|

Meeting Number 1721

4:00 P.M.

December 1, 2005

“The Other Yosemite”

Boyd A. Nies, M. D.

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library

THE OTHER YOSEMITE

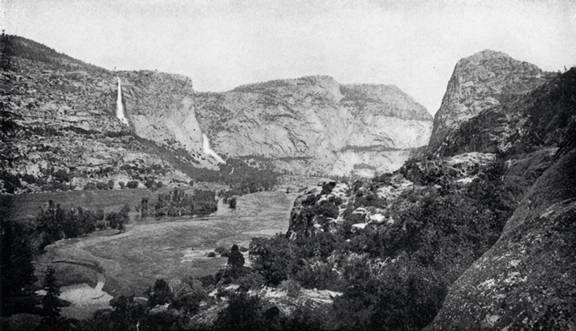

Yosemite Valley is famous as one of the most beautiful sites in the world. It could also be thought of as a symbol of California. The recently issued California quarter pictures Yosemite Valley, along with John Muir and the California condor. Less well known is another similar valley in Yosemite National Park: Hetch Hetchy.

Hetch Hetchy is situated in the northwest corner of Yosemite National Park along the course of the Tuolumne River. In a 1907 letter from the archives of the A. K. Smiley Public Library, John Muir wrote: “The Hetch Hetchy I have always called ‘The Tuolumne Yosemite’, for it is a wonderfully exact counterpart of the greater valley, not only in its sublime rocks and waterfalls but in the gardens, groves and meadows of its park-like floor.”

There are at least two accounts of the origin of the unusual name of the valley. One attributes its name to the Indian word “hatchatchie”, meaning a type of grass growing in the valley. A second refers to an Indian word “hetchy”, meaning tree. Originally, there were said to have been two yellow pine trees at the end of the valley; Hetch Hetchy, in this interpretation is thought to mean “The Valley of Two Trees”.

Both Yosemite Valley and Hetch Hetchy were carved by glaciers. The major period of glacial activity excavating and shaping the valleys was the Sherwin glaciation, which is thought to have lasted 300,000 years and to have ended about 1,000,000 years ago. Subsequent glaciers did not fill Yosemite Valley completely. Thus, over that approximately million year interval, erosive forces produced the pinnacles and spires that characterize the walls of Yosemite Valley. In contrast, Hetch Hetchy was filled to the rim by the Tioga glacier, which peaked about 20,000 years ago. The lack of time for extensive erosion accounts for the relatively smooth walls of Hetch Hetchy. Hetch Hetchy Valley (1,730 acres) is about one half the size of Yosemite Valley (3,509 acres). Both valleys are 6.8 miles long, but Hetch Hetchy Valley is only half as wide as Yosemite Valley. (Figures 1-6).

The gold rush of 1849 first brought white men into the Yosemite area. Yosemite Valley was probably first seen by non natives in 1849, Hetch Hetchy in 1850. Yosemite Valley was first explored in detail in 1851 by the Mariposa Battalion, a voluntary militia formed to capture Yosemite Indians who had raided prospectors in the area. (Lafayette Bunnell, a member of the battalion whose description of the valley is inscribed on a plaque at the tunnel view parking lot, is an ancestor of Redlander Dr. William Bunnell.) Hetch Hetchy was not initially explored in as much detail.

Over the next decade, an ever increasing stream of journalists, artists, entrepreneurs, and tourists made the arduous journey to Yosemite and the Big Tree area. By 1860, hotels were available for visitors to Yosemite Valley. Hetch Hetchy was largely ignored.

Prior to the mid nineteenth century, conquering the wilderness was the first priority for Americans. By the 1850’s, however, writings by Marsh, Thoreau, and others had fostered the concept that certain areas should be preserved from development. In 1864, Congress passed and President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act. This Act granted to the State of California Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove with the stipulation “that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation …for all time”. The Yosemite Grant was officially validated by the California State Legislature in 1866. This Grant set the precedent for the preservation of particularly scenic areas by the federal government, leading to the establishment of Yellowstone as the first national park in 1872.

