patron Saint of the Birds Protect the Men that Fly

He giveth you your wings to fly and

breathe a purer air on high and careth

for you everywhere, who for yourselves

so little care.

Allis and DeWitt enclosed the good luck pieces in letters soliciting additions to the “International Collection of Aviation Insignia and Badges.” They mailed solicitations to individuals, airlines, the military, fellow collectors, representatives of foreign governments, and many others. In a letter to a president of the Air Lines Pilots Association, DeWitt wrote, “‘Hap’ Arnold and Jimmie Doolittle and many more kept our good luck piece with them always during the war. We hope you may keep this one always with you.”

The couple’s efforts were a “worthy cause of international friendship” and foreign visitors to the Mission Inn were “always anxious to have their countries represented.” Allis noted, “The collection is in the form of winged insignia, either metal or embroidered, as worn on the brest [sic] of the pilots’ uniforms or on their caps; or metal broaches or pins or medals or badges that have to do with flying.” Two of the notable insignia include the “Hat in the Ring” pin from the 94th Aero Squadron and a Zeppelin Hindenburg badge. A 3-ringed binder containing the multi-page list of insignias hung from a string for visitors to peruse.

To the left of the St. Francis Chapel is a small area protected by a wrought iron fence and gate. Within are 154 copper wings mounted on the cast concrete walls. Each set of wings is approximately 19 ½” wide by 13” in height. Dedicated in 1934, the Famous Fliers Wall is a mixture of showmanship and a genuine love of aviation, and provided one more thing for visitors to experience at a hotel that was, to many more museum than a place to lay one’s head. Featured on the majority of the copper wings are the honorees etched signatures and the date of the wing ceremony. The source of copper for the first wings reportedly came from a still confiscated by the Riverside County Sheriff.

Of the 154 fliers, groups of fliers and notable aviation enthusiasts some are better known than others, but each made significant contributions to the world of manned flight. Hap Arnold, Chuck Yeager, Jimmy Doolittle, Hoyt Vandenberg, Orrville Wright, Jacquie Cochran, Glen Martin, John Northrup, Ed Sholl, Matilde Moisant, and Curtis LeMay are a small minority of those honored. The WASPs, Medal of Honor aviators, and astronauts John Glenn, Michael Coats, and Buzz Aldrin are among the acknowledged. A barbed wire wrapped wing honors the POW and MIAs. Even if one’s wings are not on the wall, there is a sense of community, a community of fliers – not all military and certainly, not all men.

Two days after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and the other Pacific locations, Captain

Colin P. Kelly, Jr. died saving his B-17 crew returning from a bombing raid in the Philippines. Kelly and his family had lived near the Mission Inn on Brockton Street from 1939 – 1940. The 26-year old officer served in the 32nd Bombardment Squadron headquartered at March Field. Kelly became the 55th Famous Fliers’ Wall recipient. The ceremony was on April 12, 1942, but the wings are dated the day he died. Kelly was one of twenty-three Fliers’ Wall recipients honored during World War II.

The Mission Inn, as expected, became the repository for aviation related objects. According to professor Corn, “Over the years, the collecting of aviation relics became common, a form of airplane worship analogous to the reverence for relics shown by traditional religions. . .To the airminded even the tiniest remnants that could be linked to the miracle at Kitty Hawk, or to any important flight, took on symbolic importance.”

A room christened the “pilots roost” housed many of the family’s aviation relics. Sand from Kitty Hawk, a scrap of fabric off a Wright Brothers plane, the gas gage from Sir Charles Kingsford Smith’s Southern Cross, a Charles Lindbergh bust, a leather aviator’s cap, photographs, and an original program from the January 1910 Los Angeles air show remain part of the collection. Col. Roscoe Turner, a participant in the 1935 MacRobertson Air Race from London to Melbourne, presented several items to Mr. and Mrs. Hutchings in June of 1936. Glenn Martin gave a strut from the China Clipper and General Oscar Westover furnished a flag from a stratosphere balloon. The gathering of aviator’s signatures was commonplace among collectors. A cream-colored leather vest made from women’s kit gloves stitched together features the names of 40 or more aviators, including Famous Fliers’ Wall recipient Ruth Law. In 1948, DeWitt received a letter, in which the author wrote, “Last Easter I spent an enjoyable Sunday at your place. Your aviation display naturally interested me as I am an old time balloon and airplane pilot myself. I am a member of the “Early Birds” and took a rotary aircraft off the ground in 1913.”

