|

4:00 P.M.

February 16, 2006

Meeting Number 1726

"The Virtue of Courage"

John Morton Jones

Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library

Summary

Courage, chief among the cardinal virtues, has an elusive quality and shines in many hues, but doing a worthy deed in the face of mortal fear has been its hallmark since the beginning of recorded history. Examples abound from battlefield valor to the risk of a vessel’s foundering on the rocks of a lee shore and from Socrates to John Wayne we hear of its allure.

KEY WORDS

Courage

Flight 93

Heavy weather sailing

William Ian Miller, Professor of Law, author

The Mystery Of Courage, Harvard University Press, ©. 2000

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION

In memory of my wiry boyhood friend Dan Sheehan who too many times shamed me to be his fearful sparing partner in a sandlot boxing ring. My thanks go to Professor William Ian Miller, now of my old law school, who inspired this paper with his book The Mystery Of Courage and to my loving daughter, Molly McCormick, who unlocked cryptic doors to the www and to her ever patient husband Steve.

BACKGROUND OF THE AUTHOR

“Mort” Jones has been a Redlander for 30 years. His hometown is Danville, Illinois. At 17 he joined the Navy and after two years matriculated to the University of Michigan where he earned his undergraduate and law degrees. Thereafter he practiced law in Illinois and held a number of public offices. In 1970 he became a Hearing Officer for the Illinois Director Of Labor and that led to his present appointment as a California Administrative Law Judge, dealing generally with cases involving Labor and Employment Law. He is admitted to the Bar in both California and Illinois.

Jones is a member of the Forum and Torch Clubs in Redlands as well as the Fortnightly Club. As a Past Commander, he is a life member of the American Legion. He and his wife Betty have 4 grown children and 11 grandchildren. For many years Betty and Mort have spent their vacations on islands off the coast of Maine.

THE VIRTUE OF COURAGE

In 480 B. C. the king of Sparta, Leonides, with 300 faithful men at his side, held the narrow mountain pass at Thermopylae against the invading hordes of Xerxes. Outnumbered 50-1 in that bloody crevice, the Spartans fought the Persians hand to hand with their swords and spears for two long days until Leonides and all his brave company were cut down. All except Pantites, who ran to Sparta with the news.

King Leonides had ordered Pantites to go, but Pantites, having obeyed, was so ashamed he had missed the end of the battle and death with honor, shoulder to shoulder with his compatriots, killed himself.

The news of the sacrificial stand at Thermopylae spread quickly over all of Greece; the people were aroused to unite against the Persians, and Xerxes was soon forced to withdraw from their land.

Thus is courage enthroned as a virtue by the earliest histories.

Two thousand years after Thermopylae, Miguel de Cervantes would write, “He who loses wealth, loses much, he who loses a friend loses more, but he who loses his courage loses all.”

Cervantes could speak from experience. He only began to write his masterpiece, Don Quixote, when he was 58 years old, but prior to that he had fought as a soldier in five major battles in Italy and North Africa; his left hand had been maimed at Lepanto; he had endured capture and five long years of imprisonment by Algerian pirates.

The earliest discussions of courage place it first among the four cardinal virtues which also include prudence, justice and temperance. Not only in the narrow sense of a willingness to face death to win the good fight, but acts of courage secure the space where the other virtues can develop. More broadly, courage can now be construed with fortitude as its base; the firmness and dedication to defend and protect the more tranquil virtues. Clare Boothe Luce wrote that “Courage is the ladder on which all the other virtues mount.” And Samuel Johnson saw courage as the “greatest of all virtues; because, unless a man has that virtue, he has no security for preserving any other.”

That said, the psychological of courage is elusive. Plato gave these words to the interlocutor Laches: “For I fancy that I do know the nature of courage; but, somehow or other, she has slipped away from me, and I can not get hold of her or tell her nature.” Laches would agree, however, that there is a courage of dishing it out and a courage of taking it. It is surely the stuff of good stories.

Here in southern California some 20 years ago our tranquil coast was struck by a particularly severe winter storm. Just after dark on a Friday night it hit the beaches of Orange County with driving rain, high seas, and hurricane-force winds. Its crashing waves took out the Seal Beach pier. And that night I was one of seven crewmembers on a 43-foot sailing yacht caught in Cat Harbor on the far side of Catalina Island. The open ocean side.