Administration of the Grant by a Board of Commissioners was difficult primarily because of a lack of adequate state funding. This resulted in the establishment of multiple commercial enterprises in the valley as a source of income. There was also inadequate enforcement, resulting in the depletion of the native game due to poaching and also to problems with grazing and lumbering in adjacent areas. These conditions led to the U.S. Cavalry being assigned to the area in 1886 to restore order. There were also calls for expansion of the Yosemite reserve. The preservationists under the leadership of John Muir were eventually successful, when, in 1890, President Harrison signed the bill creating the nation’s second national park comprising nearly one million acres surrounding Yosemite Valley, including Hetch Hetchy. This act, however, did not affect Yosemite Valley and the Big Tree Grove, both of which remained under the control of the State of California.

By the time that Yosemite National Park was established in 1890, San Francisco had long since become the leading city in California. What had been a small settlement in 1848 became a boomtown in 1849 with the discovery of gold in the Sierra. By 1890, San Francisco’s population was nearly 300,000, Los Angeles’ only 50,000. With the growth of the city, there was an increasing problem of providing an adequate supply of water. After local supplies became inadequate, water was shipped across the bay on barges. Subsequently, sources on the peninsula were tapped. Eventually, one water company emerged as the primary supplier of water to the city: the Spring Valley Water Company. The relationship between the city and the water company was frequently a contentious one. There were complaints of poor service and high prices. Several attempts by the city to buy Spring Valley were unsuccessful due to an excessive asking price by the water company and also to bribery of civic officials. In the 1880’s San Francisco began looking for an alternate water source. Since local and regional water sources had already been exploited, the possibility of bringing water from the Sierra began to be explored.

In 1896, James Duval Phelan was elected mayor of San Francisco. He had a dream of making San Francisco one of the great cities of the world. The essentials of his program to accomplish this dream were eliminating graft and corruption, initiating systematic civic planning, fostering cultural institutions and civic pride, and developing a public water supply. In 1900, at the direction of the Board of Supervisors, the city engineer, Carl Grunsky, produced a report evaluating several potential water sources in the Sierra. This report concluded that the Tuolumne River in the Hetch Hetchy area was the preferred source.

The fact that Hetch Hetchy and nearby Lake Eleanor were in a national park apparently negated their development as a water source for San Francisco. However, in 1901, Congress passed the Right of Way Act, which authorized rights of ways on public lands, among other things, for electrical plants, power lines, dams, and water conduits upon the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. This apparent loophole energized Phelan to secretly file for water rights in the Hetch Hetchy area under his own name and then in 1902 to petition Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Hitchcock, for permission to proceed with the project. Three times from 1903 to 1906, the petition was denied by Hitchcock. By early 1906, both the California Legislature and the United States Congress had approved the recession of the Yosemite Grant to the federal government. At that point the Hetch Hetchy project appeared dead. Then in April 1906, the great San Francisco earthquake occurred followed by a disastrous fire. The main reservoir for San Francisco, the Crystal Springs Reservoir, survived intact, but the earthquake damaged many of the pipes leading to the city, resulting in insufficient water available for fighting the fires. Despite the fact that no water supply system available in 1906 could have withstood the force of the earthquake, public support for a municipal water system was rekindled.

In 1907, Secretary Hitchcock resigned and was replaced by James Garfield. After a series of meetings, Secretary Garfield, in 1908, granted the permit to proceed with the project, with stipulations that Lake Eleanor be developed first, that the water rights of the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts be preserved, that the city sell any excess electric power to the irrigation districts, and that the city surrender to the federal government land outside the national park in trade for the reservoir sites. The last mentioned stipulation proved to be a particularly important one, since the proposed exchange of lands led to congressional hearings.