Another well-known collector of aviation relics was Mrs. Mary E. Tusch. She lived near the United States School of Military Aeronautics on the Cal Berkeley campus. Cadets frequented her Union Street home labeled The Hanger, Shrine of the Air. “Mother Tusch’s” collection included photographs, news clippings, correspondence, and “relics.” On display was a piece from the destroyed Hindenburg. Charles Lindbergh, Eddie Rickenbacker, Richard E. Bryd, and hundreds of other aviators enthusiastically accepted Mother Tusch’s invitation to sign her living room walls.

The aviation related materials in the Mission Inn collections include many objects and documents that in the minds of aviation enthusiasts and the public are pivotal to the early development of aviation. These items are the stuff inspiring movies and books, and leading to unsolved mysteries.

Zeppelin

A friend of Allis Hutchings, British aristocrat and journalist Lady Grace M. Hay Drummond-Hay, wrote for the Hearst newspapers, The New York Times, and the North American Newspaper Alliance. When she stepped aboard the Zeppelin Hindenburg for the May 1936 maiden voyage, the journalist was already a seasoned airship traveler with 50,000 miles “under her belt.”

In 1929, Lady Drummond-Hay embarked on a round the world flight aboard Dr. Hugo Eckener’s Graf Zeppelin. The LZ-127 trip electrified the world, frightened and alarmed others, and cast mammoth shadows upon the land. The airship had nearly completed the 28,000-mile trip on May 25 when it reached the California coast and a colorful sunset over the Golden Gate. The ship proceeded south to Los Angeles in the dark of night. As it glided over San Simeon, the trip’s financial backer, William Randolph Hearst flooded the ship in light. Further south, a throng estimated at ½ million crowded the Los Angeles Municipal Airport to welcome the world travelers. An inversion layer above the city nearly prevented the zeppelin from landing at Mines Field the morning of May 26. It came within three feet of high-tension wires on departure. We do not know if DeWitt and Allis were among the half-million there to witness the ship’s appearance. In the Mission Inn collections is a small glass bottle of Veedrol oil with a cork stopper and a cardboard tube with a screw lid. Printed on the label is “Graf Zeppelin.” Identical samples are in San Bernardino County Museum and University of Oregon collections.

Readers of The New York Times eagerly tracked Lady Drummond-Hay’s daily dispatches as the Hindenburg left Germany crossing over Cologne, Holland, Dover, and the Isle of Wright before heading out across the Atlantic. The 61 ½-hour voyage ended May 9, 1936 without mishap at the Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey. Nine days later Lady Drummond-Hay arrived at the Mission Inn for a brief overnight stay. DeWitt and Allis hosted a congratulatory dinner following a wing ceremony honoring the journalist. Among the dinner guests was their son, Frank Miller Hutchings. One can only imagine the reaction and thoughts going through the mind of the adventurous 26-year-old grandson of the Inn’s founder and the other 18 attendees as they sat mesmerized listening to the lady journalist speak. Two years earlier Allis presented Lady Hay a St. Francis good luck piece. Prior to the departure in Germany, the journalist shared with fellow passenger Father Paul Schulte the story behind the medal. She noted, “I carried it constantly, as I have always been an admirer of the characteristics of St. Francis. . .” The priest blessed her medal. A review of Lady Hay’s New York Times dispatches provides clues to the account she shared with those at the evening’s festivities. To the amazement of first time travelers aboard an airship, there was little or no feeling of flight, no motion; far different from other modes of transportation. Several passengers on the maiden flight stayed up not wanting to miss any part of the experience despite the fine sleeping accommodations. They watched “the moonlight shimmering off the ocean a thousand feet below.” The timing was perfect. On May 8, a full moon illuminated the Atlantic night. Passing between two enormous icebergs in the North Atlantic caused a bit of a thrill for the passengers. Paul Schulte, nicknamed the “flying Padre,” performed the first ever Mass in flight on May 8 above the Atlantic in full vestments in front of a temporary altar absent lighted candles. Other activities aboard included a voice and piano concert featuring Schubert’s Serenade and I’m in the Mood for Love. The Los Angeles Times quoted Lady Hay saying, “It’s the ideal way to travel with all the comforts of the best appointed hotel, including electricity and hot and cold water.” The lady journalist shared one criticism with Dr. Eckener and Captain Ernst Lehmann; there were no full-length mirrors aboard the Hindenburg.