We were one of a fleet of six boats, the best vessels in the Newport Sailing Club. We had set out that morning for a long-planned weekend sail which would include a circumnavigation of San Clemente Island, off San Diego. As we left Newport Harbor, the storm was brewing, the sea was roughing up, but we expected nothing more than a fast and probably a wet sail. And we reached the outer waters of Avalon, running at hull speed, in record time.

In charge of the fleet on the lead boat was Ian Bruce. Ian was an old salt, and graduate of years of commercial sailing in the Baltic Sea. The skipper of the yawl on which I was assigned was an experienced sailor named Tom (I’ll call him). Tom was young and still tanned from a summer of blue water cruising. The skippers kept in touch with each other by short wave radio.

Ian, the commandant, chose to by-pass Avalon Harbor and to head the fleet south toward San Clemente Island, according to the original plans. But we, that is, the six boats, no sooner cleared the south end of Catalina Island than the wind increased and the clouds on the horizon blackened. Ian thereupon radioed that we would seek refuge in little Cat Harbor. Thus we turned and sped north before the wind running parallel with the breakers on the Catalina shore. And into Cat we coasted, searching out the few mooring wands which marked, like fishing bobbers, great concrete blocks on the harbor floor. We would secure our boats on those heavy moorings. And we dropped our bow anchors too as a safety measure in case a mooring chain or hawser should part. The blackness of night came early and the wind rose to a roar. And, unexpectedly, it shifted from south east to south west. That shift turned our “refuge” into a veritable wind tunnel. Escape was impossible. And the lee shore was a massive wall of jagged rocks.

When the wind reached hurricane force and with the rain stinging our face and hands, big trouble developed. The high-sided yacht on our port quarter suffered a severe knockdown and then the boat immediately astern began to drag its mooring. It was apparent she had not dropped her anchor and for some unknown reason was unable to. Ian, the commandant, who was moored closest to the harbor mouth, ahead of us, started his diesel, threw off his mooring line and headed to the distressed boat to help its crew. With our hand-held spotlights we watched the two boats raft up and quite soon the missing bow anchor was found and dropped. Then Ian was in distress. His diesel lacked the power to overcome the headwind he faced to return to his mooring. He was laboring forward and making no headway at all just off our stern. So Tom, our skipper, paid out our mooring line and with grappling hooks and lines thrown out against the gale we secured Ian’s hull next to ours and pulled him safely to our own mooring. In the roar and the shaking and pitching and pulling of those moments I remember only screams and screams and screams of fright and anguish from a young woman who was on Ian’s boat.

Now it was obvious our mooring could not hold two boats. So Tom, our skipper, without a moment of indecision, chose to leave. He had seen one lone unclaimed mooring wand back in the dead end of the harbor, perhaps ten boat lengths downwind. Tom clambered to the bow, unshackled our mooring line and started to weigh our bow anchor. But it was fowled, caught on a snag on the harbor bottom. Out whipped Tom’s knife. He chopped off our anchor line and the wind immediately carried us – oh so fast! – back into the raging tunnel – to that last mooring in front of the rocks. And from that mooring we safely bounced through the night. When morning dawned we found Ian’s starboard running light rolling around in our cockpit.

Tom’s act of giving Ian our mooring that night, risking so much between the face of a terrible wind and the sharp boulders on the shore exemplified courage. Danger loomed. Tom acted.

Just what constitutes courage? It is an elusive virtue. The horrific events of 9-11 gave new life to the word but its overuse tended to melt away its impact, its distinction. We must ask, were all the firefighters “courageous” as they ran into the Twin Towers according to drill and experience with high-rise fires?

Courage can be misunderstood. Marlon Brando once snapped, “the only reason I’m in Hollywood is that I don’t have the moral courage to refuse the money.” And Andrew Wyeth declined to attend a special showing of his works in Atlanta because “I don’t have the courage to see how the exhibition is arranged.”

Courage involves more than mere grit or nerve. Surely it’s no joke. Courage involves an intrepidity mixed with bravery, tenacity; courage is a confrontation of danger, usually a bold and skillful stroke, a taking the bull by the horns.