Thus began a national debate over the fate of Hetch Hetchy, triggered by the congressional hearings of December 1908 and January 1909. On one side were the progressives led by Phelan, Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the U. S. Forest Service, San Francisco city engineer Marsden Manson, and others. On the other side were the preservationists, who for the first time had a unified national voice. They were led by John Muir, Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century, the leading literary magazine of the time, William Colby, an attorney and longtime secretary of the Sierra Club, and others. Both groups believed that particularly scenic areas should be set aside under federal protection, free from unregulated private development. The progressives, however, believed that public lands should be used for the greatest good for the greatest number of people, which in this case meant developing a public water supply for San Francisco. They pointed out that the preservation of the valley would, in effect, allow the continuation of the private monopolies enjoyed by Spring Valley and Pacific Gas and Electric. The preservations felt strongly that a dam should not be built in a national park, although they did believe that some development for visitors would be appropriate. John Muir, in his 1912 book The Yosemite wrote: “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

The controversy continued during the presidency of William Howard Taft who was inaugurated in March 1909. Taft preferred private resource development and also had legal concerns about allowing dams in national parks. During his presidency the permit for the Hetch Hetchy project was neither revoked nor affirmed. The final decision was left to the next administration.

During the election of 1912 the Republicans were divided when Theodore Roosevelt, unable to defeat Taft for the Republican Party nomination, formed the “Bull Moose” Party. This split resulted in the election of the Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, who assumed office in March 1913. In the meantime, San Francisco had commissioned a detailed study of possible water sources for the city by an authority on hydraulic and seismic engineering, John Riley Freeman. This report not only recommended the Tuolumne River as the preferred source, but also that Hetch Hetchy and Lake Eleanor be developed simultaneously. The conclusions of the report were largely supported by a commission of army engineers.

The new Wilson administration was more favorably inclined toward the project. In April 1913, California congressman John Raker introduced the bill authorizing the Hetch Hetchy project. The House of Representatives approved the revised bill on September 3. After an extensive debate, the Senate followed suit on December 6 and President Wilson subsequently signed the bill. The Raker Act did preserve the existing water rights of the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts. It also had a provision that electric power produced by the project in excess of the needs of San Francisco could not be sold to a private entity.

The Hetch Hetchy project was one of the largest construction projects of its time, involving dams, reservoirs, conduits, powerhouses, and an aqueduct stretching 150 miles. Before construction of the dam could be started, a 68 mile long railway, a sawmill, and a powerhouse were built. The O’Shaughnessy Dam, named after the supervising engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy, was built between 1919 and 1923. Between 1923 and 1932, pipelines were laid across the central valley and the San Francisco Bay. This part of the project involved the construction of tunnels beneath the foothills and the coast range. In 1930, San Francisco purchased the Spring Valley Water Company including its distribution system. The entire project was completed and dedicated in 1934. The system was engineered to deliver water entirely by gravity. Even today, the water does not require filtration. The cost of the project was more than a hundred million dollars, paid for by the taxpayers of San Francisco. The city, however, still pays the federal government only $30,000 per year for its use of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. San Francisco does contribute $2.5 million to Yosemite National Park which funds three rangers, trail maintenance, watershed protection, and special projects, most of which help to maintain the reservoir water’s purity.

Over the years there has been expansion of the Hetch Hetchy project. The O’Shaughnessy Dam was raised in 1938 resulting in an increase in its capacity to the current level of 360,360 acre feet. (One acre foot equals 325,851 gallons.). Subsequently, additional pipelines, dams, and powerhouses have been built. Downstream on the Tuolumne River, the Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts constructed the original Don Pedro Dam in 1923. Then in 1971, they built the New Don Pedro Dam, its resulting reservoir having a storage capacity of approximately six times that of Hetch Hetchy.

Today, the water service area, in addition to San Francisco, includes San Mateo County, and portions of Santa Clara County and Alameda County. Hetch Hetchy supplies 220 million gallons of water daily to about 2.4 million people in the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as generating 1.7 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually. In San Francisco, Hetch Hetchy supplies 85% of the water and about 16% of the electricity. In contradistinction to its municipal water system, San Francisco never did develop a municipal power system. While city departments, the municipal railway, and the airport are directly supplied by Hetch Hetchy power, the citizens of San Francisco still must rely on PG &E to supply their electrical needs. Several bond issues to establish a municipal power system have failed over the years. Although the sale of power to private entities was prohibited by the Raker Act, San Francisco continued to sell power to PG & E until the Supreme Court upheld that provision of the Raker Act in 1940. Currently, the City sells excess power to the Irrigation Districts, often earning millions of dollars a year.