Six months later Frank Miller Hutchings shared his experiences as a passenger on the 803-foot airship, the final east to west voyage of 1936. The $400 one-way flight docked at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station on October 7, 1936 and Frank flew to the West Coast on board an American Airlines “Sleeper.” Articles appeared in the local press following his return, “Hutchings Makes Speedy Journey – Riverside Young Man Was Passenger on Famous Zeppelin Line” and “Rapid Travel By Air Told In Club Talk.” He would later say that “the voyage was notable for its lack of excitement, its smoothness and the respect tendered both officers and crew.”

In the insignia collection is the Hindenburg badge Frank presented his mother. The badge is one of several airship insignia in the collection, including a U.S. Army Air Corps Airship Pilot badge. Another Hindenburg object in the collection is a brochure promoting the joint venture between American Airlines and the Hindenburg Company. Clearly visible in the airship photograph on the brochure cover is the Nazi flag on the lower and upper portions of the airship’s tail. The symbol first appeared on the German airships in 1933. Minister of Propaganda, Josef Goebbels initially ordered the equilateral cross painted on the side of the Graf Zeppelin. However, on other German aircraft, the symbol appeared on the tail. Tradition ultimately triumphed.

During the winter, the Hindenburg underwent a complete overhaul, additional cabins added, the four diesel engines modernized, and new propellers installed. On May 3, the ship departed Germany for the United States. On May 10, the American public heard sorrow and absolute despair in Herbert Morrison’s recorded voice as he reported on the horrific landing at Lakehurst on the previous day. “It's crashing. . .This is the worst of the worst catastrophes in the world. . .All the humanity and all the passengers screaming around here. . .I can't even talk to people whose friends are on there. Oh, I can't talk, . . .”

The Riverside newspapers turned to Frank Hutchings for his reaction,

That the epoch-making greyhound of the skies, Airship Hindenburg, is now no

more, comes as a gruesome shock to all air-minded Americans. To any of the

several hundred passengers who have spanned the Atlantic by zeppelin, the

loss comes as an even more poignant blow. I, speaking as a passenger looking

down upon the Lakehurst ground crew, now how horrible must have been

those last few seconds of yesterday’s mooring.

Frank’s faith in air travel remained high, “I feel sure that those who last night failed to reach the hangar would repledge their faith that the conquest of the air shall continue.”

Amelia Earhart

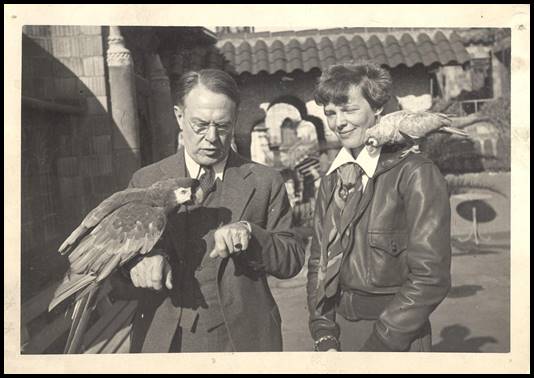

Sixteen women are among those honored at the Famous Fliers’ Wall. They include Ruth Law, Louise Thaden, Laura Ingalls, and Amelia Earhart. On February 3, 1936 Earhart, her husband George Putnam, and fellow female pilot and Fliers’ Wall honoree Blanch Noyes attended Amelia’s wing ceremony. Apparently, no photograph of the actual ceremony exists. An iconic image taken that day shows Earhart with DeWitt Hutchings, the Inn’s pet macaw Napoleon, and a smaller parrot. The latter is perched on Earhart’s leather flying jacketed shoulder. Other images from the February 3 event are in the George Palmer Putnam Collection in the Archives and Special Collections of the Purdue University Library. Close ties existed between Earhart and the university. In 1935, she accepted an appointment as a counselor in the school’s careers for women department. Purdue provided the financing for Earhart’s $80,000 twin engine Lockheed Electra “Flying Laboratory.” George Putnam donated a significant portion of the existing collection in 1940 and his granddaughter provided additional materials in 2002. Access to the collection is limited. Scans of over 3500 objects and archival materials are online, including several items germane to the Mission Inn collections.