I have my own definition of courage. It is this: Courage is the determination to carry out a fearsome and worthy duty accepted; it is the performance of that act despite the natural and almost overwhelming urge to abandon the cause.

The presence of fear is an integral part of any act of courage. The courageous must overcome that fear. The fear must be rational. The foreseeable consequences of failure must be deadly, at least in a figurative sense. Mark Twain explained, “Courage is the resistance to fear, mastery of fear, not the absence of fear.” And wasn’t this typical of John Wayne when he said “courage is being scared to death and saddling up anyway.”

The ancient Vikings and the early Celts were ferocious warriors, but their crude culture bred heartless behavior and rashness; they exhibited a berserk instinct so overwhelming that fear played no part in their lives. As a result, most historians attribute the Viking raids and Celtic aggressions not as courageous acts, but simply as brutish. Compare the civilized and hopeful encouragement of Martin Luther King: “We must build dikes of courage to hold back the flood of fear.”

Eddie Rickenbacker put it simply, “Courage is doing what you’re afraid to do. There can be no courage unless you’re scared.”

Harry Truman put a twist on the concept of accomplishment in the face of danger everywhere: “America was not built on fear. America was built on courage and on unbeatable determination to do the job at hand.”

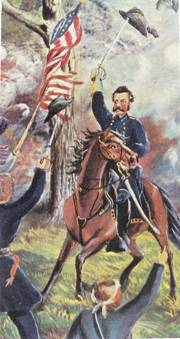

On July 3, 1863 at Gettysburg the “Job at hand” for General Pickett was to take the heights of Cemetery Ridge; to crack the Union Center. So his fresh division of 15 thousand, led by Brigadier General Lewis Armistead, attacked that fateful afternoon. Before they burst forward out of the woods and on to the plain which would be soaked in blood, Armistead called out to his men, “Trust in God and fear nothing!”

And then Armistead truly led his division. He stepped out first and stayed in front of the waves of his foot soldiers with his plumed hat held high above his head on the tip of his raised sword so his men could take courage to follow him. Armistead thus charged through the storm of bullets and cannon shot and smoke until he was mortally shot down just as he reached the Union line. I won’t judge the “courage” of Armistead’s troops, but I point to his selfless act of calling fire upon himself as an example of true physical courage.

Some analysts of the virtue of courage emphasize the “disposition” of the actor as a critical ingredient. But it is not the intention or attitude of the actor which is important, nor is it his forming a judgment about the worthiness of the goal. It is, rather, the doing of the deed.

In Vietnam, a medic knicknamed “Doc” was attached to his company of infantry, according to Tim O’Brien, the author of a memoir of that war. Doc never flinched when and where he was needed, no matter the intensity of the firefight. O’Brien had seen Doc run from his foxhole, through enemy fire, to “wrap useless cloth around a dieing soldier’s chest.” And Doc explained, “When someone hollers for a medic, if you’re the medic, you run toward the shout.” O’Brien decided Doc was incapable of possessing courage because he didn’t seem capable of fear. But was Doc too dim to be courageous or was he merely being modest, as many true heroes are? To say “I just reacted” is the language of modesty, not stupidity. Bottom line: a medic like Doc shows us courage.

My brother-in-law Frank Keith joined the Marines in early 1940 and not long after Pearl Harbor was given a battlefield commission. He led his company across the beach and into the jungles of Saipan. With 43 thousand Japanese troops well fortified on the island, that “stepping stone” in the Pacific proved to be a hard nut to crack. But like Guadalcanal and Tarawa and Iwo Jima, we cracked it alright and then, on Saipan, the enemy dead were counted. There were 42 thousand bodies. Many were suicides, but the awful fact remained: more than 95% of the Japanese defenders had chosen death rather than the disgrace of capture. It is an example of the maxim; “Death before dishonor.” Like the Spartan Pantites, the messenger from Thermopylae, who was shamed because he had survived, the warrior culture dictated death by whatever means. But cultural mandate or no, courage, expressing its horrid face, cursed the island of Saipan.