The O’Shaughnessy Dam and the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir can be reached by a road which intersects highway 120 near the eastern edge of Yosemite National Park. Hetch Hetchy attracts only about 50,000 visitors yearly, whereas Yosemite Valley attracts about 3.4 million. Boating, swimming, and even wading are prohibited at Hetch Hetchy and the road leading to the reservoir is closed at dark. There is a small backpackers’ campground with 19 spaces, picnic tables, and bear lockers. Hiking, backpacking, and fishing from the shore are the only permitted uses. (Figures 7-10).

The passage of the Raker Act was a bitter defeat for the environmental community. However, their leaders continued to meet on a regular basis to coordinate efforts to establish a national park system under the jurisdiction of a single agency to ensure that the parks and national monuments would be used for scenery and recreation only and not for multiple resource use. They were joined by some who had previously supported the Raker Act but later had second thoughts about the Hetch Hetchy project. The preservationists’ efforts were successful when in 1916, the Organic Act establishing the National Park Service became law.

There was relatively little public interest in Hetch Hetchy until 1987, when Donald Hodel, Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, proposed dismantling the O’Shaughnessy Dam and restoring the valley. Hodel asked the Bureau of Reclamation to do a study to determine if adequate water could be supplied to San Francisco if the dam were removed. The Bureau indicated that enough water would be available if certain modifications to the system were made. Subsequently, scientists of the U. S. Fish and Game Service, the California Department of Fish and Game, and the National Park Service did a cooperative study of the effects of dam removal. Their major conclusions were: 1) the 118 feet of the dam beneath the riverbed should remain; otherwise rapid erosion of the meadows below the previous dam site would occur; 2) sediment behind the dam would probably be only an inch or two thick, and thus would not be a major problem; 3) the river channel would likely remain; 4) there would be two options for plant life recovery: either let nature take its course or manage plant and tree recovery; the later option would ensure that native plants and trees would repopulate the valley: 5) the “bathtub ring” caused by the killing of the native lichen by the impounded water would recover in 80 to 120 years; and 6) wildlife would return rapidly. The then mayor of San Francisco, Diane Feinstein, felt strongly that further consideration of the proposal to dismantle the dam was not indicated and subsequently Congress refused to appropriate any money for further studies.

Public interest again lagged until the last few years. In 2000, the non-profit organization Restore Hetch Hetchy was formed. In 2001, University of California, Davis Professors Richard Howitt and Jay Lund developed a computer program known as the California Value Integrated Network (“CALVIN”) to predict how variables would affect water systems. In 2003, Sarah Null in her Master’s thesis at UC Davis used the CALVIN program to study the water supply implications of removing the O’Shaughnessy Dam. She concluded that water scarcity would not necessarily increase if the dam were removed. She recommended linking the New Don Pedro Reservoir to the Hetch Hetchy pipeline, but did note that if that were to be the case, hydroelectric power generation would decline and that filtration of the water delivered to San Francisco would be required. The national non-profit organization Environmental Defense also studied the effects of dam removal. They concluded that water now stored in Hetch Hetchy could be stored in the Don Pedro Reservoir and other sites and also suggested increased groundwater banking.

In August 2004, the Sacramento Bee newspaper began a series of articles and editorials on Hetch Hetchy, the editorials supporting dismantling the dam and restoring the valley. Tom Philp, associate editor of the Bee’s editorial board, subsequently received the Pultizer Prize for editorial writing. In September 2004, two members of the California Assembly, Joe Canciamilla (D-Pittsburg) and Lois Wolk (D-Davis) wrote to Governor Schwarzenegger requesting that the State review the implications of restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley. Mike Chrisman, Secretary for Resources, responded in December 2004, indicating that state agencies would analyze previous studies and would also work with the National Park Service to determine a value for a restored Hetch Hetchy Valley. Completion of that report is expected in the next few months. In July 2005, the Schwarzenegger administration conducted a public workshop on Hetch Hetchy.