Two months prior to the Hindenburg disaster, Earhart, technical advisor Paul Mantz, and navigators Harry Manning, and Fred Noonan left Oakland aboard the aluminum twin prop on the first leg of the west to east trip round the world. Half way between the California coast and Honolulu, the right hand propeller froze solid. They landed without incident at Wheeler Field on March 18 with Mantz at the controls. The reception committee there to greet the four included Brigadier General and Mrs. Barton K. Yount. Yount commanded the 18th Composite Wing at Fort Shafter, the Army’s senior Hawaiian headquarters. He previously served as commander of March Field for two years during its infancy, beginning in 1919.

Upon Earhart’s arrival, mechanics removed and disassembled the right hand propeller. They found the problem “to have been caused by the lack of and use of improper lubricant” prior to the Oakland departure. Refueling the Electra in preparation for the flight to Howland Island provided challenges. The Standard Oil gasoline pumped in contained “considerable sediment” necessitating refueling with Army Air Corps fuel. Rather than take off from the Wheeler Field sod airstrip, Mantz selected the 3,000 foot paved runway at Luke Field on Ford Island for the departure. Earhart taxied onto the runway at 5:45 am the morning of March 20, 1937. On board with her were navigators Manning and Noonan. At the end of the runway the plane turned and, “as the airplane gathered speed it swung slightly to the right. Miss Earhart corrected this tendency by throttling the left hand motor. The airplane then began to swing to the left with increasing speed, characteristic of a ground loop.” The plane was on one wheel with the right wing tilted low to the ground when the landing gear collapsed. It slid “on its belly. . .amid a shower of sparks.” There was no fire and no one was injured. The same day Earhart, Mantz, Manning, and Noonan boarded the Matson liner Malolo for the unplanned return to California. On March 26, the disassembled plane was loaded on the SS Lurlin for shipment to Lockheed’s Burbank facility.

On a recent episode of the popular PBS program “History Detectives,” a US Army veteran’s family believed a jagged piece of aluminum in their possession was from Earhart’s Electra. The family contacted the programin an effort to verify the story. The ensuing investigation confirmed the piece was from the plane’s main landing gear. In the holdings of Cleveland’s International Women’s Air and Space Museum is a second piece of aluminum, this one later made into bookends. Written on yet another scrap of twisted metal is the following, “From the Flying Labatory Lockheed damaged Honolulu, March 1937 Amelia Earhart presented by Brig. Gen Yount #55.” The latter is one of several Earhart related objects in the Mission Inn collections. Other items include a Lukenheimer fuel filter off the Electra and an Amelia Earhart doll belonging to Helen and Isabella Hutchings. A 7 ½ foot long yellow windsock and a weathered grey chunk of burnt driftwood are also linked to the woman aviator. DeWitt Hutchings reported in 1948 that, “we have several things of Amelia Earhart including the windsock that was flying for her on Howland Island.” A thumbtack stuck into the driftwood holds a tiny scrap of paper once part of the description label acknowledging the wood came from a signal fire. If we had the entire label, then we would know if the driftwood and windsock were from Earhart’s 1st attempt to reach the island or later, on July 2, 1937.

Earle Lewis Ovington

In the Mission Inn Foundation and Museum’s archives is a photography collection labeled Aviation Photo Album No. 1, Earle L. Ovington, Newton Highlands, Mass. Within the simple album are more than 250 images dating from 1910-1911. They reveal an extraordinary period in aviation history at a time when a license took little time to achieve, and death in a flying machine although not a certainty, was commonplace.

Earle Ovington was an accomplished photographer; a skill he frequently used documenting his college career at MIT. It was common for him to be in his own photographs, having pulled the cord capturing the image on a glass plate. The cord was not long enough for Earle to pull as he flew his Bleriot monoplane Dragonfly above the Massachusetts State House on June 15, 1911 or at the Chicago International Aviation Meet two months later where he earned $6,009.63 in prize money. Other photographers were there to capture these historical events.