Flash forward two generations. Peer into the cabin of a Boeing airliner. It is United Flight 93 and the passengers have been herded to the back of the plane by a hijacker who says he has a bomb. The passengers are on their cell phones and air phones. They know 3 other airliners have just been used as bombs in New York and Washington. They know their own pilot has been knifed to death and probably the co-pilot too. They know a terrorist is at the controls up in the cockpit and at least another is holding the first class passengers hostage. They realize that the plane has turned back east where the Twin Towers stood and that the Pentagon is burning. At least three of the passengers (and likely more) decide to rush the cockpit and retake the controls. If the plane is to crash, at least it will be at their hands. Maybe in a muddy field in Pennsylvania. Todd Beamer is on an air phone talking to a supervisor. Together they pray the 23rd Psalm. Todd then turns away from the telephone and says “Are you guys ready? Let’s roll!” and nothing more is heard. Socrates would agree: We know courage when we see it.

We have not looked at another sort of courage, the courage of endurance. Such courage is found in the populace of a besieged city; Leningrad comes to mind. For almost two years that city was encircled by the Germans. It was bombed and shelled and struck again and again by tanks and troops, but it was never taken. By the middle of the dreadful winter of 1941-42, between 3,500 and 4,000 people within the walls were dieing of starvation every day. By official figures altogether 630,000 men, women and children died during the blockade. That’s more than grit. The survival of Leningrad took enormous courage.

The courage of endurance is also seen in the experiences of captives: the survival over years of dreadful torments in an enemy prison by John McCain and Jeramiah Denton and hundreds of others who were captured in Vietnam. Those men will forever be honored for their stiff-necked endurance, for their courage. They held their heads high.

And we must not overlook what we now call “moral courage.” That’s the courage to stand up for what we believe is right, even though our stand is unpopular and might lead to economic ruin or the loss of friendships or even the loss of personal freedom. That is the stuff of another paper, another day.

The Bible is loaded with stories of courage. I won’t begin to list them. They have been perused and interpreted and critiqued for over 3,000 years. The story of Jesus is at the pinnacle of these. As related in the New Testament, Jesus, in his mortal humanity, chose to go to Jerusalem and there to provoke his painful death for the highest imaginable cause. As a man he showed his generation and all those generations to follow, sheer courage.

The apostles carried on, but most of them met their end under circumstances not recorded in the testament. James, called “the less” was one. He was so-called because he was shorter or younger than the other James.

Paul called James the Less the “brother of the Lord.” Perhaps he was a cousin of Jesus, since “brethren” in the ancient Near East included one’s cousins. At any rate, Hegesippus, who actually knew the apostles, is quoted by Eusebius, the first ecclesiastical historian, as saying that after the ascension of Jesus, the governance of the local Christian Community fell to the younger James, who became know as “The Just.” He lived austerely and preached so forcefully that many in Jerusalem were converted to the new faith. This, of course, caused James to suffer the hostility of those in power, particularly, the Pharisees. In the seventh year of his episcopate they saw to it that James was severely beaten. But it only seemed to invigorate him.

Six years after the beating, James was forcefully taken to the peak of the roof of the Temple and hurled to the ground. Now, lying injured and helpless, James refused to deny the divinity of Jesus. So he was stoned and finally clubbed to death. Hence it may be said that James the Just, in annals of the early Christian church unfamiliar to many, demonstrated well the courage of martyrdom.

So now these musings have run their course. As I recorded them, I tried mightily to remember an occasion, or even a moment in my life which exemplified courage of my own. I remember instances of fear (that final examination!), of anger (being taunted by an opposing guard in a football game), of brave intentions (I wanted to earn the Navy Cross in World War II, but the closest I came even to sea duty was a stint of chipping paint on a rusty seaplane tender while she was ingloriously sitting high and dry in a drydock). I remember rash acts, but none from which a worthy result would obtain. Fate never dealt me a chance to “put my life on the line.” Had such a chance been given, would I have ducked with cowardliness? I probably will never know, but Lord Moran gave the virtue a lofty definition: “Courage is a moral quality. It is not a chance gift of nature like an aptitude for games. It is a cold choice between alternatives.” I can only hope that if that cold choice is ever handed to me, I will, like Doc, the medic in the firefight, run, with bandages ready, toward the shout for help.

When I was a boy, I attended Sunday School at St. James Methodist Episcopal Church in Danville, Illinois. But I never learned which James it was for whom the church was dedicated.

|