Restore Hetch Hetchy released a detailed 96 page feasibility study in October 2005. Assuming that the dam is removed, this report suggests diverting Tuolumne River water just downstream from Hetch Hetchy Valley into the Canyon Tunnel of the San Francisco system and also diverting Cherry Creek into the Mountain Tunnel. Pumping stations would be needed to deliver water into the tunnels. These measures would recapture almost all of the water formerly stored in Hetch Hetchy and would also recover much, but not all, of the lost energy production. The Don Pedro Dam could be raised to provide increased storage space. Currently the Tuolumne River above the dam is a component of the National Wild and Scenic River System. Increasing the level of the reservoir would wipe out about seven tenths of a mile of the that part of the river, but an additional eight miles would be added by removing the O’Shaughnessy Dam. The Calaveras Reservoir, also a part of the San Francisco water system, could be enlarged. Many other options for ensuring an adequate supply of water and electricity for the San Francisco area were also discussed in this study. (Figure 11).

The study also provides a detailed plan for active restoration of the valley after water is drained from the reservoir. An area where aggregate was mined for the concrete for the dam construction would be restored, with removal of mining spoils and addition of topsoil. The river banks would be stabilized. Native plant and tree seeds would be collected five years before the dam was to be removed and propagated. Aggressive replanting of these native grasses, plants, and trees would take place as soon as the soil had dried sufficiently. Non-native plants would be suppressed.

After restoration Restore Hetch Hetchy envisions a valley free of commercial establishments such as hotels, stores, and restaurants. Such visitor facilities could be expanded in areas just outside the park and possibly also on the natural bench above the current reservoir, where San Francisco currently has facilities. Hiking trails and possibly more formal trails for wheelchairs and bicycles would be allowed. Campgrounds on the valley floor would be considered if the river water purity could be assured. Fishing in the river, rafting, kayaking, and possibly hang gliding would be allowed.

Restore Hetch Hetchy also believes that there would be associated significant economic benefits from valley restoration. An increase of $60 million dollars in spending generated by Yosemite National Park is projected when Hetch Hetchy becomes a significant visitor destination. Increased travel and tourism would be expected to benefit the gateway communities. An estimated 500 jobs would be created during the period of dam removal.

The feasibility study estimates that the total cost of removing the dam, restoring the valley, adding a filtration system, and replacing the water and power previously supplied by the Hetch Hetchy reservoir would be about one billion dollars. Sources of funding would likely be a combination of private, state, and federal money.

San Francisco’s civic leaders, although interested in the ongoing studies of Hetch Hetchy, have urged extreme caution in actually considering removal of the dam. Susan Leal, general manager of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, has been a particularly vehement opponent of valley restoration, calling the plan foolhardy. In a recent Commonwealth Club panel on Hetch Hetchy, Ms. Leal stated that her agency’s cost estimate for valley restoration, including creating alternative water storage and power generation facilities would be $10 to $15 billion dollars. There are also the matters of civic tradition and pride. Kevin Starr, the State Librarian emeritus and currently University Professor of History at USC has said: “For multi generational San Franciscans, such as myself, the Hetch Hetchy is part of the DNA code of San Francisco. It is one of the foundations upon which the greatness of the city rests – that to comprehend disestablishing it, tearing it down, going somewhere else, is almost to think the unthinkable.” Allen Short, general manager of the Modesto Irrigation District, has recently indicated that water in the Don Pedro reservoir is for the use of the Irrigation Districts only, and that a replacement reservoir must be in place before the O’Shaughnessy Dam is demolished.

State laws passed in 2002 have mandated that the Hetch Hetchy water system be rebuilt to better withstand a large earthquake. A $1.6 billion bond issue was passed by the voters of San Francisco in the fall of 2002 to retro-fit and upgrade the system. The other water districts receiving Hetch Hetchy water have pledged at least an additional $2 billion dollars for the upgrade. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission’s Water System Improvement Program (WSIP) also includes plans for expanding the system capacity by building a fourth pipeline and enlarging the Calaveras Reservoir, thereby allowing increased extraction of water from the Tuolumne River. Meetings to elicit public comment on the WISP proposal are planned.

It has now been about 100 years since Hetch Hetchy first became the subject of public debate. San Francisco and the progressives eventually prevailed in that initial controversy and the O’Shaughnessy Dam was built. Today the debate pits San Francisco and its allies who wish to maintain the dam and the Hetch Hetchy reservoir against environmental organizations which wish to tear down the dam and restore the valley. What will the outcome be this time?

|