The young man was bright and ambitious with an inventor’s mind. Forced to delay his education due to family financial need and still a teenager, Earle secured a job as a laboratory technician with the Edison Electric Illuminating Company. He left Edison’s employment to enroll at MIT in 1900. Class work included analytical geometry, mechanical drawing, physics, chemistry, and electricity theory. In 1902, two years before he graduated, Earle joined with Dr. Frederick Finch Strong in developing the Strong-Ovington Static Induction and High Frequency Apparatus used to treat patients with the electrical high frequency currents. Earle sold his first Ovington Manufacturing Company X-ray machine to Massachusetts General Hospital in 1904.

Earle had other creative, scientific, and commercial interests. He founded the Ovington Motor Companies, held patents on motorcycles, was an early importer of motorized bicycles, and became the second president of the Federation of American Motorcyclists – all before the age of 32. His initial interest in aviation may have resulted from a friendship with fellow motorcycle enthusiast Glenn Curtiss. Two images taken at a 1910 air show reveal Earle’s eagerness to fly. The photo captions read “Getting the Fever” and “Why Can’t I Fly.”

On December 10, 1910, the young scientist and entrepreneur boarded the SS Minnetonka headed for France. Earle Lewis Ovington was off on a new adventure. Meanwhile in France, Louis Bleriot, aeronaut and designer, crossed the English Channel on July 29, 1909. The French aviator would own his own airplane manufacturing company and establish flying schools in France and England. In 1911, there were only 26 pilots in the United States as compared to 353 in France, 57 in Britain, 46 in Germany, 32 in Italy, and 27 in Belgium. Traveling to Europe for flight training was essential.

Ovington attended Bleriot’s flying school in the south of France. The student referred to himself as an “embryo birdman” and “grass cutter.” On January 20, 1911, after 8 lessons, Earle earned his flying license. The newly licensed pilot returned to the United States with a 70 Gnome Bleriot monoplane. On board the return ship, he met his future wife, Adelaide Alexander. Within days of docking in New York City, the couple married.

Ovington wasted little time getting into the air upon returning from France. He participated in at least six air shows between May and October of 1911, including Belmont, New York, Columbus, Ohio, Waltham, Massachusetts, Chicago, and Nassau, New York and a failed attempt to fly across the country. His wife Adelaide recalled in the book she wrote titled An Aviator’s Wife, that she labored “for many an hour pasting in press notices about his flights” in a huge scrap book. Perhaps she also compiled the photo album.

Airplane design was in its infancy in 1911. The styles and type of aircraft pictured in the album vary widely and include monoplane, bi-wing, and tri-wing. Those pictured in the album are many of aviation’s pioneers - Glenn Curtiss, T.O.M. Sopwith, Louis Paulhan, Octave Chanute, Louis Bleriot, Santos Dumont, Harry N. Atwood, Eugene B. Ely, and Earle Lewis Ovington. The absence of the Wright Brothers may have to do with a series of lawsuits they filed against Curtiss and others claiming patent infringements.

An event on September 23, 1911 secured Earle a spot in aviation history. He was one of 37 aviators participating in the International Aviation Tournament on Long Island. He had the exclusive opportunity to transport US mail. Following the required oath, Earle took a 75-pound canvas bag from the US Postmaster Frank H. Hitchcock. He then flew ten miles with the bag balanced on his lap. Rather than land with the mail, he dropped it over the side; the contents scattering over the ground. The first airmail flight was history.

Ovington gave up exhibition flying before the year ended. He lectured and wrote about flying, started a flying school, participated in the development of seaplanes in World War I, and served as director of an exclusive camp in Rhode Island for the daughters of the well-to-do. Earle was a founding member of the Early Birds aviation club and its president for a time. Southern California beckoned. The family arrived in California in 1920 and three years later moved to Santa Barbara. Earle turned his attention to land development creating a subdivision he named “Casa Loma” in the north part of Santa Barbara. He also built an airfield, “openly defying the ordinance which would ban him from operating an air field in a residential district.” Four years later Ovington died at the age of 56; his early work with X-ray photography considered a contributing factor in his death. In 1969, Santa Barbara named the terminal at the municipal airport in his honor.

A Massachusetts antique collector discovered a collection of glass negatives belonging to Earle Ovington. The discovery led to the research and publication of a fascinating exploration of Ovington’s life. The 432-page book, published in 2009, titled Reminiscences of a Birdman contains over 650 photographs. Author Robert D. Campbell conducted exhaustive research tracking down Ovington family members with original materials and locating other Ovington objects at the Henry Ford Museum, including Earle’s cork crash helmet, altimeter, and map case. The book contains duplicates of several photographs in the Ovington album. Scholars know their published research can result in the discovery of related materials, sometimes years after they complete their work. Robert Campbell completed his biography of Ovington unaware of Aviation Photo Album No. 1 in our collection.

Cal Tech, the Huntington, and UCLA are three of six institutions in the state, not including the Mission Inn, with searchable finding aids for their Ovington materials through the Online Archive of California. A sample search for “zeppelin” on the statewide website revealed significant resources among California repositories. Finding aids for forty-three collections in eleven of over 250 participating institutions are accessible to researchers interested in airships. In addition, institutions with online digital images of actual artifacts, documents, and photographs allow researchers opportunities to access collections long distance. A case in point is the Purdue University collections.

The Mission Inn Foundation received an Institute of Museum and Library Services Technology Grant in 2004 for the development of an object-based website including curriculum for grades three through twelve. The collection was divided into eight modules or themes with 10 primary objects selected for each theme: Architecture, California Missions, Cultural Diversity, Citrus Culture, the Miller Family, Art and Artisans, Movers and Shakers, and Aviation. Objects featured in the Aviation module include the scrap piece of aluminum from Earhart’s plane, the Graf Zeppelin bottle of oil, and images from the Ovington photo album. Although the Mission Inn Foundation is currently not an Online Archive of California participant, future researchers, like Robert Campbell, will have remote access to the collections long distances from California.

Conclusion

Airminded followers turned their attention elsewhere as the first half of the 20th century came to a close. Achieving peace, prosperity, and world friendship through aviation did not occur, especially following the outbreak of world war. There was little effort to put a plane or helicopter in “every garage” despite extraordinary sales of private planes in 1946.

Meanwhile the Glenwood was tired and growing old. Business declined after World War II and even more so, after Korea. No longer were Air Corps officers billeted at the Mission Inn or the Lea Lea Room filled with soldiers from the surrounding bases. Preventive maintenance was a necessity, but not a priority. Frank Miller’s only child, Allis, died in 1952 and four months later, her husband of 43 years was dead. The grandchildren, Frank, Helen, and Isabella Hutchings, sold the Inn to Benjamin Swig, owner of San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel. The new landlord strove to modernize the 5-storey hotel. Aluminum and Naugahyde replaced the oak Stickley and Limbert. Fine art, statuary, and Asian objects sold at auction at low prices. Other objects were lost, stolen, or deteriorated. The 800-piece bell collection shrunk to 500 and flight insignias dwindled to fewer than 270, down from the original 600.

We continue to look at manned flight with great wonder. Throughout the world air shows attract spectators in the thousands. The shows at March Air Reserve Base, first introduced during Hap Arnold’s tenure as base commander, remain as popular as ever. Riverside and the surrounding cities work hard to ensure the viability one of the country’s oldest airbases. On a national level, the Experimental Aircraft Association hosts the annual EAA AirVenture Oshkosh drawing an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 aircraft and 700,000 visitors to Wisconsin’s Fox River Valley. Over 300 museums in US and Canada are devoted to aviation or have significant aviation related materials in their collections. Vermont and West Virginia are the two holdouts. Within a 60-mile radius of Riverside are four air museums: Murrieta’s Wings and Rotors Museum, the Chino Hall of Fame Plane Museum, the Palm Springs Air Museum, and March Field Air Museum. At the Mission Inn, the ownership continues to honor aviators at the Famous Fliers’ Wall. Reproductions of the Saint Francis good-luck pieces sell in the museum store, along with Walt Park’s Fliers’ Wall history. Although not an air museum or a California mission, Frank Miller’s Glenwood retains a fascinating piece of aviation history. Perhaps this fascination with flight was “in the cards” all along. The Glenwood Mission Inn opened in 1903, the same year Orrville and Wilbur Wright’s flights at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina captivated a public emerging from the Victorian era.

Endnotes

Friends of the Mission Inn Scrapbook 1. IV-5 (no title or publication given, circa 1968-1975) Riverside Local History Resource Center, Riverside Public Library, Riverside, California.

Allis Hutchings to Reginald Orcutt, 17 February 1934, 1. LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder I. Archives. Mission Inn Foundation and Museum. Riverside, California.

Photocopy Women’s International Association of Aeronautics stationary. LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder IV. Archives. Mission Inn Foundation and Museum. Riverside, California. Allis Hutchings served as the Secretary of the organization. Other officers included President – Lady Hay Drummond-Hay and Mrs. Ulysses Grant McQueen, Founder and Honorary President.

Joseph J. Corn. The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002), 30.

“Aim to Teach Boys How to be Fliers,” The New York Times, 15 May 1927, 2.

“Toy Demand Shows Air-Minded Trend,” The New York Times, 20 December 1929, 37.

Corn, The Winged Gospel, 90.

Eunice Fuller Barnard, “Our Soldiers to Live in Model Towns,” The New York Times, 7 April 1929, SM6.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Materials for March Field, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Historic Overview Section 8, page 37, n.d.

“Riverside Family on Long Air Trip to South America,” Riverside Daily Press, 11 December 1936.

“The Air Ways,” So Your Going, February 1937, 8.

Allis Hutchings to Reginald Orcutt, 17 February 1934, 1.

Handbook of the Mission Inn (1951), 56. This poem was inscribed on a watercolor of St. Francis on display in the chapel by artist Fanny Warren.

DeWitt Hutchings to Lt. Col. H. G. Reeder, 11 February 1947, LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder VII. Archives. Mission Inn Foundation and Museum. Riverside, California.

From the poem The Sermon of St. Francis by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst.

DeWitt Hutchings to David L. Behncke, 17 July 1948, LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder I. Archives. Mission Inn Foundation and Museum. Riverside, California.

Allis Hutchings to Reginald Orcutt, 17 February 1934, 1.

Erick Hildesheim to DeWitt Hutchings, 18 May 1948, LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder I Archives. Mission Inn Foundation and Museum. Riverside, California.

“Lady Hay Drummond Hay, Noted Aviator, Guest at Inn,” Riverside Daily Press, 19 May 1936.

Lady Drummond Hay, “Eckener to Shift Hindenburg Route,” The New York Times, 10 May 1936, 35.

http://tycho.usno.navy.mil/vphase.html

“Titled Journalist Greeted: Lady Drummond-Hay Flying Writer,” Los Angeles Times, 19 May 1936, A1.

“Hutchings Recalls Trip on Ill-Fated Hindenburg,” Riverside Daily Press, 10 May 1937.

“Hutchings Recalls Trip on Ill-Fated Hindenburg,” Riverside Daily Press, 10 May 1937.

DeWitt Hutchings to David L. Behncke, 17 July 1948. LH/Mission Inn/Collections/Military Insignia/ Folder I.

Civil Air Patrol, Your Aerospace World (Maxwell AFB: National Headquarters Civil Air Patrol, n.d.), 1-14.

Robert D. Campbell, Reminiscences of a Birdman (Uxbridge, MA: Living History Press LLC, 2009), 167-168.

Adelaide Ovington, An Aviator’s Wife (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1920), 39.

“Earle Ovington All set for ‘Crime’ in Air War,” Los Angeles Times, 12 July 1932, 10.

Selected Bibliography

Archbold, Rick. (1994). Hindenburg: An Illustrated History. New York: Madison Press/Warner.

Campbell, Robert D. (2009). Reminiscences of a Birdman. Uxbridge, MA: Living History Press, LLC.

Corn, Joseph J. (1983). The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation, 1900-1950. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dick, Harold G. and Douglas Hill Robinson. (1991). The Golden Age of Great Passenger Ships: Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Klotz, Esther. (1982). The Mission Inn: Its History and Artifacts. Riverside, CA: Rubidoux Printing.

Ovington, Adelaide. (1920). An Aviator’s Wife. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company.

Parks, Walter P. (1986). The Famous Fliers’ Wall of the Mission Inn. Orange, California: Infinity Press, Rubidoux, California.

Robinson, Douglas Hill. (1979). Giants in the Sky: A History of the Rigid Airship

3rd edition: Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Roessler, Walter and Leo Gomez. (1997). Amelia Earhart – Case Closed? Hummelstown, PA: Markowski International Publishers.

Tanaka, Shelly. (1993). Disaster of the Hindenburg: the Last Flight of the Greatest Airship Ever Built. New York: Scholastic/Madison Press.

http://www.centennialofflight.gov

http://www.airmailpioneers.org/history/milestone3.html

|